Cathepsin K: both a likely biomarker and a new therapeutic target in lymphangioleiomyomatosis?

Abstract

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a rare disease that is characterized by cystic lung destruction and lymphangiomas and is associated with a high risk of osteoporosis-related bone fractures. Its diagnosis is based on pulmonary anatomopathological criteria combined with chest computed tomography. VEGF-D is the only serum diagnostic biomarker used in the clinic, while inhibition of the mTOR pathway by rapamycin is currently the only reference therapy for LAM. Human cathepsin K (CatK), a potent collagenase predominantly found in osteoclasts, is considered as a valuable target for anti-osteoporosis and bone cancer therapy. Recently, CatK, which is overexpressed in lung cysts, was proposed as a putative LAM biomarker. Moreover, CatK may take part in the LAM pathophysiology by participating in pulmonary cystic destruction and bone degradation. Accordingly, targeting collagenolytic activity of CatK by exosite-binding inhibitors in combination with mTOR inhibition could represent an innovative therapeutic option for reducing lung destruction in LAM.

Keywords

CATHEPSIN K: AN OVERVIEW

Introduction

Cysteine cathepsins (cathepsins B, C, F, H, K, L, O, S, V, X, and W) are a group of eleven structurally related papain-like proteases (clan CA, family C1) in humans (MEROPS database; http://merops.sanger.ac.uk). These enzymes are primarily found in acidic endosomal/lysosomal compartments where they partake in various cellular processes (i.e., non-specific intracellular protein degradation and turnover, autophagy, and immune responses)[1,2]. Cysteine cathepsins, which are expressed either ubiquitously or with tissue- and

First, we summarize contemporary knowledge of the molecular aspects of CatK (genomic organization, tissue expression, functional and structural characteristics, substrate specificity, and regulation of its activity) and review interventional strategies currently developed to selectively prevent the uncontrolled collagenolytic activity of CatK in osteoporosis and bone cancer. Then, following a concise description of lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), a rare human disease, we discuss both the interest in using CatK as a new LAM biomarker and in targeting CatK to reduce lung destruction in LAM. Indeed, given the severity of the disease and the ensuing loss of lung function that might be associated with CatK expression level in LAM, inhibition of CatK could represent an additional therapeutic option, in addition to inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway.

Cathepsin K: molecular and biological characteristics

Human CatK is encoded by a single gene [Cathepsin-K (CTSK), ~12.1 kb], localized on chromosome 1q21, such as cathepsin S (CatS)[1]. CTSK gene expression is organized and tightly controlled at multiple steps, and likely involves the interaction of several transcription factors that are activated by cytokines. For instance, interferon (IFN)-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-13 positively regulate the synthesis of CatK, while transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 and IL-10 may repress its expression level (for review:[5,11]).

CatK (EC 3.4.22.38) is a monomeric endopeptidase (~24 kDa) that shares a common papain-like structure, consisting of two globular domains folded together to form a ‘‘V’’-shaped active site cleft in the center. Although the catalytic triad Cys25, His159, Asn175 (papain numbering) is well conserved, mapping studies of the crystal structure of CatK have revealed differences in the substrate binding subsites (labeled Sn-Sn’), which are located on both sides of the substrate’s scissile bond (corresponding to the complementary positions Pn-Pn’)[12]. Notably, the residues forming the S2 binding pocket of CatK, which is the major determinant of its substrate specificity, are crucial for its preference for hydrophobic and aliphatic amino acids (for review:[5]). Both the binding pattern and substrate specificity of CatK were previously detailed by Lecaille et al.[5]. Importantly, CatK displays an unusual ability among cysteine cathepsins to accept Pro in the S2 pocket, a recognition residue of collagens. Based on these data, selective substrates and activity-based probes for CatK have been developed[13-16].

