Beyond the liver: targeting the hepatic microenvironment and multi-organ networks for innovative MASH therapy

Abstract

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) represents a progressive liver disease of a rapidly increasing global prevalence, driven by intricate pathophysiological interactions within the hepatic microenvironment and systemic crosstalk between the liver and peripheral organs. This review delineates the dynamic roles of key hepatic effector cells, including hepatocytes, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells, Kupffer cells, and hepatic stellate cells, in disease initiation and progression, highlighting how their dysregulated intercellular communication through soluble mediators and extracellular vesicles perpetuates a vicious cycle of lipotoxicity, inflammation, and fibrosis. Furthermore, we expound on the critical involvement of extrahepatic organ networks, specifically the gut-liver, adipose-liver, and muscle-liver axes, in exacerbating hepatic metabolic dysregulation via microbial dysbiosis, aberrant adipokine secretion, and myokine imbalances. The repeated failure of highly selective, single-target therapies in clinical trials underscores the multifactorial nature of MASH pathogenesis and necessitates a paradigm shift in therapeutic strategies. We propose that future innovations should embrace two novel perspectives: first, the development of multi-target agents capable of simultaneously rectifying aberrant multicellular crosstalk within the hepatic microenvironment; and second, the modulation of dynamic interplay between the liver and other organs to restore systemic metabolic homeostasis. Ultimately, integrating such multi-target approaches with precision medicine tailored to individual genetic and phenotypic profiles holds the key to curbing the growing MASH epidemic.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), previously known as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), is a progressive liver disease characterized by hepatic steatosis, chronic inflammation, and fibrosis, primarily driven by metabolic dysregulation such as obesity, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia[1,2]. With the global surge in obesity and metabolic syndrome[3,4], MASH has emerged as a leading cause of chronic liver disease[5], affecting an estimated 1.5%-6.5% of the global population[6] and disproportionately impacting regions such as North America (5%-7%) and the Middle East (4%-5%)[7]. Its prevalence is projected to increase by approximately 63% by 2030[8,9], fueled by sedentary lifestyles and an aging population[10]. High-risk groups include individuals with type 2 diabetes (T2D) (60%-70% prevalence of hepatic steatosis, with 20%-30% progressing to MASH) and those with obesity (70%-90% prevalence of hepatic steatosis, with 20%-40% developing advanced fibrosis)[11-13]. Clinically, MASH is associated with severe morbidity, with 20%-30% of patients progressing to cirrhosis within 7-15 years and a 10%-20% 10-year risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[14], accounting for 10%-20% of HCC cases in Western countries[15,16].

The pathogenesis of MASH is best explained by a “multiple-hit” model[17], in which insulin resistance and central obesity drive excessive free fatty acid (FFA) flux to the liver[18], leading to lipid overload, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress[19,20], and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress[21]. It is notable that the development and progression of MASH exhibit substantial heterogeneity, which is accompanied by a range of extrahepatic complications. This heterogeneity poses significant challenges for the clinical management and treatment of MASH[22]. Individuals homozygous for the patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3) Ile148Met variant (polymorphic variant rs738409) display impaired hepatic mitochondrial function, reduced de novo lipogenesis (DNL), and altered carbon metabolic pathways[23]. This genetically driven form of MASH does not increase the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD); Mendelian randomization studies have confirmed no causal relationship between PNPLA3 rs738409 G-linked metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and ischemic heart disease. Moreover, both the PNPLA3 rs738409 G allele and the TM6SF2 (transmembrane 6 superfamily 2) rs58542926 T allele - another variant tied to MASLD risk - are linked to higher incidence of T2D but lower triglyceride and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels, conferring a protective effect against coronary artery disease[24]. Proposed underlying mechanisms, including reduced enzymatic activity of PNPLA3 and a metabolically more benign hepatic lipid profile, have been investigated in previous studies. Therefore, genetic heterogeneity represents a critical factor to consider in the context of precision medicine. Integrating the concepts of the multiple-hit hypothesis and inter-individual heterogeneity, we propose that MASH is driven by the combined dysregulation of the hepatic microenvironment and crosstalk between the liver and other organs or systems.

Current clinical management of MASH relies on three core pillars: lifestyle modifications (calorie restriction, exercise) as first-line therapy; the only approved pharmacotherapy thyroid hormone receptor β agonists for fibrosis improvement; and non-invasive tests (FIB-4, liver stiffness measurement) complementing liver biopsy for disease staging. However, limitations remain, including variable patient response, the challenge of sustained weight loss, side effects, and the need for better non-invasive monitoring tools. The future lies in combination therapies targeting different pathways and personalized medicine based on disease drivers.

