Short-term L-arabinose administration alleviates MASLD by remodeling gut microbiota and activating hepatic ATF5-dependent mitochondrial unfolded protein response

Abstract

Aim: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) involves gut microbial dysbiosis and mitochondrial stress, yet the molecular link between these processes remains unclear. This study explored whether short-term L-arabinose (LA) supplementation mitigates MASLD by modulating the gut-liver axis and mitochondrial adaptive signaling.

Methods: A murine early-stage fatty liver model was established and treated orally with LA for four weeks. Gut microbial changes were assessed by 16S ribosomal RNA gene (16S rRNA) sequencing and functional prediction, while hepatic mechanisms were examined through activating transcription factor 5 (ATF5) gain- and loss-of-function experiments both in vivo and in vitro.

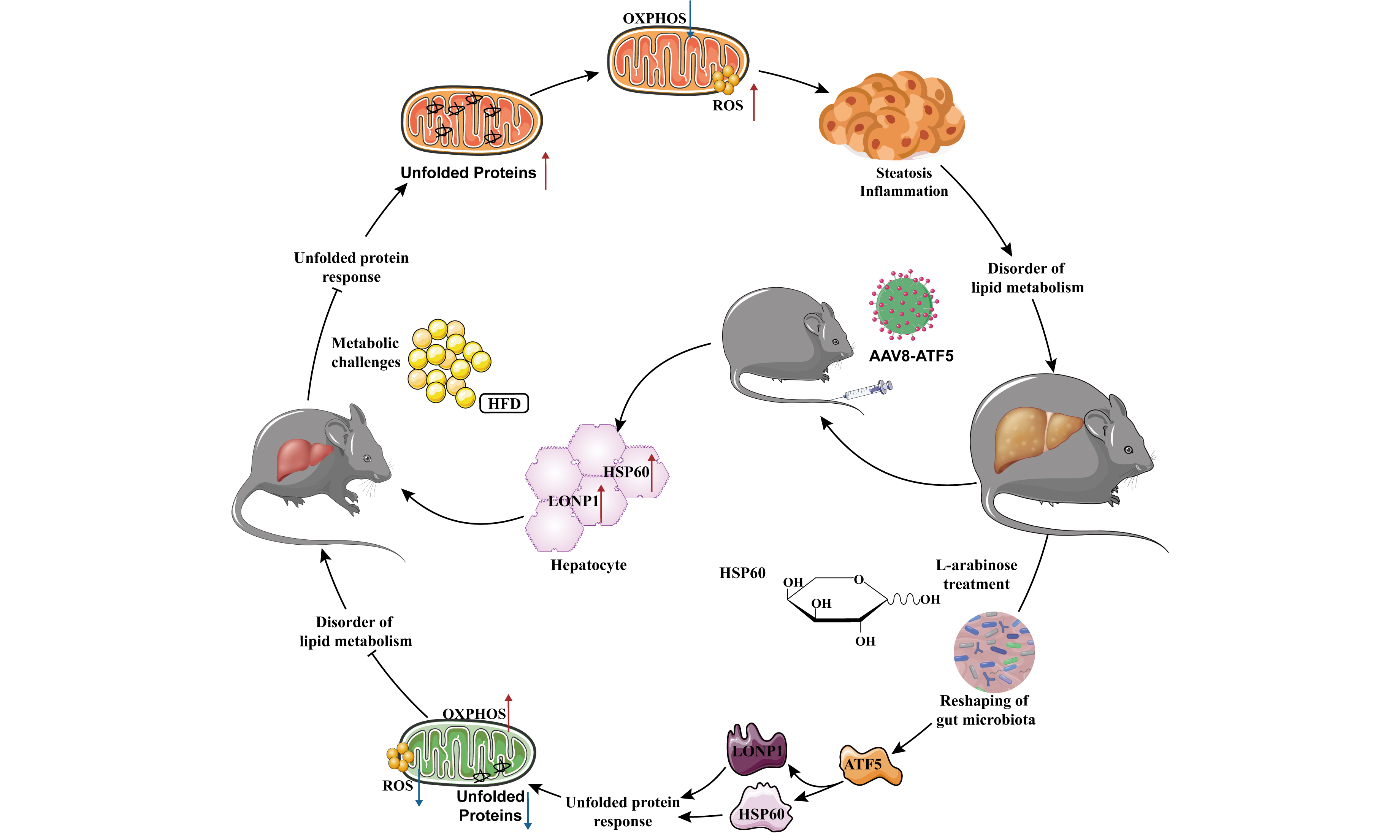

Results: Short-term LA administration significantly reshaped gut microbiota, enriching short-chain fatty acid-producing taxa and improving hepatic lipid metabolism. Mechanistically, LA enhanced hepatic expression of ATF5, leading to the upregulation of mitochondrial chaperone heat shock protein 60 (HSP60) and protease Lon protease 1 (LONP1), thereby initiating the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt). Activation of UPRmt restored mitochondrial integrity, reduced oxidative stress, and attenuated hepatic lipid deposition. Silencing ATF5 abolished these protective effects, confirming its central regulatory role.

Conclusion: Short-term LA treatment alleviates MASLD by reprogramming gut microbiota and activating hepatic ATF5-mediated UPRmt signaling. These findings reveal a novel gut–mitochondrial regulatory pathway that links microbial metabolism to hepatic mitochondrial proteostasis, providing new mechanistic insight and therapeutic potential for metabolic liver disease.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), redefined from non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), highlights the pivotal contribution of metabolic dysregulation to hepatic injury[1]. MASLD encompasses a continuum from simple steatosis to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma[2]. MASLD development is closely tied to a combination of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors, which together contribute to hepatic ectopic lipid deposition. This is driven by dyslipidemia, inflammatory infiltration, oxidative stress, and other underlying factors[3]. Notably, the concept of the “intestinal-hepatic axis” has gained traction as a key mediator in MASLD pathogenesis[4]. Individuals with MASLD exhibit distinct gut microbial profiles compared with healthy controls, including enrichment of proinflammatory taxa such as Proteobacteria and Fusobacteria[5]. Increasing evidence suggests that gut microbiota play a pivotal role in MASLD progression through mechanisms such as promoting obesity, producing endogenous ethanol, triggering inflammatory responses, and modulating choline metabolism[6,7]. These findings have led to growing interest in targeting the gut microbiota as a potential strategy for MASLD intervention.

L-arabinose (LA), a low-calorie functional monosaccharide, has shown promise in modulating energy metabolism by inhibiting sucrose absorption[8], reducing fat accumulation[9], promoting beneficial probiotics, and improving intestinal microecology[10,11]. This compound has attracted significant attention and is included in the American Medical Association’s list of anti-obesity nutritional supplements. Studies have demonstrated that LA can alleviate lipid metabolism disorders and inflammatory responses in obese mice by improving insulin sensitivity and gut microbiota composition[12]. Furthermore, LA has been shown to significantly alter gut microbial composition and increase the levels of bifidobacteria and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), both in vivo and in vitro[13]. These modifications to the intestinal flora and mitochondrial function are crucial for the development of metabolic disorders[14]. However, the full impact of short-term LA application on these processes remains underexplored. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a well-established contributor to MASLD development with several mechanisms, including oxidative stress, insulin resistance, inflammatory invasion, and lipid metabolic remodeling, implicated in the disease[15-17]. Mitochondrial heat shock protein 60 (HSP60) is a key stress response factor and molecular chaperone in mitochondria, regulating energy metabolism in adipose tissue and contributing to obesity[18]. Furthermore, HSP60 serves as a critical downstream factor in the activating transcription factor 5 (ATF5)-induced mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt), which plays a role in tubulointerstitial injury in diabetic nephropathy[19]. While HSP60’s involvement in MASLD has been noted, the specific role of the ATF5/HSP60 axis in this disease, as well as the potential action of LA in regulating hepatic lipid metabolism, has not been fully investigated.

This study investigated whether short-term LA intervention alleviates MASLD by integrating gut microbiota remodeling with hepatic mitochondrial adaptive responses. Structural changes in the gut microbiota were assessed using 16S ribosomal RNA gene (16S rRNA) amplicon sequencing, and the functional impact of LA on cellular processes, particularly mitochondrial stress, was evaluated using Tax4Fun functional prediction. Building on these results, we identified ATF5 as a key molecular player by performing enrichment analysis of specific pathways and confirmed its role in MASLD through in vivo and in vitro experiments. Using liver-targeted viral vectors, RNA interference (RNAi), and gene overexpression techniques, we demonstrated that LA alleviates high-fat-diet-induced MASLD by reducing mitochondrial stress through inducing ATF5 expression. Our findings provide new insights into potential strategies for clinical intervention in MASLD, shedding light on the role of LA in regulating mitochondrial function and gut microbiota as therapeutic avenues.

METHODS

Materials and reagents

LA (molecular weight of 150.13 g/mol) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Palmitic acid (PA) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The purified mouse ATF5 gene overexpression adeno-associated virus serotype 8 (AAV8) serotype adeno-associated virus and AAV8-thyroxine-binding globulin promoter (TBG)-(green fluorescent protein) GFP were obtained from ViGene Biosciences (Shandong, China). Fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA) was sourced from Yeasen Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits [triglyceride (TG) and total cholesterol (TC)] were purchased from Applygen (Beijing, China). A Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay Kit with Tetramethylrosamine (TMRE) and Reactive Oxygen Species Assay Kit were purchased from Beyotime (Shanghai, China). AML12 cells (alpha mouse liver 12) were purchased from BeNa Culture Collection (Henan, China). AML12 Cell Complete Medium was purchased from Wuhan Pricella Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). The Lipid Droplet-Red Fluorescent Detection Kit (Nile Red) was purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). An Oil Red O Stain Kit (For Cultured Cells) was purchased from Solarbio (Beijing, China). Antibodies such as ATF5 (ab184923) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK), while other antibodies, such as HSP60 (15282-1-AP), Lon protease 1 (LONP1, 15440-1-AP), and beta Actin (66009-1-Ig), were purchased from Proteintech (Wuhan, China).