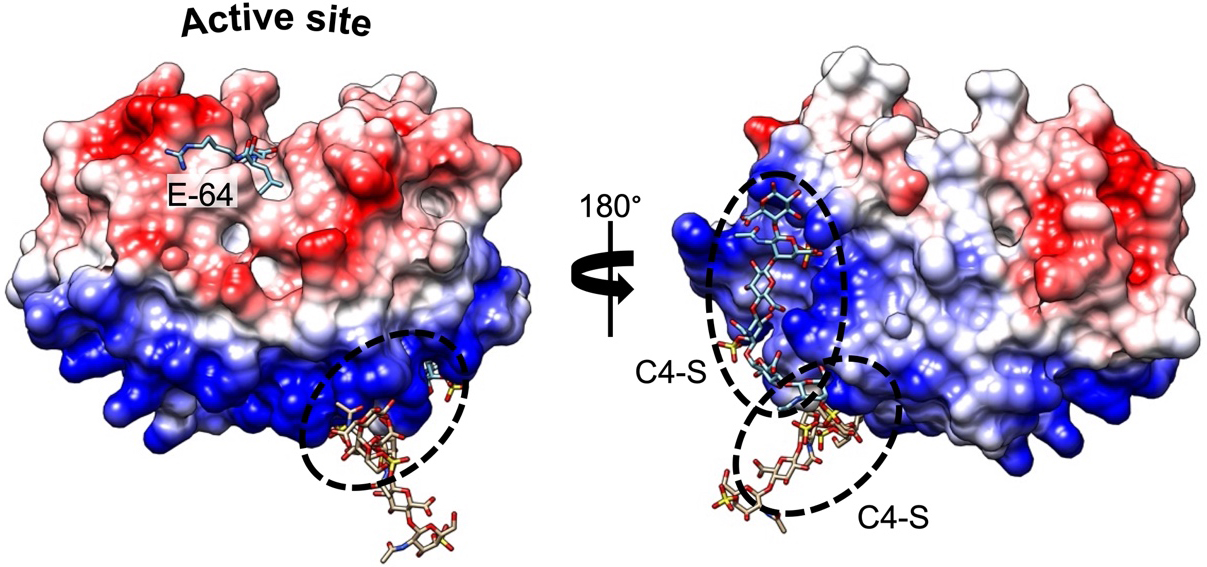

Compared with other human proteases, CatK displays a unique potency to cleave within the triple helix of type I and II collagens[17]. Furthermore, the presence of chondroitin 4-sulfate (C4-S), a glycosaminoglycan (GAG) predominantly expressed in bone and cartilage, is required to promote its collagenolytic activity by forming high molecular complexes[18]. The formation of an active complex between the negatively charged C4-S and specific positively charged residues of CatK (thereby shaping a so-called exosite located opposite the active site) is unique among human cysteine cathepsins [Figure 1]. In the absence of GAG, the ability of CatK to cleave triple helical collagen fibrils is impaired. Accordingly, it has been hypothesized that selective inhibitors able to disrupt the CatK/C4-S complex by targeting the C4-S binding exosite could inhibit its collagenase activity without impairing other regulatory peptidase and protease activities (see further section). In addition to collagens, CatK hydrolyzes other extracellular matrix (ECM) components such as elastin fibers and aggrecans[19]. CatK is a lysosomal protease that is mainly active at an acidic pH of 5.5 and rapidly inactivated at neutral pH. Nevertheless, lung macrophages and osteoclasts secrete CatK, which remains active in the pericellular space due to the presence of H+-ATPase pump or Na+/H+ exchanger[20,21]. In addition to its primary location in bone, high levels of CatK have also been detected in synovial fibroblasts, aortic smooth muscle cells, macrophages, and epithelial cells, while CatK messenger RNA (mRNA) levels increase in other tissues such as the ovary, synovia, heart, skin, and lungs following scarring or inflammation[10,22,23]. Beyond its collagenolytic activity and its involvement in ECM remodeling, CatK also contributes to the maturation of thyroid hormones by participating in the processing of thyroglobulin[24,25]. Moreover, it plays a pivotal protective role in lung homeostasis through its ability to proteolytically inactivate TGF-β1[26,27]. Over the last decade, a paradigm shift from viewing cysteine cathepsins as “simple” protein-degrading enzymes to recognizing them as key signaling molecules has emerged[28], as demonstrated by the crucial roles of cysteine cathepsins (including CatK) in diverse cell-signaling cascades [e.g., peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) /caspase-8-mediated cell apoptosis, TGF-β signaling pathway][29-33].

Figure 1. Complex formation between CatK and C4-S. Electrostatic surface distribution of human CatK. Blue and red areas represent positively and negatively charged surface domains of CatK, respectively (generated using Chimera software). The locations of two

Cathepsin K in osteoporosis, bone cancer and oral diseases

Besides its biological roles in bone turnover, skeletal, heart, lung and intestinal development, and reproduction, CatK expression may be dysregulated in bone resorption disorders such as osteoporosis and bone metastasis[5]. CatK has been identified as the main osteoclastic bone-resorbing protease, and its overexpression is markedly related to extensive bone loss, which is highlighted by the presence of

Oral and maxillofacial abnormalities have been observed in Ctsk(-/-) mice. Similarly, close relationships between defective CatK and oral diseases have been identified in patients with pycnodysostosis[35], as well as in those with periodontitis, peri-implantitis, tooth movement, oral and maxillofacial tumors, root resorption, and periapical disease (see for review:[36]). Extensive histological and ultrastructural changes in cementum, a part of the periodontium, have been observed, which might be linked to compromised proteolytic activity of CatK[37]. Mutations in the human CLCN7, which encodes voltage-gated chloride channel 7 (so-called ClC-7), lead to osteopetrosis associated with deformities in craniofacial morphology and marked tooth dysplasia. Loss of CLCN7 function also results in lysosomal storage in the brain and jaw, and its surrounding tissues, which has been associated with CatK downregulation[38].