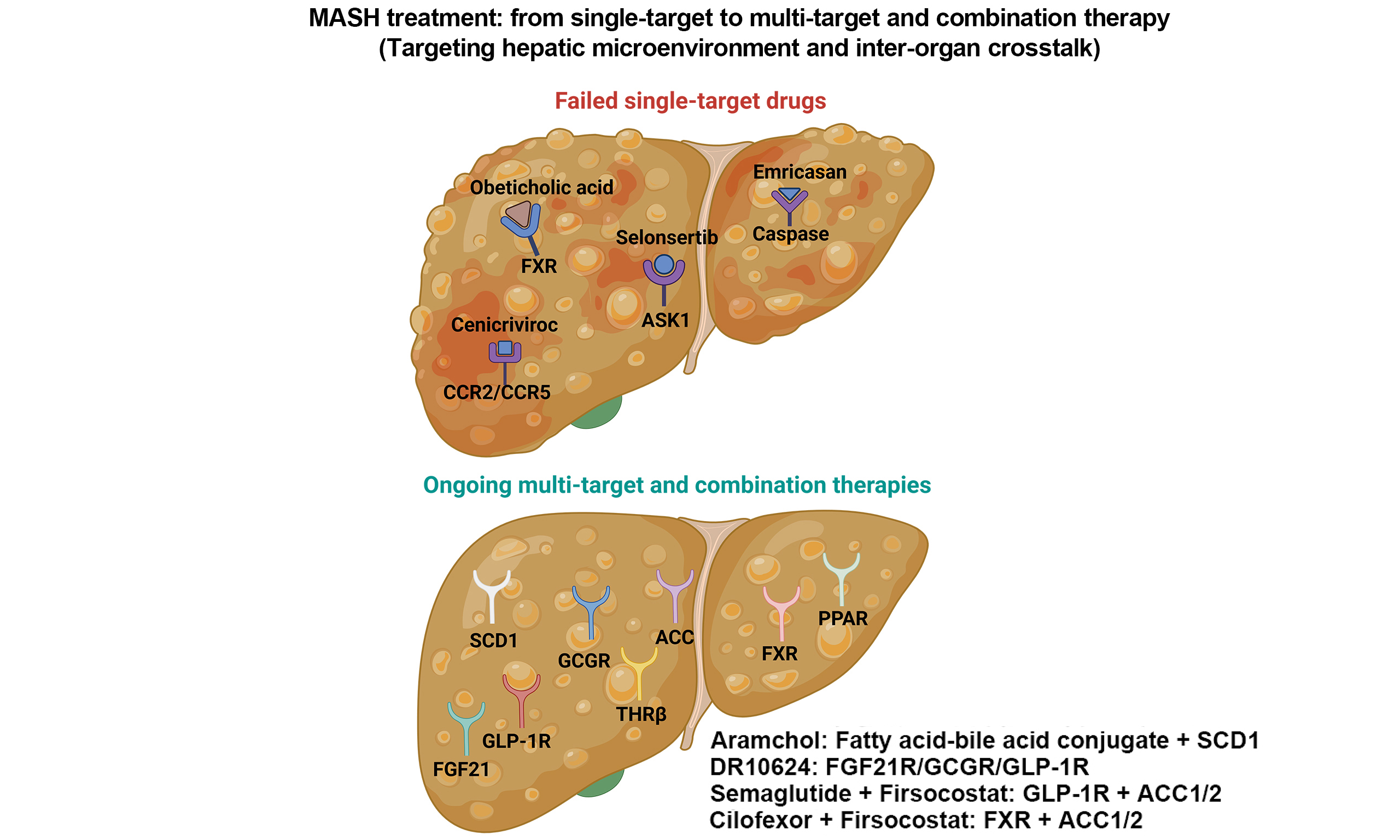

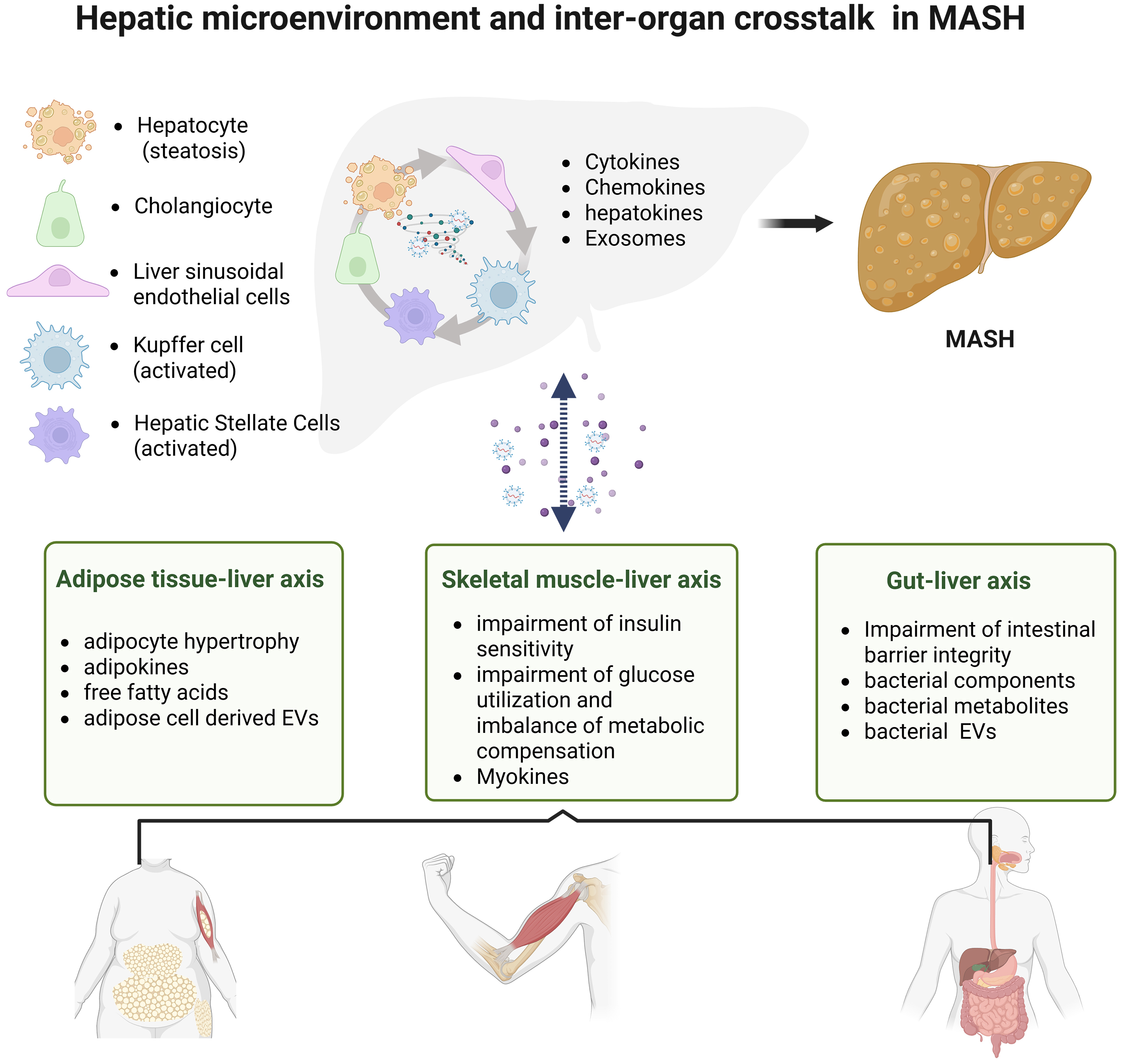

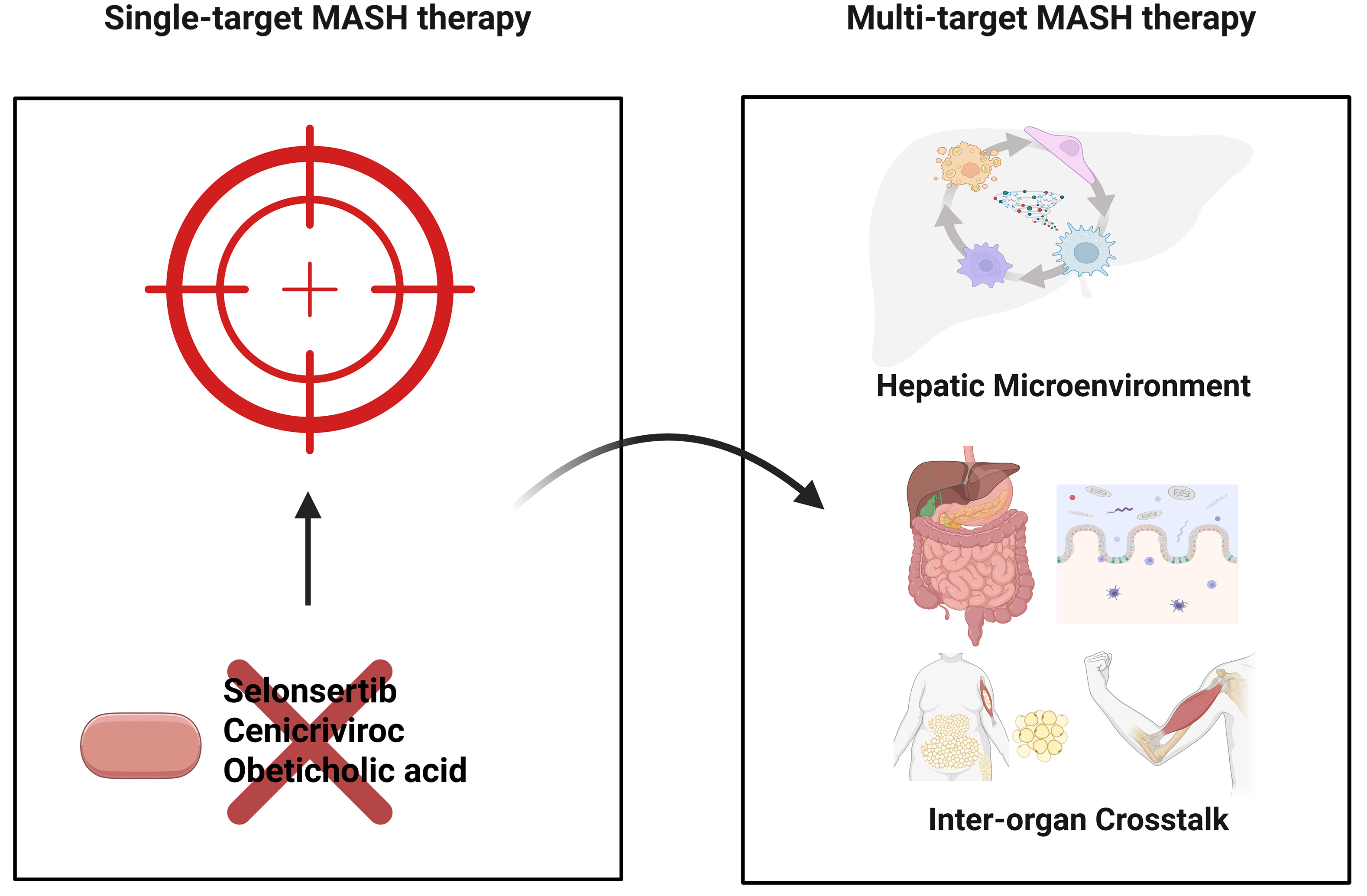

This review summarizes the dynamic changes in the hepatic microenvironment during the development of MASH, including the alterations of key effector cells [hepatocytes, cholangiocytes, sinusoidal endothelial cells, Kupffer cells (KCs), and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs)] in the initiation and progression of MASH, as well as their roles in mediating intercellular communication through diverse secretory products. Furthermore, recognizing that MASH is a chronic systemic disorder affecting the entire body, we emphasize that therapeutic strategies for MASH should not only target the hepatic microenvironment but also consider the dynamic crosstalk between the liver and other organs [Figure 1]. Accordingly, this review proposes novel perspectives for MASH drug discovery: first, the development of multi-target drugs at the multicellular level is essential for further MASH treatment; and second, drugs designed by regulating the interactions between multiple organs are more effective in alleviating MASH and its complications. Finally, precision medicine tailored to genetic and phenotypic profiles may represent a pivotal step toward curbing the global MASH epidemic.