Animal experiments

All procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shandong Institute of Endocrine & Metabolic Diseases.

The male C57BL/6j mice (6 ~ 8-week-old) used in this study were purchased from the Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology company. All mice were housed with a 12h light/dark cycle in a temperature-controlled environment, with free access to water and food. The different animal models designed for the experiment are described in detail below.

Short-term L-arabinose gavage model for early-stage fatty liver

After one week of acclimatization, C57BL/6j mice were randomly assigned to groups with no significant difference in body weight. Mice were randomly allocated into four groups (5-6 mice per group): a blank control group (NCD), a model control group (HFD), a control group (NCD + LA), and a LA treatment group (HFD + LA). All groups concurrently underwent a 4-week regimen of dietary intervention and gavage administration: mice in the normal chow diet (NCD) and high-fat diet (HFD) groups received 0.9% saline via oral gavage, while those in the NCD + LA and HFD + LA groups received 500 mg/kg LA (suspended at 10 mg/ml in 0.9% normal saline) via gavage for four weeks. All gavage treatments were performed six times per week. The successful induction of the early-stage fatty liver model was confirmed by a significant increase in hepatic TG content in HFD-fed mice compared to the NCD controls after the 4-week intervention.

Mouse model of virus overexpression injected into the tail vein

Mice were randomly assigned to the following groups (5-6 mice per group): a blank control group (NCD), a model control group (HFD), a control group (NCD + ATF5), and an Activating Transcription Factor 5 Overexpression group (HFD + ATF5). The MASLD model was established by 8-week feeding with NCD or HFD. Following 8 weeks of high-fat or normal chow diet feeding, an ATF5-overexpressing animal model was established via tail vein injection. The control virus [AAV8-short-hairpin Control (-shCtr)] and ATF5-overexpressing virus (AAV8-ATF5) stock solutions had titers of 2.89 × 1013 vg/mL and 3.21 × 1013 vg/mL, respectively, and were administered at a dose of 5 × 1011 vg per mouse through tail vein injection. Following viral delivery, the original dietary regimens were maintained for subsequent experiments. The Transcription Factor 5 Overexpression Virus is a specially designed viral vector that effectively promotes Transcription Factor 5 expression and activity, whereas the control virus contains no therapeutic components and is only used to mimic the injection process of the experimental group. MASLD model validation was based on hepatic lipid deposition [hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining], > 20% body weight gain, and significantly increased random blood glucose levels in the model group versus controls.

Cell culture

Lipid deposition cell model

AML12 cells were seeded at approximately 25%-30% confluency and cultured in AML12 Cell Complete Medium for 24 h until reaching 50%-60% confluency. PA (0.4 mM) was then added to induce a lipid-deposition state in the cells. An equal amount of BSA was added to control cells as a negative control. After a 24-h treatment period, the cells were harvested for subsequent experiments. The success of the lipid deposition model was assessed quantitatively by oil red staining.

Activating transcription factor 5 overexpression or knockdown cell model

We used AML12 cells and cultured them in AML12 Cell Complete Medium. Once the cells achieved 60%-80% confluence, AML12 cells were subjected to transfection with siRNAs or plasmids utilizing Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher, USA) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Post 24 h of transfection, the cells were exposed to 0.4 mmol/L PA (0.4 mM) for 24 h prior to harvesting. The ATF5siRNA [sequence: GGGAGAUCCAGUACGUGAA (dt)(dt)] and the pLV4ltr- hATF5 plasmid were sourced from Tsingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (China). Scrambled small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and the empty pLV4ltr vector served as negative controls in parallel cultures.

Daily husbandry of animals, dynamic indicator monitoring and sample collection

During the feeding period, animals were observed daily for fur color, mental state, and motor abilities. In accordance with the feeding schedule, body weight changes were regularly recorded every week, and fasting blood glucose levels were determined at scheduled intervals to monitor changes post-model establishment and drug administration. The primary procedure involved fasting the animals for 6 h, with access to water from 8 AM on the last day of each cycle, followed by blood collection from the tip of the tail to determine fasting blood glucose levels using an ACCU-CHEK glucometer. Mice were fasted overnight with free access to water before sacrifice. Anesthesia was induced via isoflurane inhalation, followed by blood collection through orbital puncture and cervical dislocation. Subcutaneous adipose tissue, liver, and colonic contents were then collected. Blood samples were allowed to clot for 30 min and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min to separate serum. The serum was transferred into 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tubes and stored at -80 °C. Subcutaneous adipose tissue and liver were weighed, with portions either fixed in formalin for histopathological examination or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C. Colonic contents were collected in sterile tubes, immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80 °C for subsequent microbiological analysis.

Glucose tolerance test and insulin tolerance test

For glucose tolerance test (GTT), following a 16 h fast, the baseline (0 min) blood glucose level at the tail tip was measured using a Roche Accu-Check Advantage glucometer (Roche Diagnostic, Basel, Switzerland); then, 2 g/kg glucose was administered via intraperitoneal injection. For insulin tolerance test (ITT), mice that fasted for 4 h received an intraperitoneal injection of insulin at 0.75IU/kg. Blood glucose levels were assessed at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min post glucose or insulin injection, and the area under curve (AUC) of the time-blood glucose concentration curve was computed.

Quantification of TG levels

The TG levels in hepatocytes (6 × 106 cells) and liver tissue (~ 20 mg) were quantified using the E1013 kit from Applygen Technologies Inc. (Beijing, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Hepatocytes and tissue were homogenized in the provided TG assay kit lysate. A portion of the supernatant was used to measure total protein concentration with the bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) Protein Assay Kit (P0009; Beyotime, China). The remaining supernatant was heated in a 70 °C water bath for 10 min. After cooling to 25 °C, samples were vortexed and centrifuged at 2,000 ×g for 5 min at 25 °C. Then, 10 µL of supernatant was mixed with 190 µL of color-developing reagent and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. The absorbance at 550 nm correlated with the TG concentration in each sample.

Measurement of TC content

TC content in hepatocytes (6 × 106 cells) and liver tissue (~ 100 mg) was determined using a commercially available assay kit (E1015; Beijing Prilay Gene Technology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Hepatocyte or liver tissue samples were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and homogenized with lysis buffer at the specified concentration ratio. Measure the total protein concentration in a portion of the supernatant using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (P0009; Biyun Tian Company). Heat the remaining supernatant in a 70 °C water bath for 10 min, cool to room temperature, then centrifuge at 2,000 ×g for 5 min. Collect the supernatant for enzymatic assays. Prepare the working solution by mixing reagents R1 and R2 at a 4:1 ratio. Add 190 µL of working solution to a microplate. Add 10 µL of blank control, standard, or test sample to each well. Incubate at 37 °C or 25 °C for 20 min before measuring absorbance. Absorbance at 550 nm correlates positively with TC concentration in the sample. Calculate sample concentrations using the standard curve, and correct TC content per milligram of protein concentration or cell count.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

In line with the guidelines from ComWin Biotech Co., Ltd (Beijing, China), the RNA prep pure kit was utilized to isolate total RNA from frozen liver tissues and cells. Subsequently, complementary DNA (cDNA) was generated from total RNA using the All-in-one 1st Stand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (Novoprotein Scientific Inc., Shanghai, China). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was executed with the SYBR mixture (ComWin Biotech Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) and analyzed on the LightCycler480 system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). All primers [Table 1] were manufactured by Tsingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (China). Relative messenger RNA (mRNA) expression levels were determined using the 2^-ΔΔCt method.

Nucleotide sequences of primers

| Target genes | Primer sequences (5’ to 3’) | |

| GAPDH | F: CCATCACTGCCACCCAGAAGACT | R: ATGACCTTGCCCACAGCCTT |

| β-Actin | F: CCTTCGTTGCCGGTCCACACC | R: CTCTTGCTCTGGGCCTCGTCACC |

| ATF5 | F: CGCCCGCCCAGCCCCTTATCCT | R: GCCTCGCCCTCTGCCCGCTTC |

| HSP60 | F: GTTCAGTCCATTGTCCCTGCTCT | R: ACCAATGGCTTCCGATGAGCA |

| LONP1 | F: ACCTGCCGCTCATCGCCATCACC | R: CCAGGCTCTCCACCACGTCCG |

Western blotting assay

To obtain whole protein extracts, rat livers were treated with lysis buffer containing protease and phosphorylation inhibitors. Total proteins were separated via Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate - PolyAcrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. After the membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk, they were incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight and secondary antibodies the next day. The protein bands were visualized using Odyssey CLx (LI-COR Biosciences, USA). The levels of target proteins were standardized relative to the loading controls, such as β-actin, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), or Tubulin.

Nile red staining

Cells were stabilized using 4% paraformaldehyde, rinsed three times with PBS, stained with Nile red (Solarbio, Beijing, China) at 37 °C for 30 min, and washed again three times. Subsequently, cellular analysis was performed via the Delta Vision Ultra imaging system [GE Healthcare Life Sciences (GE)].

TMRE

The mitochondrial membrane potential was assessed using the TMRE assay kit (Beyotime, C2001S). Under normal conditions, the interior of mitochondria exhibits a significant negative charge, which allows the cationic probe TMRE to accumulate in the mitochondrial matrix upon cell entry, producing a bright orange-red fluorescence. When the mitochondrial membrane potential dissipates, the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) remains open, causing TMRE to be released into the cytoplasm and leading to a significant reduction in the orange-red fluorescence within mitochondria.