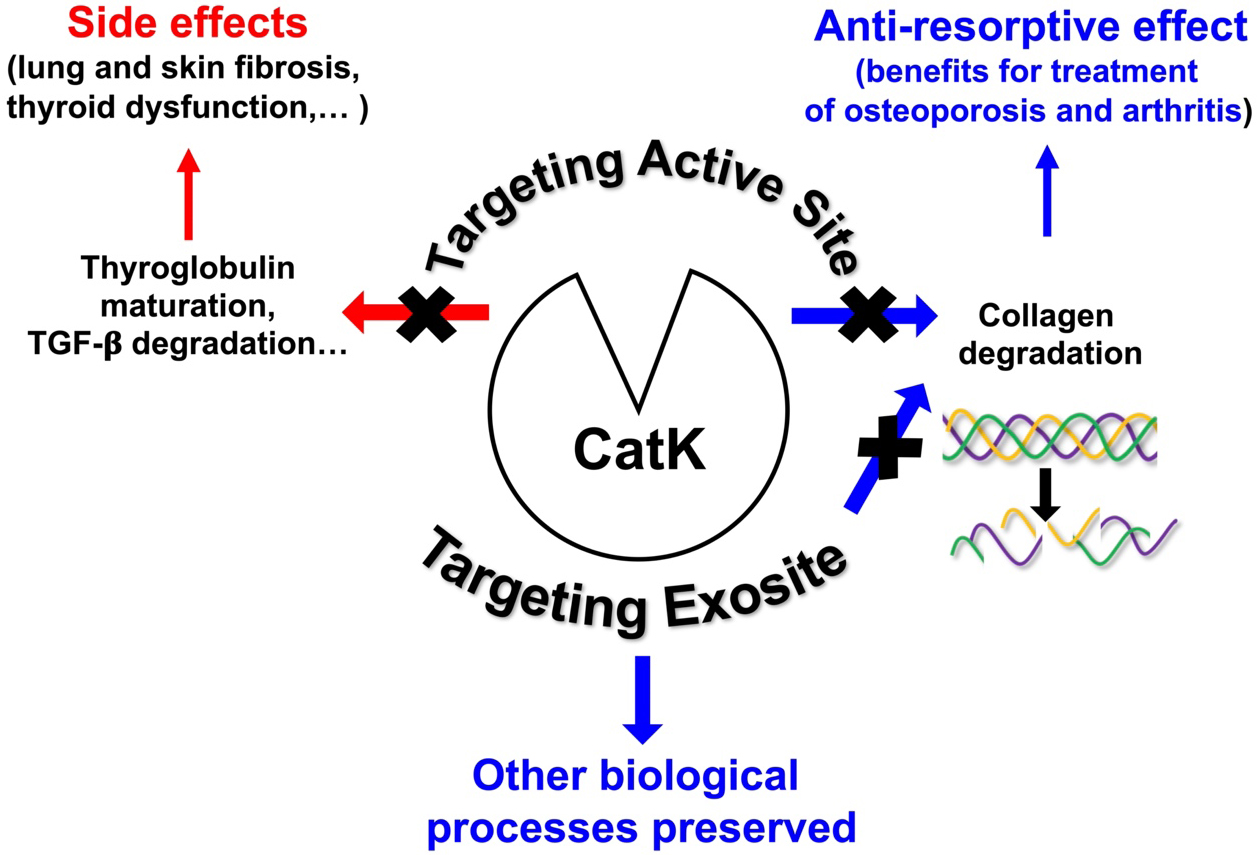

Based on the X-ray crystal structure of CatK, numerous efforts have been made to develop potent, selective, and orally deliverable CatK inhibitors. However, all synthetic inhibitors tested in preclinical or clinical trials so far exclusively target the active site of CatK, thereby blocking both its collagenolytic activity and other peptidase activities such as maturation of thyroid hormones and TGF-β1 hydrolysis. Consequently, blocking the entire active site may lead to unwanted side effects [Figure 2]. Accordingly, Merck & Co. had to discontinue its phase III clinical trials for osteoporosis treatment using Odanacatib, the most promising drug targeting CatK. Compared with other anti-resorptive agents, Odanacatib effectively limited osteoclast-mediated bone resorption without suppressing remodeling (preserving bone formation). However, despite its ability to increase bone mineral density (BMD) and improve bone strength in the spine and hip in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, Odanacatib also increased the risk of cardiovascular side effects, specifically stroke[39]. For a comprehensive update on preclinical and clinical trials conducted with CatK inhibitors, see the recent review:[34]. Thus, new pharmacological approaches are urgently needed to design novel human CatK inhibitors that impair its collagenase activity without affecting other physiological regulatory proteolytic activities. One possible strategy that has emerged in recent years and could help overcome the problems associated with on-target toxicity is to focus on developing either exosite or allosteric inhibitors, such as tanshinones, which are ectosteric inhibitors isolated from the roots and rhizomes of the Chinese medicinal herb Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge (Danshen)[40,41]. It should be noted that inhibition via gene therapy could also limit adverse off-target effects. Indeed, systemic delivery of a