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of hepatic microenvironment and inter-organ crosstalk in MASH. Created in BioRender. Fu R (2025) https://BioRender.com/oygjm06. MASH: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; EVs: extracellular vehicles.

HEPATIC MICROENVIRONMENT AND MASH

In recent years, accumulating evidence has indicated that the hepatic microenvironment plays a pivotal role in the pathophysiological processes underlying MASH, MASH-induced liver fibrosis, and HCC formation[25]. The hepatic microenvironment is shaped by complex interactions among hepatocytes, cholangiocytes, sinusoidal endothelial cells, KCs, and HSCs[26]. These cell populations engage in dynamic crosstalk through direct cell-cell contact, soluble mediators (such as cytokines, chemokines, and adipokines), and extracellular vehicles (EVs), establishing a self-perpetuating cycle of metabolic dysregulation, immune activation, and fibrotic remodeling[27,28].

A comprehensive understanding of the hepatic microenvironment can facilitate the precise design of therapeutic agents for different stages of MASH and enable individualized precision therapies based on the specific conditions of different patients. Moreover, developing multi-target drugs aimed at restoring normal multicellular crosstalk in the hepatic microenvironment represents a more suitable strategy for MASH treatment.

Hepatocytes in MASH: guardians of metabolism and drivers of disease progression

Hepatocytes, which constitute approximately 70%-80% of the liver’s cellular mass, are the principal parenchymal cells responsible for maintaining systemic metabolic homeostasis, detoxification, and protein synthesis[29]. Under normal conditions, hepatocytes tightly balance lipogenesis and lipid oxidation. In MASH, however, hepatocytes undergo a dynamic process that progresses from metabolic imbalance (steatosis) to cellular stress and damage (lipotoxicity), leading to cell death and senescence, and ultimately culminating in regenerative failure and fibrosis. Understanding this complex, dynamic process is essential for developing therapeutic strategies that target different disease stages, including hepatocyte protection, clearance of senescent cells, and inhibition of cell death[30].