To perform the assay, 1 mL of TMRE staining working solution was added to the cells. The cells were then incubated at 37 °C in a cell culture incubator for 15 min. Following the incubation period, the supernatant was aspirated, and the cells were washed twice with cell culture medium to remove any unbound TMRE. Finally, the fluorescence intensity of the solution was detected using SpectraMax iD3 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, CA, USA).

Oil red staining

AML12 cells were stained with the Oil Red O Stain Kit (for cultured cells).

For the preparation of oil red (dissolved in propylene glycol), 1g of powder (Solarbio, O8010) is dissolved in 100ml of propylene glycol, thoroughly stirred and dissolved, then filtered through filter paper and allowed to stand overnight. The filtered solution is the ready-to-use oil red O staining working solution, of which each frozen section requires 0.2mL.

Staining was carried out as follows: 10 min with propylene glycol, 10-15 min with oil red at 65 °C, 5 s with 70% propylene glycol, 1-2 min with 50% propylene glycol, and continuous soaking with 20% propylene glycol. We stained the nucleus with hematoxylin for 2 s, differentiated it with 1% Ethanol hydrochloride, and rinsed with running water to return to blue.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 10.0). Data are presented as mean ± Standard Deviations (SDs). For data meeting assumptions of homogeneity of variances and normal distribution, comparisons between two groups were analyzed using two-tailed Student’s t-test, while comparisons among three or more groups were assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When ANOVA revealed significant differences, Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) post hoc test was conducted for pairwise comparisons. Statistical significance was defined as follows: not significant (ns), */# P < 0.05, **/## P < 0.01, ***/### P < 0.001.

RESULTS

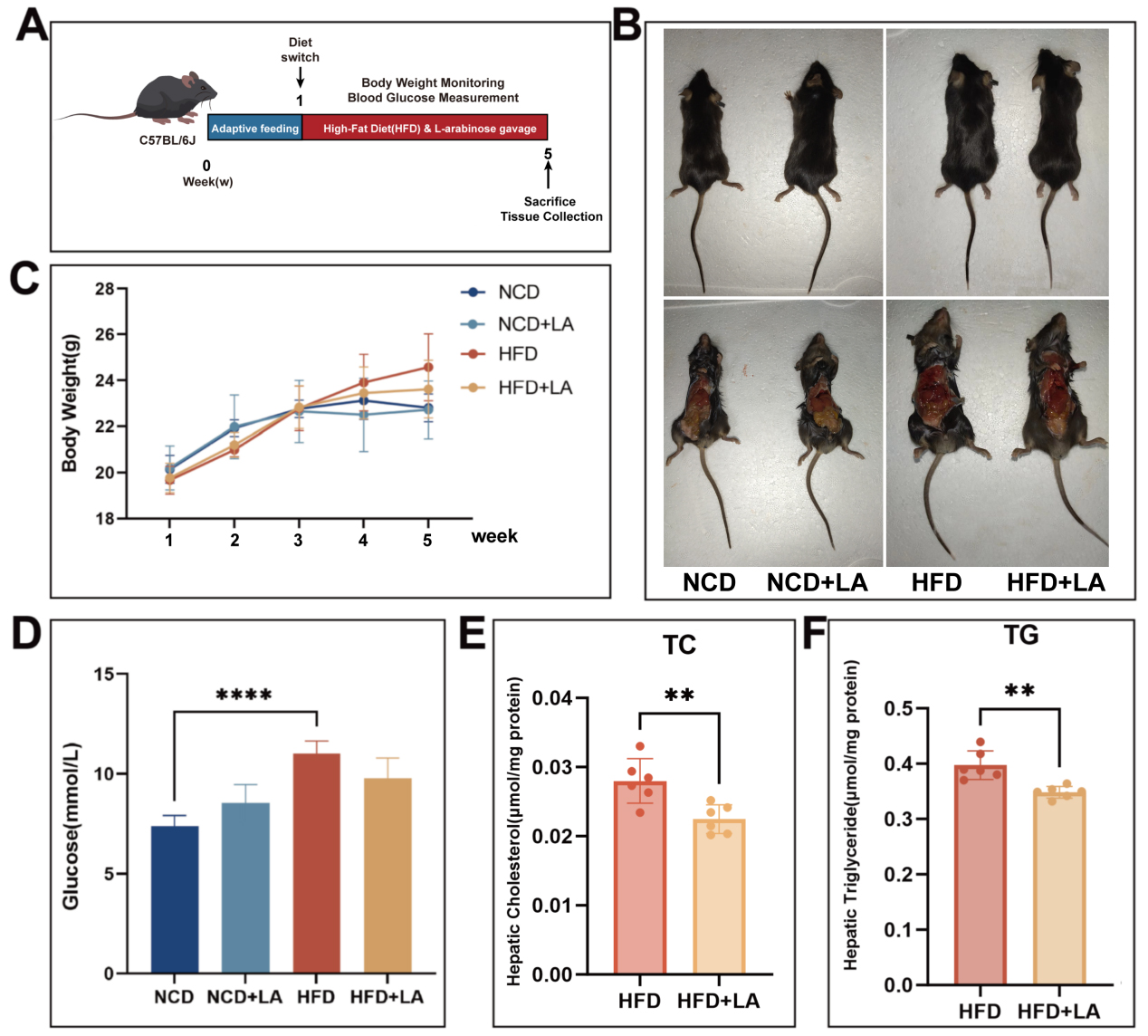

L-arabinose alleviates high-fat-diet-induced hepatic lipid deposition

To assess how short-term LA modulates hepatic lipid homeostasis, mice were maintained on a HFD and orally administered LA. The experimental design is depicted in Figure 1A. Macroscopic examination revealed that the livers of HFD + LA mice exhibited a healthier appearance, with lighter color and firmer texture compared to HFD controls [Figure 1B]. No significant differences in body weight or random blood glucose levels were observed between HFD and HFD + LA groups [Figure 1C and D]. To better reflect the modulatory effect of LA on hepatic lipid metabolism disorders, we measured the hepatic TG and cholesterol content in mice and found that it was significantly increased in the HFD group, whereas LA gavage mitigated this alteration [Figure 1E and F]. In conclusion, short-term LA gavage can improve lipid metabolism disorders and alleviate hepatic lipid deposition.

Figure 1. Short-term oral administration of L-arabinose can reduce body weight in mice. (A) construction process of L-arabinose gavage mouse model; (B) photos taken during mice sacrifice; (C) body weight during oral administration of arabinose in mice; (D) mouse blood glucose at week 12; (E) cholesterol content in mouse liver (μmol/mg protein); (F) Triglyceride content in mouse liver (μmol/mg protein). “*”Significant difference between the model group and gavage group. (****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, and *P < 0.05). NCD: Normal chow diet; HFD: high-fat diet; LA: L-arabinose; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglyceride.