LYMPHANGIOLEIOMYOMATOSIS: CLINICAL FEATURES, DIAGNOSIS AND CURRENT THERAPY

Clinical features

LAM is a rare multisystemic disorder that belongs to the group of cystic pulmonary diseases and mainly affects young women. This disease frequently progresses to chronic respiratory failure. It can occur sporadically or in association with a genetic disorder, tuberous sclerosis (also known as Bourneville’s disease)[43,44]. The prevalence of the sporadic form is estimated to be 3.4-7.8 per million adult women, with an incidence of 0.23 to 0.31 per million women per year[45]. In France, 320 cases of patients with LAM were recorded in April 2021 (RE-LAM-CE: National Register of Lymphangioleiomyomatosis). It is more common in people with tuberous sclerosis, occurring in up to 30% of cases. This pathology affects almost exclusively women of reproductive age, with a median age of 35 years at diagnosis. LAM is considered a slowly progressive neoplastic disease characterized by the proliferation of cells derived from smooth muscle cells within the lymphatic pathways, particularly in the lungs, resulting in progressive cystic lung destruction that leads to deterioration of respiratory function[46]. Clinically, this disease is mainly marked by recurrent pneumothorax, progressively worsening dyspnea on exertion, and eventually chronic obstructive respiratory failure. Respiratory function [i.e., forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO)] correlates with chest computed tomography (CT) and histopathological abnormalities. In addition, renal angiomyolipoma lesions are often observed, which can sometimes cause fatal hemorrhagic events. Since the risk is correlated with tumor size, regular monitoring is therefore required[47].