Hepatocyte injury and immune response in MASH

Mitochondrial dysfunction caused by lipotoxicity in hepatocytes generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), which oxidize hepatic lipids to produce reactive aldehydes such as 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) and malondialdehyde (MDA). These lipid peroxidation products act as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs)[31], activating KCs and recruiting monocytes through chemokines [CC motif ligand 2 (CCL2) and 5 (CCL5)] and adhesion molecules [intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1)][32]. Hepatocyte-derived EVs enriched with miR-122 and miR-34 further amplify inflammation by priming macrophages toward a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype[33]. Lipotoxic hepatocytes also release EVs containing miR-192-5p, inducing macrophage differentiation into the profibrotic M1 phenotype[34]. In addition to microRNAs (miRNAs), hepatocyte-derived EVs regulate immune cell activity via the lipids and proteins they carry. In MASH, hepatocyte-derived EVs enriched in Sphingosine 1-Phosphate (S1P) mediate sustained, directional macrophage chemotaxis through the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-1 (S1P1)[35]. Lipotoxic hepatocyte-derived EVs that are rich in active integrin β1 promote monocyte adhesion and hepatic inflammation in a mouse model of MASH[36]. Activation of inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α) in hepatocytes enhances the transcription of serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT) genes via X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1), inducing ceramide synthesis and its release in EVs. These EVs attract monocyte-derived macrophages (MoMFs) to the liver, driving inflammation and tissue damage in diet-induced steatohepatitis[37]. Moreover, toxic lipids stimulate hepatocytes to release EVs enriched with tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) protein via activation of death receptor 5 (DR5), which can activate the inflammatory phenotype of macrophages[38].

Hepatocyte injury and fibrosis in MASH

Hepatocytes also contribute to fibrosis through direct trans-differentiation into a profibrotic phenotype[39]. During chronic liver injury, a subset of hepatocytes undergoes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), characterized by the loss of E-cadherin and the acquisition of vimentin and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) expression. These EMT-derived cells synthesize collagen types I and III, directly facilitating extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition. Additionally, apoptotic hepatocytes generate apoptotic bodies enriched with sonic hedgehog (SHH), which activate HSCs via smoothened (SMO)-dependent signaling, further exacerbating fibrosis[40]. EVs derived from human hepatic stem cells can regulate HSC activation[41]. Similarly, EVs derived from steatotic hepatocytes influence the behavior, phenotype, and expression of remodeling markers in HSCs, as well as guide their directional migration[42]. MiR-122, the most abundant hepatocyte-specific miRNA, is elevated in circulation during MASH and promotes fibrogenesis by suppressing peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ in HSCs, enhancing collagen synthesis[43,44]. Moreover, hepatocytes secrete EVs enriched with mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease 1 (MASP1), which activates HSCs via the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-activating transcription factor 2 (ATF2) signaling pathway, thereby promoting the progression of hepatic fibrosis[45].

Hepatocyte senescence in MASH

Hepatocytes, the primary functional cells of the liver, undergo senescence in response to lipid accumulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and ER stress[46]. Senescent hepatocytes serve as key drivers of hepatic inflammation by activating intrahepatic immune cells (such as KCs) and HSCs through the secretion of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) proteins. This sustained, low-grade chronic inflammation in the liver represents a critical step in the progression from simple fatty liver [metabolic-associated fatty liver (MAFL)] to steatohepatitis [metabolic-associated steatohepatitis (MASH)][47]. Specifically, senescent hepatocytes secrete chemokines such as CCL2, which recruit pro-inflammatory immune cells to the liver and exacerbate tissue damage. They also secrete plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), which not only impairs fibrinolysis but also promotes fibrosis by inhibiting the activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)[48].

Current therapeutic strategies targeting hepatocytes for MASH aim to restore metabolic balance and mitigate lipotoxicity. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) agonists (e.g., pemafibrate) enhance fatty acid oxidation[49], whereas acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) inhibitors (e.g., firsocostat) reduce DNL, although compensatory hypertriglyceridemia remains a clinical concern[50,51]. Inhibition of Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase 1/2 (ACC1/2) can reduce fatty acid synthesis and promote fatty acid oxidation, thereby lowering hepatic fat contents[52]. However, it potentially causes adverse effects such as hypertriglyceridemia and thrombocytopenia. Consequently, ACC inhibitors are mostly pursued within combination therapy regimens, such as Firsocostat[53] with the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonist Cilofexor[54]. Thyroid hormone receptor β (THRβ) agonists, including resmetirom, promote mitochondrial biogenesis and lipid clearance, demonstrating efficacy in clinical trials and are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)[55,56]. However, limited response rate and side effects continue to restrict therapeutic success. Emricasan is an oral, irreversible pan-caspase inhibitor that inhibits hepatocyte apoptosis. However, its phase II clinical trial was terminated because it failed to translate into improvements in any clinical endpoints[57]. Emerging approaches including gene therapy to silence sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) and enhance Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1) expression offer new promise for correcting hepatocellular lipid metabolism[58]. Nonetheless, hepatocyte-directed therapies must balance efficacy with systemic metabolic effects, as global suppression of lipogenesis may disrupt extrahepatic lipid homeostasis[59].