L-arabinose upregulates the abundance of beneficial gut bacteria in mice

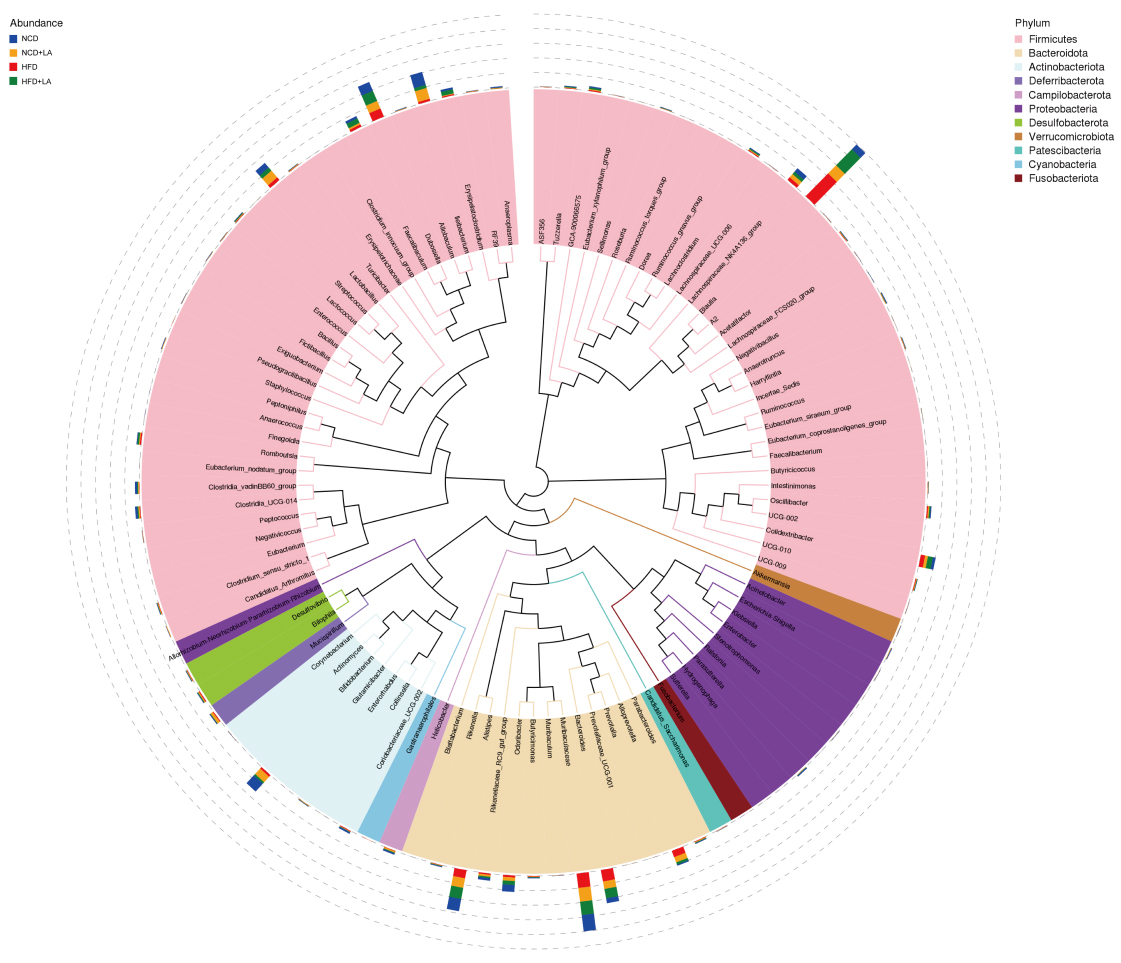

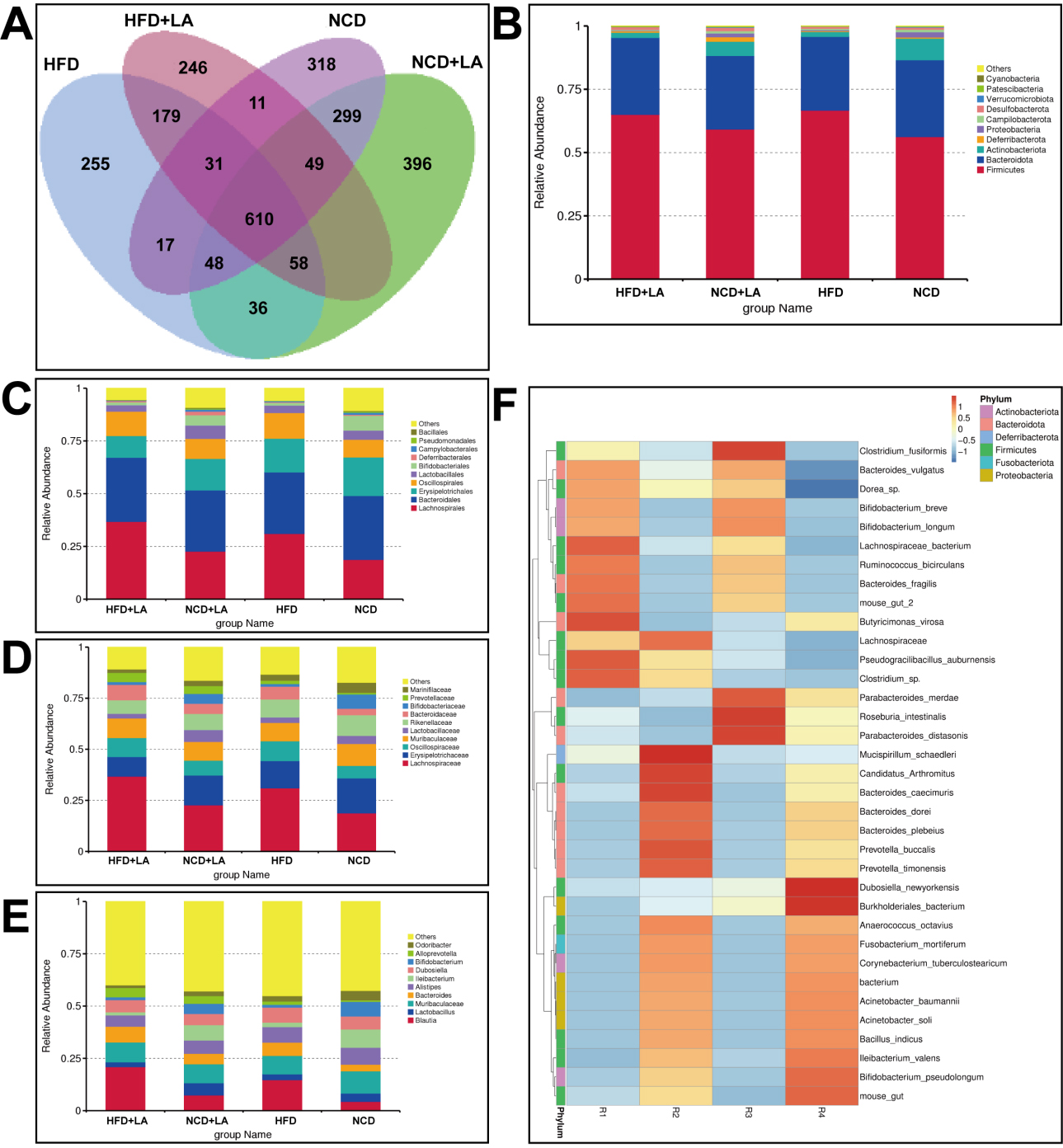

LA has a different structure from common monosaccharides; it lacks corresponding transport proteins and is absorbed inefficiently in the small intestine. Currently, it is widely believed that LA acts in two ways: by inhibiting sucrase activity and entering the colon to regulate intestinal flora[20]. However, the specific molecular mechanism of action through which LA regulates metabolism-associated fatty liver disease has not been fully investigated. Thus, we analyzed the intestinal contents of mice treated with LA gavage using 16S rRNA technology. The representative sequences of the top 100 genera were aligned and visualized on a phylogenetic tree [Figure 2]. Based on the resulting feature set, a Venn diagram demonstrated both shared and unique microbial profiles across NCD, HFD, and LA-treated groups [Figure 3A]. Among all samples, 610 shared operational taxonomic units were identified, whereas 246, 396, 255, and 318 features were unique to the NCD + LA, HFD + LA, HFD, and NCD groups, respectively. The top ten phyla - including Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, Actinobacteriota, and Proteobacteria - were conserved across all groups. At the phylum level, LA supplementation increased Deferribacterota, Cyanobacteria, and Desulfobacterota while reducing Proteobacteria, Campilobacterota, and Verrucomicrobia, partially restoring the disrupted Firmicutes/Bacteroidota ratio [Figure 3B]. At the family level, LA increased Lachnospiraceae and Bacteroidaceae but lowered Erysipelotrichaceae, Rikenellaceae, and Marinifilaceae [Figure 3C]. Genus-level changes showed enrichment of Blautia, Bacteroides, and Alloprevotella, along with a decline in Alistipes, Dubosiella, and Odoribacter [Figure 3D]. At the species level, LA promoted Lachnospiraceae_bacterium and Bacteroides_vulgatus while reducing Ileibacterium_valens and Dubosiella_newyorkensis [Figure 3E]. Heatmap analysis of the top 35 taxa [Figure 3F] confirmed that LA markedly enhanced beneficial bacteria, notably Dorea sp., Lachnospiraceae bacterium, and Ruminococcus bicirculans. These findings suggest that LA supplementation reshapes the gut microbial community, increasing the abundance of health-promoting species.

Figure 2. Phylogenetic trees at the genus level for various groups at the same time point. (n = 5-6 for each group). NCD: Normal chow diet; HFD: high-fat diet; LA: L-arabinose.

Figure 3. Characteristics of gut microbiota in mice. (A) Venn diagram of characteristic sequences of mice in each group; (B) the top ten microbial populations in each group at the phyla level; (C) at the family level; (D) at the genus level; (E) at the species level; (F) a heatmap of the top 35 strains with total abundance at the taxonomic level. (n = 5-6 for each group). NCD: Normal chow diet; HFD: high-fat diet; LA: L-arabinose.

L-arabinose enhances the diversity and abundance of intestinal microorganisms in mice