Diagnosis and LAM markers

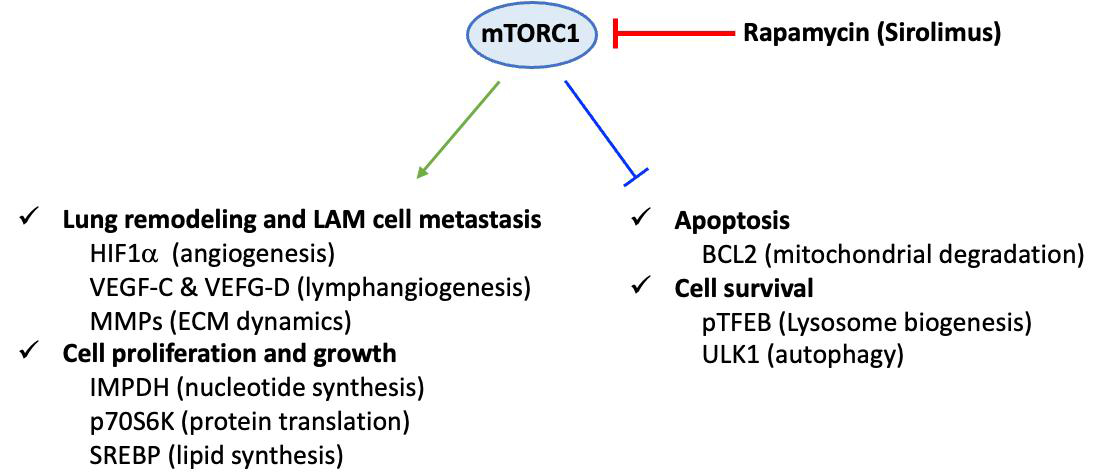

Definitive diagnosis is based on tissue (most often lung) biopsy and/or the association of a clinical picture and a characteristic chest CT appearance. Histopathological diagnosis relies on the presence of cystic cavities and the disseminated proliferation of abnormal or immature smooth muscle cells (LAM cells). LAM cells express smooth muscle α-actin (α-SMA), desmin, vimentin[46] and hormone receptors for estrogen and progesterone[48]. Moreover, LAM cells are characterized by their reactivity with mouse monoclonal antibody HMB45 (i.e., Human Melanoma Black), originally developed against human melanoma[49] and currently used as a diagnostic marker of LAM[50]. The origin of these cells is still unknown, and the main hypothesis suggests a uterine origin with migration via the lymphatic pathways. The mechanisms involved in the pathophysiology of LAM are not fully understood. In particular, they involve lymphangiogenesis, which is notably associated with the overexpression of lymphatic growth factors, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-C and VEGF-D, and their receptor VEGF R3, a marker of lymphatic endothelial cells[51]. The level of blood VEGF-D, which is significantly increased in LAM, is currently the only serum biomarker for its diagnosis. Indeed, high levels of serum VEGF-D (> 800 pg/mL) are specifically observed in LAM, among pulmonary cystic pathologies. The pathophysiology of LAM also includes a genetic component. Mutations associated with tuberous sclerosis involve two tumor suppressor genes: tuberous sclerosis complex 1 (TSC1) and TSC2, which encode hamartin and tuberin, respectively[52]. The TSC1/TSC2 complex inhibits the intracellular signaling pathway involved in cell growth and proliferation, the mTOR-S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) pathway[53]. In sporadic LAM, these mutations are sometimes somatic and de novo, found in lung and kidney lesions, with the most common mutation affecting the TSC2 gene. Mutations in these genes result in the loss of inhibitory function of the hamartin-tuberin complex, leading to constitutive activation of the mTOR pathway, abnormal cell proliferation and growth, and lung remodeling [Figure 3][54]. Conversely, constitutive activation of Raptor-containing mTORC1 leads to downregulation of apoptosis and enhanced cell survival[55].

Figure 3. Dysregulation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) C1 signaling in LAM pathogenesis. Constitutive activation of the Raptor-containing mTOR leads to dysregulated mTOR signaling pathways in LAM cells. Consequently, cell proliferation, cell growth, and lung remodeling, as well as apoptosis and cell survival, are altered. This scheme corresponds to a non-exhaustive summary, emphasizing some key proteins that are specifically linked to mTOR-dependent underexpression or overexpression in LAM cells. Representative upregulated molecules: HIF-1α (hypoxia-inducible factor 1α), VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor)-C and VEGF-D, MMP (matrix metalloproteinase), IMPDH (inosine 5’-monophosphate dehydrogenase), p70S6K (70 kDa ribosomal protein S6 kinase), SREBP (sterol regulatory element-binding protein) and downregulated molecules: BCL2 (B cell lymphoma 2), pTFEB (phosphorylated form of transcription factor EB), ULK1 (unc-51-like autophagy activating kinase 1). LAM: Lymphangioleiomyomatosis; ECM: extracellular matrix.

Current therapy

Recently, purine and pyrimidine nucleotide analogs and immune checkpoint inhibitors have been proposed as potential therapeutic avenues to induce LAM cell death (see for review:[55]). Likewise, preliminary surveys of statins and a cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitor of the coxib family (celecoxib) have been reported, but additional studies with larger LAM cohorts are needed to validate clinical effectiveness. Progesterone, as well as pharmacological inhibitors (oestrogen receptor modulators, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, aromatase inhibitors), has also been attempted as a potential treatment for LAM; however, these interventions produced unreliable and unconvincing results[55]. Conversely, several clinical studies have demonstrated a beneficial effect of mTOR inhibitors, especially rapamycin, on LAM [Figure 3]. Rapamycin (also known as Sirolimus), a macrolide compound naturally produced by the bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus, is currently the reference treatment for this condition[56]. Nevertheless, its effect, which remains only suspensive, is associated with many side effects, notably an increased risk of infection due to immunosuppression induced by treatment with Sirolimus[57]. Sirolimus can also cause hematological disorders, with a very frequent risk of pancytopenia associated with susceptibility to infections[56]. Although rapamycin promotes stabilization of lung function and improves quality of life, cessation of rapamycin treatment results in recurrence of the disease progression, highlighting the urgent need to identify novel targets and contemporary LAM treatments (see for review:[58]).

CATHEPSIN K: A NEW LAM BIOMARKER?

An early immunohistochemical study reported a strong CatK immunoreactivity, which was specifically restricted to LAM specimens, compared with other lung samples from angiomyolipomas and various lung diseases (sarcoidosis, organizing pneumonia, usual interstitial pneumonia, emphysema) used as controls[59]. The specificity of CatK as a putative LAM marker seemed appropriate, since other pulmonary α-SMA-expressing cells are immunonegative for CatK or exhibit only discrete CatK immunoreactivity, such as myofibroblasts in fibroblast foci of usual interstitial pneumonia[59]. Moreover, these α-SMA-expressing cells do not pose diagnostic challenges because of their distinctive morphologies and immunophenotypes. Following this study, Chilosi et al. proposed that CatK could serve as a useful additional biomarker for diagnosis in some ambiguous cases[59]. They also suggested, for the first time, that CatK can contribute to the progressive remodelling of lung parenchyma observed in LAM. In a landmark study, it was hypothesized that LAM nodule-derived proteases cause cyst formation and tissue damage[60]. A gene expression profiling analysis was performed on whole lung tissue. Dongre et al. demonstrated that CatK gene expression was

CATHEPSIN K: AN ADDITIONAL THERAPEUTIC TARGET IN LYMPHANGIOLEIOMYOMATOSIS?