Cholangiocytes in MASH

Cholangiocytes line the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts and are involved in bile formation and systemic homeostasis. Cholangiocyte damage occurs in a variety of human diseases, collectively termed cholangiopathies, which often progress to end-stage liver failure[60].

Cholangiocytes in transdifferentiation and liver regeneration

During the development and progression of MASH, stimuli from the hepatic microenvironment can induce cholangiocyte transdifferentiation into hepatocytes, thereby contributing to hepatocyte regeneration. Recent studies using intrahepatic cholangiocyte organoids derived from patients with end-stage MASH revealed that activation of the transcription factor hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 gamma (HNF4G) in cholangiocytes is essential for their transdifferentiation into biphenotypic cells that co-express both cholangiocyte and hepatocyte markers. These observations suggest that regulating cholangiocyte transdifferentiation may play a vital role in managing liver diseases, including MASH[61].

The role of cholangiocytes in MASH stages

Beyond their regenerative function, cholangiocytes themselves play significant roles in the initiation, progression, and advanced stages of MASH through multiple mechanisms.

Metabolic abnormalities trigger cholangiocyte dysfunction during the initiation stage of MASH. Obesity and a high-sugar, high-fat diet induce insulin resistance, leading to excessive hepatic fat accumulation. Insulin resistance inhibits the function of the “sodium-taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide (NTCP)” and “bile salt export pump (BSEP)” on the cholangiocyte surface[62,63]. Consequently, bile acid uptake and secretion are impaired, leading to “intrahepatic bile acid accumulation”. This accumulation directly damages hepatocytes and indirectly exacerbates liver injury by promoting intestinal microbiota dysbiosis and disrupting gut-liver axis homeostasis[63]. In the progression stage of MASH, cholangiocytes drive hepatic inflammatory response. Damaged cholangiocytes secrete chemokines such as CCL2, CCL5, and chemokine (CXC motif) ligand (CXCL)1, which facilitate macrophage recruitment and drive the accumulation of CD11b/F4/80+CCR2high (CCR2 = C-C chemokine receptor type 2)/lymphocyte antigen 6 complexhigh inflammatory monocytes in the liver[64].

Currently, selectively targeting molecules that are highly expressed or functionally critical in cholangiocytes to directly regulate their activation, proliferation, senescence, or secretory behavior offers a promising avenue for MASH intervention. The apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter (ASBT, also known as ileal bile acid transporter (IBAT)) is predominantly localized on the apical membrane of cholangiocytes within small bile ducts[65]. Inhibition of ASBT in MASH reduces the uptake of cytotoxic bile acids, thereby alleviating cholangiocyte stress and damage[66]. Currently, ASBT inhibitors such as maralixibat[67] and odevixibat[68] have been approved for the treatment of cholestatic liver diseases including Alagille syndrome and progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC). The Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway, a key regulator of cholangiocyte proliferation and differentiation[69], becomes abnormally activated in MASH, resulting in excessive cholangiocyte response and pathological expansion[70]. Pharmacological inhibition of the Hh pathway using SMO inhibitors such as GDC-0449 (vismodegib)[71] and glasdegib[72] has demonstrated efficacy in preclinical models, attenuating both ductular reactions and hepatic fibrosis. Furthermore, advances in human cholangiocyte organoid technology provide a powerful platform for developing personalized therapies and evaluating biliary toxicity, thereby enhancing the success rate of MASH drug development[73].

Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells in MASH: a portal for substance exchange and maintenance of the hepatic microenvironment

Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) are highly specialized endothelial cells lining the inner surface of hepatic sinusoids and account for approximately 40% of the liver’s non-parenchymal cell population. They serve as critical “gateway” cells for substance exchange, immune regulation, and maintenance for the microenvironment between the liver and bloodstream[74].

Capillarization of LSECs and hepatocellular ballooning in MASH

During the development and progression of MASH, LSECs undergo capillarization, which is considered an early hallmark of the disease. This process promotes MASH progression through signaling pathways such as Notch-eNOS-nitric oxide (NO) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB)[75]. Specifically, a metabolically disturbed environment (e.g., high fat and high glucose) activates oxidative stress pathways [e.g., nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase] and inflammatory signals (e.g., NF-κB) in LSECs, leading to a reduction in the number and diameter of fenestrae. At the same time, LSECs synthesize large amounts of basement membrane components, including collagen IV, forming a continuous barrier[76]. This structural change impairs the efficient uptake of blood lipids by hepatocytes, thereby exacerbating hepatic steatosis. The formation of the basement membrane further hinders substance exchange between hepatocytes and blood, resulting in the accumulation of metabolic waste in hepatocytes and ultimately inducing hepatocellular injury (ballooning degeneration)[77].