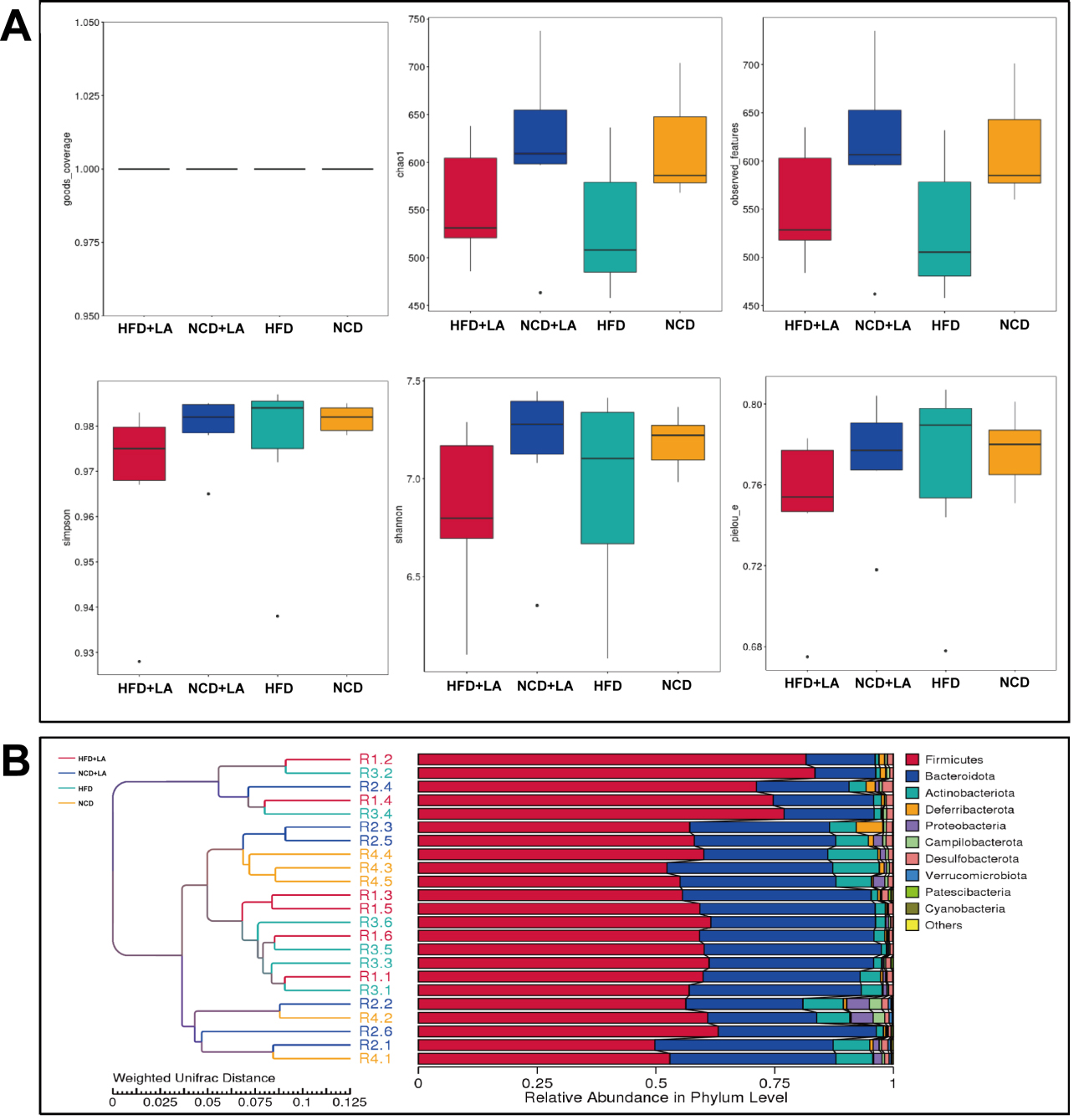

Microbial diversity was evaluated using six indices: goods-coverage, Chao1, observed features, Simpson, Shannon, and Pielou’s evenness [Figure 4A]. Sequencing depth was adequate (goods-coverage ≈ 1.0), ensuring reliable community detection. Richness indicators (Chao1, observed features) ranked as NCD + LA > NCD > HFD + LA > HFD, while Shannon diversity followed NCD + LA > NCD > HFD > HFD + LA. All four groups exhibited high Simpson indices, indicating balanced communities. Rarefaction and species accumulation curves plateaued, confirming sufficient sampling [Supplementary Figure 1A and B]. unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) clustering revealed richness patterns consistent with alpha-diversity results [Supplementary Figure 1C].

Figure 4. Alpha analysis and beta analysis of gut microbiota in mice. A: Goods-coverage, Chao1, observed-features, Simpson, Shannon and Pielou’s E obtained by alpha analysis of gut microbiota in mice; B: UPGMA clustering tree based on weighted Unifrac distance. (n = 5-6 for each group). NCD: Normal chow diet; HFD: high-fat diet; LA: L-arabinose; UPGMA: unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic mean.

Beta-diversity analysis demonstrated that short-term LA treatment did not radically alter microbial structure; principal co-ordinates analysis (PCoA) and UPGMA clustering indicated close similarity between NCD/NCD + LA and HFD/HFD + LA pairs [Supplementary Figure 1D and Figure 4B]. Taken together, these results suggest that LA modestly increases microbial richness and abundance while maintaining overall community stability.

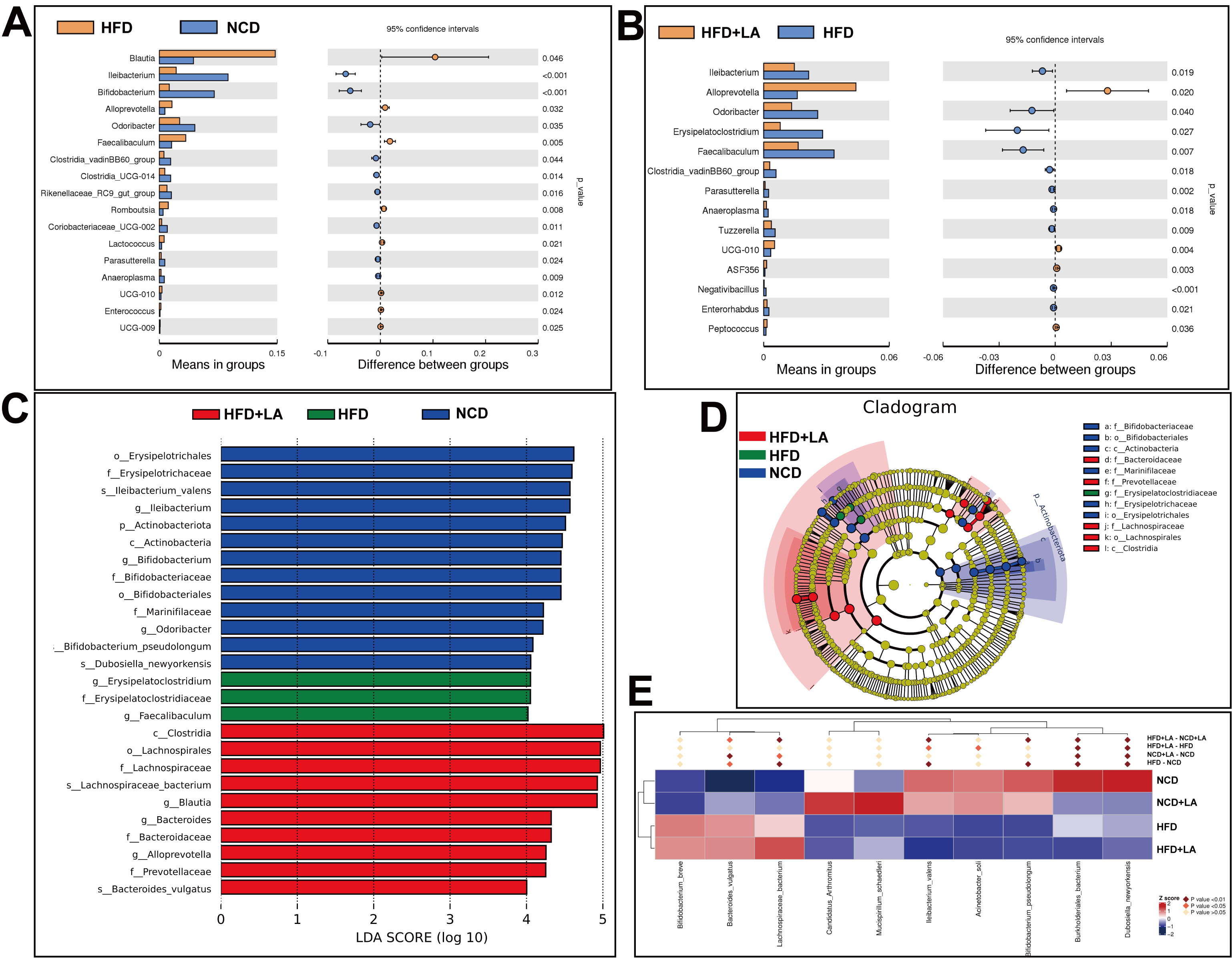

L-arabinose up-regulates short-chain fatty acid metabolism-associated flora

To identify taxa responsive to LA, genus-level t-tests were conducted. Blautia, Alloprevotella, Faecalibaculum, and Romboutsia were elevated in the HFD group compared with NCD controls [Figure 5A]. In contrast, Alloprevotella, UCG-010, and Peptococcus were significantly enriched in HFD + LA mice relative to HFD [Figure 5B]. Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis [linear discriminant analysis (LDA) score > 4.0] revealed overrepresentation of potentially pathogenic Erysipelatoclostridium in HFD mice, whereas the HFD + LA group exhibited enrichment of beneficial SCFA producers, including Lachnospiraceae, Blautia, Bacteroides, and Alloprevotella [Figure 5C and D]. At the species level, Ileibacterium_valens and Dubosiella_newyorkensis - bacteria previously associated with obesity - were significantly reduced following LA supplementation [Figure 5E]. These results indicate that LA fosters microbial taxa linked to SCFA synthesis, thereby contributing to improved lipid metabolism.

Figure 5. Statistical analysis of gut microbiota. (A) t-test between HFD and NCD (P < 0.05); (B) t-test between HFD and HFD + LA (P < 0.05); (C and D) Difference analysis of LEfSe (LDA effect size was used to compare the statistical significance and correlation of the 4 groups of bacteria) with the threshold set to 4; (E) Metastat heatmap. (n = 6 for each group). NCD: Normal chow diet; HFD: high-fat diet; LA: L-arabinose; LEfSe: linear discriminant analysis effect size; LDA: linear discriminant analysis.