C4-S binding is mandatory to promote the collagenolytic activity of CatK, as stated before (paragraph 1.2). C4-S is predominantly expressed in bone and cartilage, but it is also found throughout the body and contributes to ECM remodeling processes in numerous chronic inflammatory diseases[63]. Although the expression level of C4-S in LAM is currently unknown, the total amount of GAG is increased in lung diseases, including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS), another rare disease[63,64]. In addition to its immunoreactivity, active CatK was detected in LAM-associated fibroblasts. Moreover, active secreted CatK was found in the extracellular medium under in vitro conditions. It is well established that monocyte-derived macrophages acidify their pericellular environment via vacuolar-type

As previously mentioned, inhibition of the mTOR pathway by rapamycin is currently the only reference therapy for LAM. This beneficial effect may be related to the suppression of Warburg metabolism and extracellular acidification. Accordingly, pharmacological inhibitors of carbonic anhydrases and

To summarize, combining the current treatment with rapamycin with inhibition of the collagenolytic activity of CatK by ectosteric inhibitors could be more effective than mTOR inhibition alone. Indeed, a cooperative therapeutic outcome in reducing lung destruction in LAM could be expected compared with single-target therapy. In our opinion, such a dual approach is conceivable despite the lack of experimental evidence at this hypothetical clinical stage.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the patient association “French Lymphangioleiomyomatosis” (FLAM) for their kind support. We thank The University Hospital Center of Tours (CHU Tours, Protocol Collaboration Agreement: RIPH3/LAM-CAK).

Authors’ contributions

Draft the paper: Lalmanach G, Lecaille F, Marchand-Adam S

Prepared the figures: Lecaille F, Lalmanach G

Wrote the paper: Lalmanach G

Revised the paper: Saidi A, Pronost M

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2023.

REFERENCES

1. Lecaille F, Kaleta J, Brömme D. Human and parasitic papain-like cysteine proteases: their role in physiology and pathology and recent developments in inhibitor design. Chem Rev. 2002;102:4459-88.

2. Turk V, Stoka V, Vasiljeva O, et al. Cysteine cathepsins: from structure, function and regulation to new frontiers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1824:68-88.

3. Brix K, Dunkhorst A, Mayer K, Jordans S. Cysteine cathepsins: cellular roadmap to different functions. Biochimie. 2008;90:194-207.

4. Kramer L, Turk D, Turk B. The future of cysteine cathepsins in disease management. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2017;38:873-98.

5. Lecaille F, Brömme D, Lalmanach G. Biochemical properties and regulation of cathepsin K activity. Biochimie. 2008;90:208-26.

6. Brömme D, Lecaille F. Cathepsin K inhibitors for osteoporosis and potential off-target effects. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:585-600.

7. Novinec M, Lenarčič B. Cathepsin K: a unique collagenolytic cysteine peptidase. Biol Chem. 2013;394:1163-79.

8. Qian D, He L, Zhang Q, et al. Cathepsin K: a versatile potential biomarker and therapeutic target for various cancers. Curr Oncol. 2022;29:5963-87.

9. Rocho FR, Bonatto V, Lameiro RF, Lameira J, Leitão A, Montanari CA. A patent review on cathepsin K inhibitors to treat osteoporosis (2011-2021). Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2022;32:561-73.

10. Verbovšek U, Van Noorden CJ, Lah TT. Complexity of cancer protease biology: cathepsin K expression and function in cancer progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;35:71-84.

12. Schechter I, Berger A. On the size of the active site in proteases. I. Papain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1967;27:157-62.

13. Jaffer FA, Kim DE, Quinti L, et al. Optical visualization of cathepsin K activity in atherosclerosis with a novel, protease-activatable fluorescence sensor. Circulation. 2007;115:2292-8.

14. Lecaille F, Weidauer E, Juliano MA, Brömme D, Lalmanach G. Probing cathepsin K activity with a selective substrate spanning its active site. Biochem J. 2003;375:307-12.

15. Lemke C, Benýšek J, Brajtenbach D, et al. An activity-based probe for cathepsin K imaging with excellent potency and selectivity. J Med Chem. 2021;64:13793-806.

16. Richard ET, Morinaga K, Zheng Y, et al. Design and synthesis of cathepsin-k-activated osteoadsorptive fluorogenic sentinel (OFS) probes for detecting early osteoclastic bone resorption in a multiple myeloma mouse model. Bioconjug Chem. 2021;32:916-27.

17. Li Z, Hou WS, Brömme D. Collagenolytic activity of cathepsin K is specifically modulated by cartilage-resident chondroitin sulfates. Biochemistry. 2000;39:529-36.

18. Li Z, Hou W-S, Escalante-Torres CR, et al. Collagenase activity of cathepsin K depends on complex formation with chondroitin sulfate. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:28669-28676.