LSECs and immune response in MASH

As “immune sentinels” of the liver, LSECs can recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and DAMPs, initiating immune responses by expressing receptors such as Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)[78]. Metabolic disorders stimulate LSECs to secrete chemokines (e.g., CCL2, CXCL1, and CXCL8), which recruit circulating monocytes (that differentiate into liver macrophages) and neutrophils to infiltrate the hepatic parenchyma. These immune cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6, forming an “inflammatory cascade”[79]. Lipotoxic stress also promotes the expression of VCAM-1 in LSECs through the mixed-lineage kinase 3 (MLK3) signaling pathway, facilitating monocyte adhesion to LSECs[80].

LSEC and HSC activation in MASH

LSECs can regulate hepatocyte regeneration and HSCs quiescence by secreting angiocrine factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and nitric oxide[80]. Protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 (POFUT1) expressed in endothelial cells regulates fibrinogen expression in LSECs via the Notch/HES1 (hairy and enhancer of split 1)/STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) signaling axis, thereby activating HSCs through paracrine signaling and exacerbating deleterious liver fibrosis[81]. In MASH, LSEC dysfunction promotes HSC activation through increased endothelin-1 (ET-1) and decreased angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1)[82]. Chronic MASH-associated transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) overexpression induces LSEC capillarization via miR-21-mediated suppression of Krev Interaction Trapped 1 (KRIT1), a key protein maintaining endothelial integrity[83].

LSECs act as “guardians” of hepatic homeostasis by coordinating the integrity of the sinusoidal microenvironment, metabolic exchange, and immune regulation. In MASH, however, pathological changes in LSECs, such as capillarization, dysregulated immune response, and aberrant interaction with HSCs, drive steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis, representing a central mechanism in MASH progression. Therefore, targeted restoration of LSEC structure and function (e.g., fenestrae repair and inhibition of capillarization) may emerge as a novel therapeutic strategy for MASH.

Currently, therapeutic regimens targeting LSECs in MASH primarily aim to reverse capillarization and restore fenestrae structure and function, though most of these drugs remain in the preclinical phase. Researchers are striving to repair LSEC function by inhibiting targets such as Mer tyrosine kinase (Mertk)[84] and sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 3 (SMPD3)[85] or by using advanced delivery technologies such as engineered exosomes. Given the complexity of MASH, future LSEC-targeted therapies will likely need to be combined with agents that modulate hepatocellular metabolism, inflammation, and HSC activation to achieve synergistic therapeutic efficacy.

Kupffer cells in MASH: orchestrators of immunity and catalysts of hepatic inflammation

KCs, liver-resident macrophages derived from embryonic hematopoietic progenitors, reside in the hepatic sinusoids and account for approximately 15% of total liver cells. Together with recruited MoMFs, KCs play central roles in the development and progression of MASH by regulating inflammatory responses, lipotoxicity responses, fibrotic processes, and metabolic homeostasis, thereby contributing to the entire disease course, from steatosis to liver cirrhosis[86,87].

During the MASH initiation stage, hepatocytes develop steatosis, and macrophages sense lipotoxic signals, activating KCs toward pro-inflammatory M1 type via TLR4/CD14, scavenger receptor class A member 1 (SR-A1)/CD36, and other pathways[88-90]. In the progression stage, hepatocellular ballooning and necrosis release DAMPs [e.g., high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP)] to hyperactivate macrophages. These macrophages secrete chemokines (e.g., CCL2 and CCL5) to recruit Ly6C+ monocytes, which differentiate into MoMFs with a reduced capacity to promote hepatic triglyceride storage[91,92]. MoMFs and residual KCs form inflammatory clusters and secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, exacerbating liver injury[93]. In addition, macrophage-derived Neutrophil Cytosolic Factor 1 (NCF1) induces iron overload and ferroptosis in KCs, further accelerating MoMF infiltration and disease progression[94]. Furthermore, macrophages activate intrahepatic CD4+ T cells [e.g., T helper type 1 (Th1) and 17 (Th17)], creating a “macrophage-T cell” inflammatory loop that drives chronic inflammation. In the exacerbation stage, persistent inflammation and hepatocellular injury trigger fibrosis, with macrophages activating HSCs[95]: M1 predominates early, then shifts to M2 (excessive M2 promotes fibrosis), and M2 KCs eliminate M1 via interleukin (IL)-10/arginase[96]. Galectin-12 regulates KC polarization, preventing metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) progression and modulating fibrosis via the suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3)-signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6)-TGF-β1 pathway[97]. TREM2+ macrophages, characterized by high CCR2/CX3C motif chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1) expression, correlate with the degree of MASH fibrosis[98,99].