Role of L-arabinose on mitochondrial function and hepatic ATF5

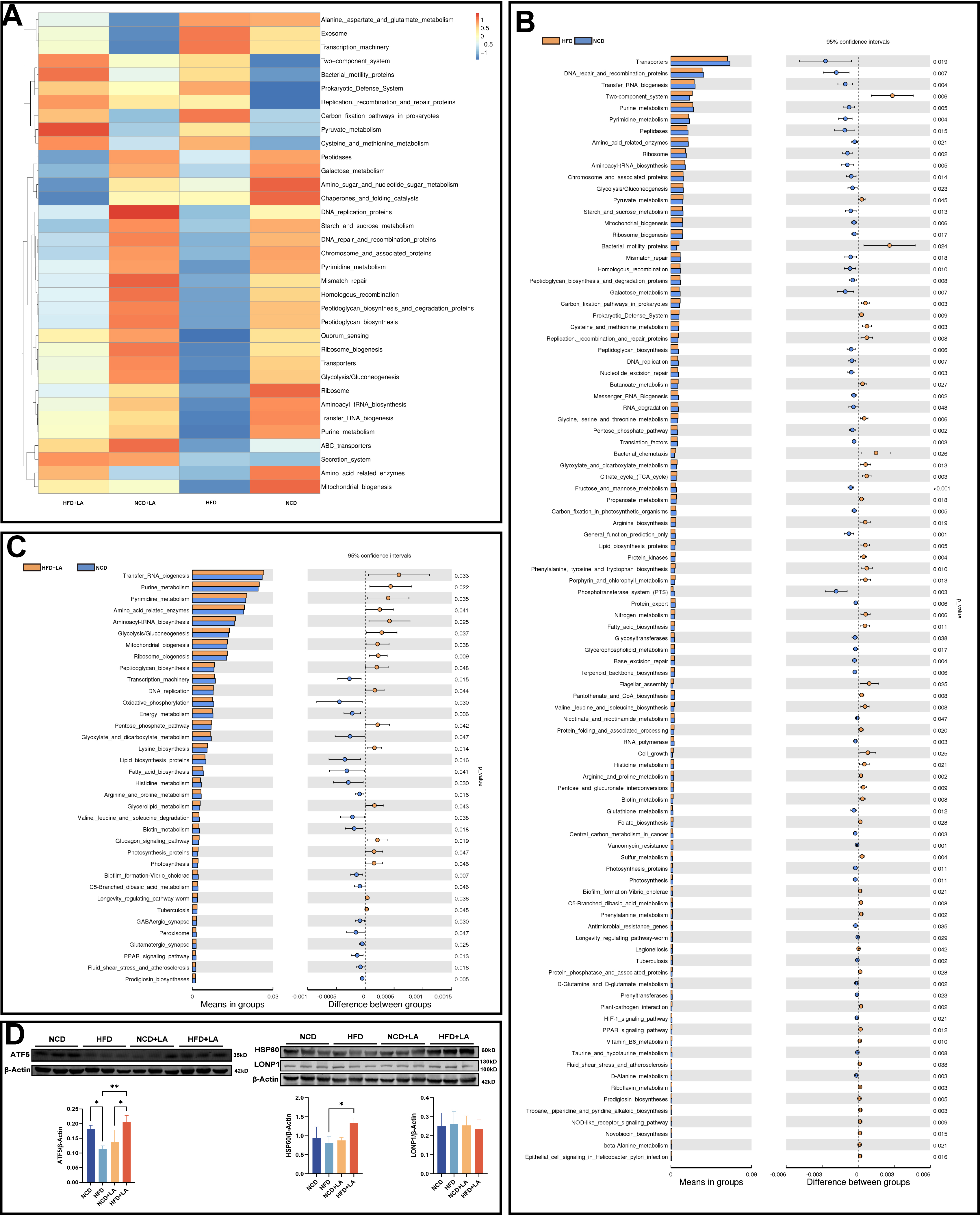

To gain deeper insights into how LA modulates the mouse gut microbiota, we employed the Tax4Fun tool, which operates on the nearest-neighbor principle and relies on minimum 16S rRNA sequence similarity for predicting shifts in microbial communities. Prokaryotic whole-genome 16S rRNA sequences were retrieved from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database and aligned with the SILVA SSU Ref NR database (BLAST bitscore > 1,500) using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool, nucleotide (BLASTN) algorithm to generate correlation matrices. The KEGG database's prokaryotic functional information, annotated by Ultra-fast Protein Classification (UProC) and Protein Annotation Using Domain Architecture (PAUDA), was matched to the SILVA database for functional annotation. Drawing from the database’s functional and abundance data, we selected the top 35 functions at level 3 to construct a heat map [Figure 6A]. To further investigate LA’s role, t-tests were conducted to compare differences between the NCD/HFD groups and the HFD/HFD + LA groups. Notably, mitochondrial biogenesis function was significantly down-regulated in the HFD group relative to the NCD group [Figure 6B], whereas LA significantly elevated it [Figure 6C]. Mitochondrial biogenesis is the process of intracellular mitochondrial generation, including increased mitochondrial number and function, which is closely associated with fatty acid oxidation, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance[21-23]. These results suggest that LA intake induces changes in energy-related microbial functions within the intestinal microenvironment. Given the well-established interactions along the gut-liver axis in the pathogenesis of MASLD[4], functional alterations at the gut level may, in turn, exert downstream effects on hepatic metabolism. Previous work has demonstrated that LA alleviated hepatic lipid metabolism disorders. Combining the results of animal experiments and functional prediction, we hypothesized that LA may alleviate hepatic lipid metabolism disorders in mice by ameliorating the mitochondrial biogenesis dysfunction induced by a HFD. Drawing on this, we used Western blotting to target key proteins for liver mitochondrial function. Interestingly, when we used HSP60 as a mitochondrial internal reference, our results showed that HSP60 protein levels were significantly elevated in the LA-gavage group than in the non-gavage LA group [Figure 6D]. In addition to its frequent role as a mitochondrial internal reference, HSP60 is also closely linked to the UPRmt and mitochondrial stress. It has been demonstrated that HSP60 is a key downstream molecule of ATF5-induced UPRmt and tubulointerstitial injury in diabetic nephropathy[19]. We examined the expression of ATF5 in the liver using WB and found that the ATF5 protein showed an increasing trend in the LA gavage group. From this, we hypothesized that LA may cause an increase in hepatic ATF5 expression by regulating intestinal flora and mitochondrial biogenesis, modulating the UPRmt in hepatocytes and thus alleviating hepatic mitochondrial stress and lipid deposition.

Figure 6. Functional prediction of gut microbiota. (A) Tax4Fun feature annotation clustering heatmap; (B) t-test analysis of functional differences between NCD and HFD groups and (C) between HFD and HFD + LA groups; (D) Western blotting of HSP60, ATF5, and LONP1 in the liver of 4 groups of mice. (****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, and*P < 0.05.). NCD: Normal chow diet; HFD: high-fat diet; LA: L-arabinose; ATF5: transcription factor 5; HSP60: heat shock protein 60; LONP1: Lon protease 1.

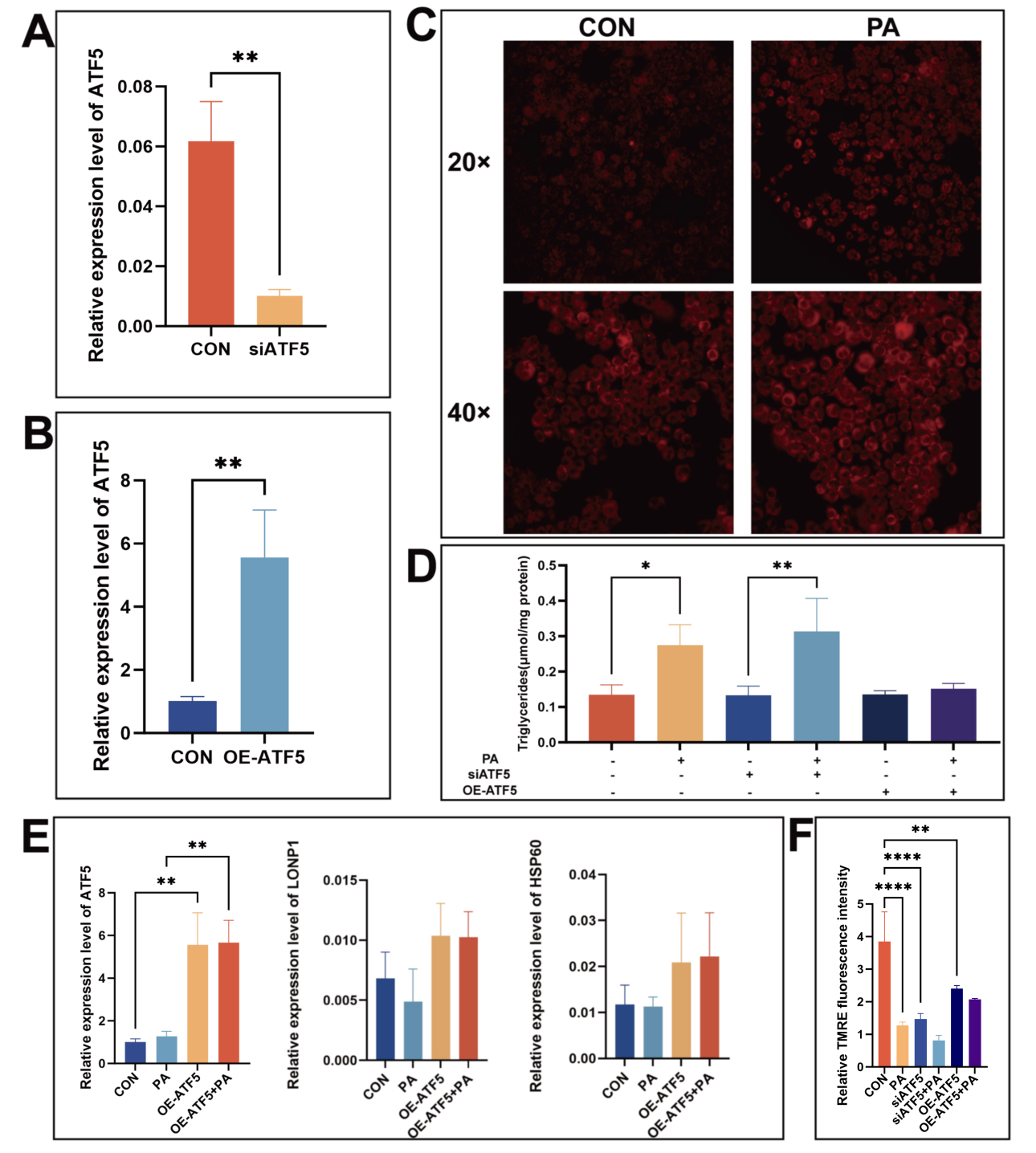

ATF5 alleviates PA-induced mitochondrial stress and lipid deposition in hepatocytes