19. Fonović M, Turk B. Cysteine cathepsins and extracellular matrix degradation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840:2560-70.

20. Brisson L, Reshkin SJ, Goré J, Roger S. pH regulators in invadosomal functioning: proton delivery for matrix tasting. Eur J Cell Biol. 2012;91:847-60.

21. Punturieri A, Filippov S, Allen E, et al. Regulation of elastinolytic cysteine proteinase activity in normal and cathepsin K-deficient human macrophages. J Exp Med. 2000;192:789-99.

22. Brömme D, Okamoto K. Human cathepsin O2, a novel cysteine protease highly expressed in osteoclastomas and ovary molecular cloning, sequencing and tissue distribution. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1995;376:379-384.

23. Quintanilla-Dieck MJ, Codriansky K, Keady M, Bhawan J, Rünger TM. Expression and regulation of cathepsin K in skin fibroblasts. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:596-602.

24. Friedrichs B, Tepel C, Reinheckel T, et al. Thyroid functions of mouse cathepsins B, K, and L. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1733-45.

25. Tepel C, Brömme D, Herzog V, Brix K. Cathepsin K in thyroid epithelial cells: sequence, localization and possible function in extracellular proteolysis of thyroglobulin. J Cell Sci. 2000;113 Pt 24:4487-98.

26. Bühling F, Waldburg N, Reisenauer A, et al. Lysosomal cysteine proteases in the lung: role in protein processing and immunoregulation. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:620-628.

27. Zhang D, Leung N, Weber E, Saftig P, Brömme D. The effect of cathepsin K deficiency on airway development and TGF-β1 degradation. Respir Res. 2011;12:72.

29. Chen H, Wang J, Xiang MX, et al. Cathepsin S-mediated fibroblast trans-differentiation contributes to left ventricular remodelling after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;100:84-94.

30. Yue X, Piao L, Wang H, et al. Cathepsin K deficiency prevented kidney damage and dysfunction in response to 5/6 nephrectomy injury in mice with or without chronic stress. Hypertension. 2022;79:1713-23.

31. Zhang X, Zhou Y, Yu X, et al. Differential roles of cysteinyl cathepsins in tgf-β signaling and tissue fibrosis. iScience. 2019;19:607-22.

32. Lalmanach G, Saidi A, Marchand-Adam S, Lecaille F, Kasabova M. Cysteine cathepsins and cystatins: from ancillary tasks to prominent status in lung diseases. Biol Chem. 2015;396:111-30.

33. Kasabova M, Joulin-Giet A, Lecaille F, et al. Regulation of TGF-β1-driven differentiation of human lung fibroblasts: emerging roles of cathepsin B and cystatin C. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:16239-51.

34. Biasizzo M, Javoršek U, Vidak E, Zarić M, Turk B. Cysteine cathepsins: a long and winding road towards clinics. Mol Aspects Med. 2022;88:101150.

35. Henriksen K, Thudium CS, Christiansen C, Karsdal MA. Novel targets for the prevention of osteoporosis - lessons learned from studies of metabolic bone disorders. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2015;19:1575-84.

36. Wen X, Yi LZ, Liu F, Wei JH, Xue Y. The role of cathepsin K in oral and maxillofacial disorders. Oral Dis. 2016;22:109-15.

37. Xue Y, Wang L, Xia D, et al. Dental abnormalities caused by novel compound heterozygous CTSK Mutations. J Dent Res. 2015;94:674-81.

38. Zhang Y, Ji D, Li L, Yang S, Zhang H, Duan X. ClC-7 Regulates the pattern and early development of craniofacial bone and tooth. Theranostics. 2019;9:1387-400.

39. McClung MR, O'Donoghue ML, Papapoulos SE, et al. LOFT Investigators. Odanacatib for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: results of the LOFT multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial and LOFT Extension study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:899-911.

40. Panwar P, Law S, Jamroz A, et al. Tanshinones that selectively block the collagenase activity of cathepsin K provide a novel class of ectosteric antiresorptive agents for bone. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175:902-23.

41. Panwar P, Xue L, Søe K, et al. An ectosteric inhibitor of cathepsin K inhibits bone resorption in ovariectomized mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32:2415-30.

42. Yang YS, Xie J, Chaugule S, et al. Bone-Targeting AAV-mediated gene silencing in osteoclasts for osteoporosis therapy. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2020;17:922-35.

43. Cottin V, Archer F, Khouatra C, Lazor R, Cordier JF. Lymphangioléiomyomatose pulmonaireLymphangioleiomyomatosis. Presse Med. 2010;39:116-25.

44. Johnson SR, Cordier JF, Lazor R, et al. Review Panel of the ERS LAM Task Force. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis and management of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:14-26.

45. Harknett EC, Chang WY, Byrnes S, et al. Use of variability in national and regional data to estimate the prevalence of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. QJM. 2011;104:971-9.