To examine the role of ATF5 in hepatic lipid metabolism, AML12 cells were treated with PA to simulate a high‑fat dietary environment. An ATF5 knockdown model was established using ATF5‑specific siRNA, while an overexpression model was generated by transfection with an ATF5‑expression plasmid. Effective knockdown and overexpression of ATF5 were confirmed by qPCR. Compared with the control groups, ATF5 mRNA levels were significantly reduced in siRNA‑transfected cells and markedly increased in ATF5‑overexpressing cells [Figure 7A and B]. Nile Red staining revealed that PA treatment induced lipid deposition in AML12 cells [Figure 7C]. Measurement of intracellular TG content showed that ATF5 overexpression alleviated PA-induced TG accumulation [Figure 7D]. HSP60 and LONP1 are key regulators of the UPRmt and are potential transcriptional targets of ATF5[24]. However, our qPCR analysis showed no significant changes in their expression upon ATF5 overexpression [Figure 7E], suggesting that ATF5 may regulate HSP60 and LONP1 through a transcription‑independent mechanism. TMRE fluorescence indicated that PA-treated cells exhibited significantly impaired mitochondrial membrane potential. Under the same PA treatment conditions, ATF5-knockdown cells showed a trend toward membrane potential disruption, whereas ATF5‑overexpressing cells displayed a restorative trend [Figure 7F]. Taken together, these results suggest that ATF5 overexpression attenuates lipid deposition in PA‑exposed AML12 cells.

Figure 7. The effect of ATF5 overexpression or knockdown on AML12 cells. (A) Validation of ATF5 knockdown cell model by qPCR; (B) Validation of ATF5 overexpression cell model by qPCR analysis; (C) Nile Red staining showing PA-induced lipid accumulation in AML12 cells; (D) Measurement of TG content in AML12 cells under different treatments; (E) qPCR analysis of the expression levels of ATF5, HSP60, and LONP1 in the ATF5 overexpression model; (F) TMRE staining relative fluorescence intensity. (****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, and*P < 0.05.) ATF5: Transcription factor 5; siATF5: small interfering RNA targeting transcription factor 5; OE-ATF5: transcription factor 5 overexpression; CON: control; PA: palmitic acid; AML12: alpha mouse liver 12; qPCR: TG: triglyceride; HSP60: heat shock protein 60; LONP1: Lon protease 1.

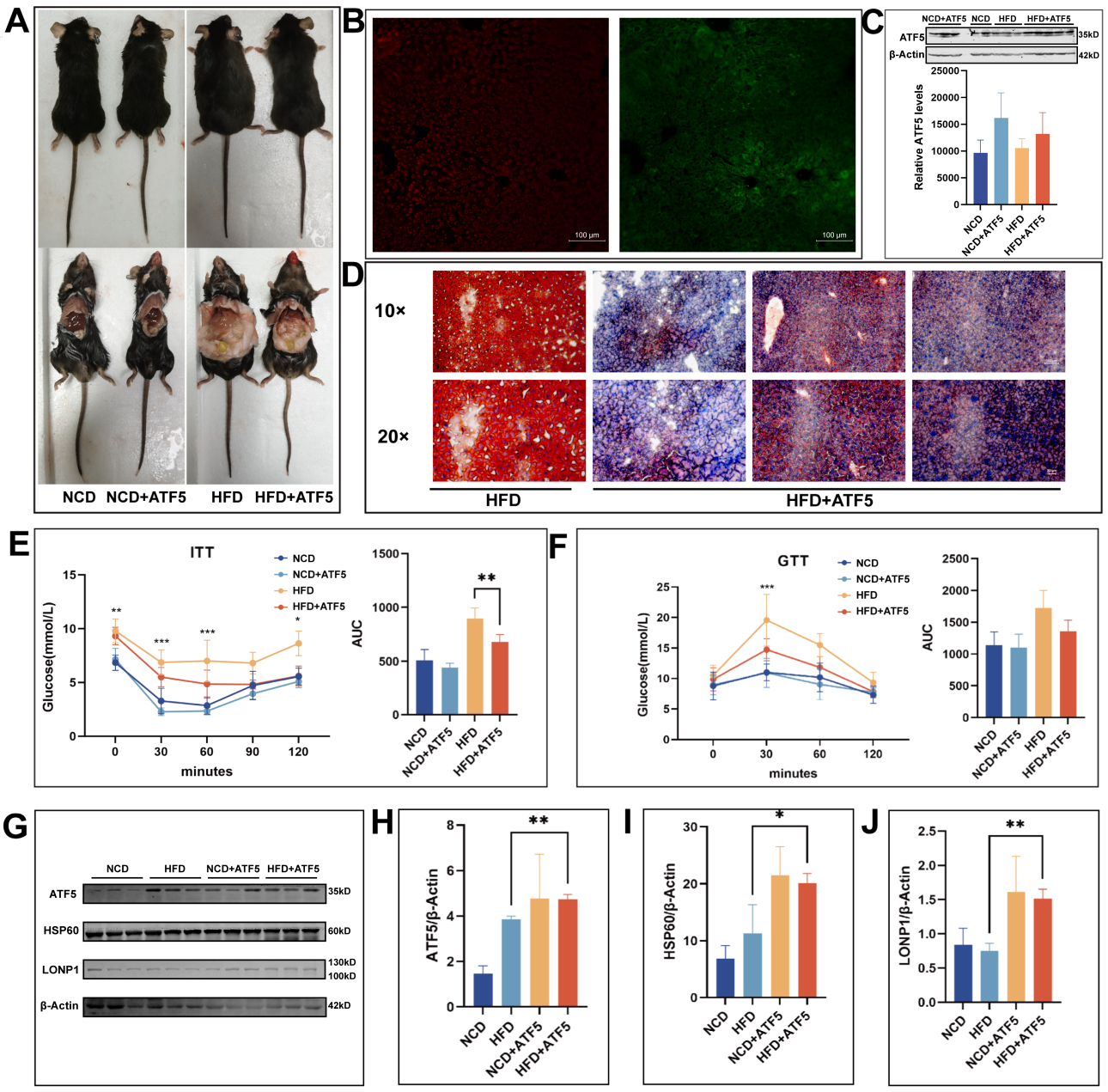

ATF5 overexpression alleviates MASLD via UPRmt activation

To further validate the role of ATF5 in MASLD in vivo, we constructed an ATF5 overexpression mouse model. At the time of sacrifice, histological examination of liver morphology in each group revealed that the livers of mice in the HFD + ATF5 group exhibited reduced volume and diminished lipid deposition compared to those in the HFD group, as shown in Figure 8A. The successful knock-in of the ATF5 gene was confirmed by fluorescence microscopy [Figure 8B], and the high expression of ATF5 in mouse livers was verified by Western blotting [Figure 8C]. Oil red staining of liver sections showed that lipid deposition was significantly reduced in the HFD + ATF5 group relative to the HFD group, suggesting that ATF5 overexpression can significantly alleviate high-fat-diet-induced MASLD [Figure 8D]. A glucose tolerance assay demonstrated that ATF5 overexpression alleviated the decreased glucose metabolism induced by a HFD, while an insulin tolerance assay showed that it alleviated the insulin resistance caused [Figure 8E and F]. Western blotting showed that the expressions of ATF5, HSP60, and LONP1 were increased in the livers of mice in the HFD + ATF5 group [Figure 8G-J], which suggests that the UPRmt was significantly activated in HFD + ATF5. In summary, ATF5 overexpression in the liver can alleviate high-fat-diet-induced MASLD by promoting UPRmt.

Figure 8. Overexpression of ATF5 alleviates MASLD in mice. (A) ATF5 overexpressing mice at sacrifice; (B) ATF5 overexpression of green fluorescence images; (C) Western blotting analysis of ATF5 overexpression efficiency in mouse liver; (D) Oil red staining of frozen liver sections from high-fat-diet-fed mice and ATF5 overexpressing mice; (E) four groups of mice ITT experiment; (F) Four groups of mice GTT experiment; G-J: Western blot bands and quantitative analysis reveal the expression levels of ATF5, HSP60, and LONP1 proteins in the livers of the four groups of mice. (****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, and*P < 0.05.). NCD: Normal chow diet; HFD: high-fat diet; LA: L-arabinose; ATF5: transcription factor 5; HSP60: heat shock protein 60; LONP1: Lon protease 1; AUC: area under curve; ITT: insulin tolerance test; GTT: glucose tolerance test; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we explore the impact of short-term LA application on modulating hepatic lipid metabolism disorders, focusing specifically on the role of intestinal flora and the ATF5 transcription factor. Our results demonstrate that LA administration mitigates the mitochondrial dysfunction induced by a HFD, with a marked elevation in hepatic ATF5 expression. This intervention plays a critical role in alleviating mitochondrial stress in the liver and reducing lipid deposition. Importantly, we identified that LA enhances the relative abundance of beneficial gut microbiota linked to SCFA metabolism, providing a novel mechanism through which LA alleviates hepatic lipid deposition. The molecular basis for these effects involves the ATF5-induced UPRmt, which reduces mitochondrial stress and helps to restore normal lipid metabolism. These findings contribute new perspectives to potential therapeutic approaches for the clinical management of MASLD.

Our study presents novel evidence that short-term LA application not only improves lipid metabolism but also mitigates hepatic lipid deposition in mice. The 16S rRNA sequencing analysis of gut microbiota revealed that LA administration significantly increased microbial diversity and the abundance of beneficial bacterial species, especially those associated with SCFA metabolism. These shifts in the gut microbiome were linked to mitochondrial biogenesis regulation, suggesting a direct connection between gut flora modulation and hepatic metabolic improvement. Further investigation into the molecular mechanisms of LA revealed that its beneficial effects on lipid metabolism were associated with the upregulation of ATF5 expression. As a key regulator of mitochondrial stress response, ATF5 plays a crucial role in UPRmt activation. Our findings further highlight its role in alleviating lipid metabolism disorders by inducing HSP60 and LONP1 expression, two proteins involved in mitochondrial quality control[25]. HSP60 is a molecular chaperone that assists in mitochondrial protein folding, while LONP1 is a protease responsible for degrading misfolded proteins, both of which are critical for maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis and function[26,27].

To further dissect the molecular mechanisms, we employed liver-targeted gene overexpression and RNAi techniques to manipulate ATF5 expression in vivo. Our results confirmed that ATF5 activation induced the UPRmt, leading to HSP60 and LONP1 upregulation and ultimately alleviating hepatic lipid deposition. Interestingly, endogenous UPRmt activation under chronic metabolic stress may be subject to dynamic compensatory regulation[28]. Our findings suggest that ATF5 can, to some extent, reactivate this protective program. Moreover, the regulation of UPRmt by ATF5 in vivo likely relies on organism-level signal integration, which may account for its limited transcriptional effect in vitro and its pronounced functional impact under pathological conditions. This study reveals a novel molecular pathway via which ATF5 regulates mitochondrial stress and lipid metabolism by activating the UPRmt, providing a mechanistic understanding of how LA intervention influences hepatic lipid homeostasis.

In summary, LA simultaneously reshapes gut microbial structure and promotes hepatic mitochondrial proteostasis through the ATF5-UPRmt axis. This dual regulation provides mechanistic insight into how dietary interventions can restore metabolic balance in MASLD. The identification of this gut-mitochondrial pathway offers a promising foundation for developing microbiota-targeted and mitochondrial-directed therapies for metabolic liver disease.

Although this study provides novel evidence that LA ameliorates hepatic lipid accumulation through the gut microbiota-ATF5-UPRmt axis, several important limitations should be acknowledged. Mechanistically, although 16S rRNA sequencing revealed remodeling of the gut microbiota by LA, the lack of direct experimental data - such as isotopic tracing and portal vein metabolite monitoring - prevents definitive discrimination between its direct hepatic actions and indirect microbiota-mediated contributions. Furthermore, without fecal SCFA quantification and microbial transplantation experiments, the functional contribution of specific microbial changes to the observed hepatic benefits requires further validation. At the molecular level, the signaling pathway connecting LA to ATF5 activation remains incompletely elucidated, including the precise mechanism of ATF5 upregulation and the identity of key gut-liver signaling molecules. These limitations highlight valuable directions for future research, including long-term animal studies, integrated multi-omics analyses, and diverse functional validation approaches.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the several collaborators and the Shandong Provincial Key Medical and Health Laboratory of Translational Medicine in Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases who have contributed to the studies. The Graphic Abstract was created using Adobe Illustrator.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: Zhang H, Chen R

Methodology: Zhang H

Software: Wang Y

Validation: Zhang H, Chen R, Zhang W

Formal analysis: Zhang W

Investigation: Ning J

Resources: Wang X

Data curation: Zhao M

Writing - original draft preparation: Zhang H, Chen R

Writing - review and editing: Lin D, Wang X

Visualization: Li Y

Supervision: Lin D, Wang X

Project administration: Lin D, Wang X

Funding acquisition: Lin D, Wang X

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Original data for this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. The 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing data from this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database under accession number PRJNA1244621, titled “16S amplicon of gut microbiota in mice orally administered with L-arabinose.” Readers can publicly access the relevant data in the NCBI database using this accession number.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2022QH231, ZR2025MS1333), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M732137), Medical and Health Technology Project of Shandong Province (202403060206), Technology Project of the Shandong Society of Geriatrics (LKJGG2024Z002), Innovation Project of Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences, and the Youth Science Foundation Program of Shandong First Medical University (XJ20240127).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shandong Institute of Endocrine & Metabolic Diseases (20221102) and conducted according to the criteria outlined in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals”. The AML12 cell line used in this study was obtained from the Shanghai Cell Bank.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Lazarus JV, Newsome PN, Francque SM, Kanwal F, Terrault NA, Rinella ME. Reply: a multi-society Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology. 2024;79:E93-4.

2. Targher G, Byrne CD, Tilg H. MASLD: a systemic metabolic disorder with cardiovascular and malignant complications. Gut. 2024;73:691-702.

3. Mansouri A, Gattolliat CH, Asselah T. Mitochondrial dysfunction and signaling in chronic liver diseases. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:629-47.

4. Aron-Wisnewsky J, Vigliotti C, Witjes J, et al. Gut microbiota and human NAFLD: disentangling microbial signatures from metabolic disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:279-97.

5. de Vos WM, Tilg H, Van Hul M, Cani PD. Gut microbiome and health: mechanistic insights. Gut. 2022;71:1020-32.

6. Min BH, Devi S, Kwon GH, et al. Gut microbiota-derived indole compounds attenuate metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease by improving fat metabolism and inflammation. Gut Microbes. 2024;16:2307568.

7. Forlano R, Martinez-Gili L, Takis P, et al. Disruption of gut barrier integrity and host-microbiome interactions underlie MASLD severity in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. Gut Microbes. 2024;16:2304157.

8. Krog-Mikkelsen I, Hels O, Tetens I, Holst JJ, Andersen JR, Bukhave K. The effects of L-arabinose on intestinal sucrase activity: dose-response studies in vitro and in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:472-8.

9. Osaki S, Kimura T, Sugimoto T, Hizukuri S, Iritani N. L-arabinose feeding prevents increases due to dietary sucrose in lipogenic enzymes and triacylglycerol levels in rats. J Nutr. 2001;131:796-9.

10. Wang Q, Xiong J, He Y, et al. Effect of L-arabinose and lactulose combined with Lactobacillus plantarum on obesity induced by a high-fat diet in mice. Food Funct. 2024;15:5073-87.

11. Shen D, Lu Y, Tian S, et al. Effects of L-arabinose by hypoglycemic and modulating gut microbiome in a high-fat diet- and streptozotocin-induced mouse model of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Food Biochem. 2021;45:e13991.

12. Li X, Cai Z, Liu J, et al. Antiobesity effect of L-arabinose via ameliorating insulin resistance and modulating gut microbiota in obese mice. Nutrition. 2023;111:112041.

13. Xiang S, Ge Y, Zhang Y, et al. L-arabinose exerts probiotic functions by improving gut microbiota and metabolism in vivo and in vitro. J Funct Foods. 2024;113:106047.

14. Juárez-Fernández M, Goikoetxea-Usandizaga N, Porras D, et al. Enhanced mitochondrial activity reshapes a gut microbiota profile that delays NASH progression. Hepatology. 2023;77:1654-69.

15. Zhu JH, Ouyang SX, Zhang GY, et al. GSDME promotes MASLD by regulating pyroptosis, Drp1 citrullination-dependent mitochondrial dynamic, and energy balance in intestine and liver. Cell Death Differ. 2024;31:1467-86.

16. Zhao Y, Zhou Y, Wang D, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in metabolic dysfunction fatty liver disease (MAFLD). Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24.

17. LeFort KR, Rungratanawanich W, Song BJ. Contributing roles of mitochondrial dysfunction and hepatocyte apoptosis in liver diseases through oxidative stress, post-translational modifications, inflammation, and intestinal barrier dysfunction. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2024;81:34.

18. Hauffe R, Rath M, Schell M, et al. HSP60 reduction protects against diet-induced obesity by modulating energy metabolism in adipose tissue. Mol Metab. 2021;53:101276.

19. Liu Y, Zhang L, Zhang S, et al. ATF5 regulates tubulointerstitial injury in diabetic kidney disease via mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Mol Med. 2023;29:57.

20. Li Y, Pan H, Liu JX, et al. l-arabinose inhibits colitis by modulating gut microbiota in mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2019;67:13299-306.

21. Wang YP, Sharda A, Xu SN, et al. Malic enzyme 2 connects the Krebs cycle intermediate fumarate to mitochondrial biogenesis. Cell Metab. 2021;33:1027-1041.e8.

22. Bouchez C, Devin A. Mitochondrial biogenesis and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS): a complex relationship regulated by the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway. Cells. 2019;8:287.

23. Ruegsegger GN, Creo AL, Cortes TM, Dasari S, Nair KS. Altered mitochondrial function in insulin-deficient and insulin-resistant states. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:3671-81.

24. Fiorese CJ, Schulz AM, Lin YF, Rosin N, Pellegrino MW, Haynes CM. The transcription factor ATF5 mediates a mammalian mitochondrial UPR. Curr Biol. 2016;26:2037-43.

25. Zhou Z, Fan Y, Zong R, Tan K. The mitochondrial unfolded protein response: A multitasking giant in the fight against human diseases. Ageing Res Rev. 2022;81:101702.

26. Lin YF, Schulz AM, Pellegrino MW, Lu Y, Shaham S, Haynes CM. Maintenance and propagation of a deleterious mitochondrial genome by the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Nature. 2016;533:416-9.

27. Shin CS, Meng S, Garbis SD, et al. LONP1 and mtHSP70 cooperate to promote mitochondrial protein folding. Nat Commun. 2021;12:265.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].