46. Henske EP, McCormack FX. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis - a wolf in sheep’s clothing. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3807-16.

47. Taveira-DaSilva AM, Moss J. Epidemiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs. 2016;4:369-78.

48. Ruiz de Garibay G, Herranz C, Llorente A, et al. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis biomarkers linked to lung metastatic potential and cell stemness. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132546.

49. Gown AM, Vogel AM, Hoak D, et al. Monoclonal antibodies specific for melanocytic tumors distinguish subpopulations of melanocytes. Am J Pathol. 1986;123:195-203.

50. Matsumoto Y, Horiba K, Usuki J, Chu SC, Ferrans VJ, Moss J. Markers of cell proliferation and expression of melanosomal antigen in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;21:327-36.

51. Young L, Lee HS, Inoue Y, et al. MILES Trial Group. Serum VEGF-D a concentration as a biomarker of lymphangioleiomyomatosis severity and treatment response: a prospective analysis of the Multicenter International Lymphangioleiomyomatosis Efficacy of Sirolimus (MILES) trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:445-52.

52. Gupta N, Henske EP. Pulmonary manifestations in tuberous sclerosis complex. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2018;178:326-37.

53. Smolarek TA, Wessner LL, McCormack FX, Mylet JC, Menon AG, Henske EP. Evidence that lymphangiomyomatosis is caused by TSC2 mutations: chromosome 16p13 loss of heterozygosity in angiomyolipomas and lymph nodes from women with lymphangiomyomatosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:810-5.

54. Yu J, Henske EP. mTOR activation, lymphangiogenesis, and estrogen-mediated cell survival: the “perfect storm” of pro-metastatic factors in LAM pathogenesis. Lymphat Res Biol. 2010;8:43-9.

55. McCarthy C, Gupta N, Johnson SR, Yu JJ, McCormack FX. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: pathogenesis, clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:1313-27.

56. Harari S, Spagnolo P, Cocconcelli E, Luisi F, Cottin V. Recent advances in the pathobiology and clinical management of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2018;24:469-76.

57. Courtwright AM, Goldberg HJ, Henske EP, El-Chemaly S. The effect of mTOR inhibitors on respiratory infections in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26:160004.

58. Moir LM. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: Current understanding and potential treatments. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;158:114-24.

59. Chilosi M, Pea M, Martignoni G, et al. Cathepsin-k expression in pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:161-166.

60. Dongre A, Clements D, Fisher AJ, Johnson SR. Cathepsin K in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: LAM cell-fibroblast interactions enhance protease activity by extracellular acidification. Am J Pathol. 2017;187:1750-62.

61. Caliò A, Brunelli M, Gobbo S, et al. Cathepsin K: a novel diagnostic and predictive biomarker for renal tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:2441.

62. Rolim I, Makupson M, Lovrenski A, Farver C. Cathepsin K is superior to HMB45 for the diagnosis of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2022;30:108-12.

63. Westergren-Thorsson G, Hedström U, Nybom A, et al. Increased deposition of glycosaminoglycans and altered structure of heparan sulfate in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2017;83:27-38.

64. Chazeirat T, Denamur S, Bojarski KK, et al. The abnormal accumulation of heparan sulfate in patients with mucopolysaccharidosis prevents the elastolytic activity of cathepsin V. Carbohydr Polym. 2021;253:117261.

65. Kant S, Kumar A, Singh SM. Bicarbonate transport inhibitor SITS modulates pH homeostasis triggering apoptosis of Dalton’s lymphoma: implication of novel molecular mechanisms. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;397:167-78.

66. Pacchiano F, Carta F, McDonald PC, et al. Ureido-substituted benzenesulfonamides potently inhibit carbonic anhydrase IX and show antimetastatic activity in a model of breast cancer metastasis. J Med Chem. 2011;54:1896-902.

67. Miller S, Stewart ID, Clements D, Soomro I, Babaei-Jadidi R, Johnson SR. Evolution of lung pathology in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: associations with disease course and treatment response. J Pathol Clin Res. 2020;6:215-26.

68. Taveira-Dasilva AM, Stylianou MP, Hedin CJ, Hathaway O, Moss J. Bone mineral density in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:61-7.

69. Iakymenko OA, Delma KS, Jorda M, Kryvenko ON. Cathepsin K (Clone EPR19992) demonstrates uniformly positive immunoreactivity in renal oncocytoma, chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, and distal tubules. Int J Surg Pathol. 2021;29:600-5.

70. Seo SU, Woo SM, Kim MW, et al. Cathepsin K inhibition-induced mitochondrial ROS enhances sensitivity of cancer cells to anti-cancer drugs through USP27x-mediated Bim protein stabilization. Redox Biol. 2020;30:101422.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].