KCs can also enter a senescent state under sustained activation. Their SASP further distorts immune responses and acts as an amplifier of inflammation, by secreting high levels of potent pro-inflammatory factors, including TNF-α and IL-1β[100]. These factors induce hepatocyte apoptosis or necrosis, damage hepatic parenchyma, and activate HSCs, bridging inflammation and fibrosis. Senescent immune cells have reduced ability to clear pathogens and apoptotic cells, yet their SASP continues to release inflammatory signals, which results in the failure of effective resolution of inflammation.

Throughout the entire process of MASH, KCs participate in disease progression, from steatosis to fibrosis, by sensing lipotoxic signals, amplifying inflammatory responses, driving HSC activation, and mediating metabolic-immune crosstalk. Their functional plasticity (M1/M2 polarization) and metabolic dependency make them important therapeutic targets[101,102], such as TLR4 inhibitors, NOD-like receptor (NLR) family, pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome antagonists, and macrophage depletors. A deeper understanding of macrophage dynamics at different disease stages may provide new insights for precise intervention in MASH. A large number of drugs have targeted the hepatic immune system to improve MASH by modulating KC activation and monocyte infiltration. For example, the CCR2/CCR5 antagonist cenicriviroc (CVC) was developed to block CCR2-mediated recruitment of inflammatory monocytes (which differentiate into pro-inflammatory macrophages) and CCR5-mediated activation and migration of T cells and macrophages[103]. Theoretically, by blocking these two receptors, CVC could significantly reduce the infiltration of inflammatory cells in the liver, thereby alleviating inflammation and indirectly exerting anti-fibrotic effects. However, a phase III clinical trial failed to meet its primary endpoint[104], highlighting that targeting a single target is insufficient to resolve the complex inflammatory response in the hepatic microenvironment or address systemic metabolic abnormalities.

Hepatic stellate cells in MASH: from quiescence to fibrogenic activation

HSCs, comprising approximately 5%-8% of liver cells, are perisinusoidal mesenchymal cells residing in the space of Disse[105]. They closely interact with hepatocytes, sinusoidal endothelial cells, and KCs[106]. The balance between quiescent and activated HSCs profoundly influences MASH outcomes. In their quiescent state, HSCs contain cytoplasmic lipid droplets rich in retinyl esters (vitamin A), serving as metabolic reservoirs and maintaining retinoid homeostasis. Quiescent HSCs also produce hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) to support parenchymal cell regeneration[107]. Upon liver injury, such as chronic metabolic stress in MASH, HSCs transdifferentiate into myofibroblast-like cells, driving fibrosis via excessive ECM deposition[108]. This activation process is central to MASH progression[109], as it bridges hepatic metabolic dysfunction and structural remodeling, eventually leading to cirrhosis and HCC[110].

HSC activation and MASH

HSC activation is a multi-step process initiated by paracrine and autocrine signals from injured hepatocytes, immune cells, and altered ECM components[111]. In the early stage of MASH, transient HSC activation may be reparative, involving the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10) and MMPs to resolve minor injury. Persistent metabolic insults, however, convert this adaptive response into maladaptive fibrosis. Once activated, HSCs lose their vitamin A stores, proliferate rapidly, and acquire a contractile phenotype marked by α-SMA expression[112]. They drive ECM deposition and interact with immune cells to perpetuate inflammation. For example, HSCs express chemokines (CXCL1, CCL2) to recruit monocytes and neutrophils[113] and present antigens via MHC class II molecules to activate CD4+ T cells, fostering a profibrotic immune milieu. They also secrete angiogenic factors, including VEGF and angiopoietin-1, promoting sinusoidal remodeling and pathological angiogenesis, which exacerbates portal hypertension in advanced MASH[114].

HSC senescence and MASH

Senescence is defined as a stable state of cell cycle arrest. HSC senescence occurs mainly during fibrosis formation and progression (typically corresponding to fibrosis stages F1-F3)[115,116]. Senescent HSCs lose their proliferative capacity, limiting myofibroblast numbers and indirectly restraining excessive collagen deposition. Furthermore, they secrete SASP[117], including MMPs that degrade ECM to promote fibrosis regression, as well as chemokines recruiting natural killer (NK) cells and KCs to clear senescent HSCs[118]. In advanced liver cirrhosis (stage F4), senescent HSCs decrease, replaced by a cluster of myofibroblasts with higher proliferative activity and anti-senescence properties, which drives irreversible fibrosis[119]. In addition, some senescent HSCs are not efficiently cleared and persist for extended periods. The SASP secreted by these persistent cells undergoes a shift from pro-repair signals to pro-inflammatory, profibrotic, and pro-carcinogenic signals, thereby further exacerbating MASH. In particular, they release large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines, creating a microenvironment of chronic low-grade inflammation that continuously drives liver injury and abnormal tissue repair[120]. This environment inhibits the proliferation and differentiation of hepatic progenitor cells, compromises the liver’s regenerative capacity, disrupts normal tissue structure, and ultimately promotes the development and progression of HCC[121].

Based on the current knowledge of HSCs in MASH, HSC-targeted therapies for MASH primarily focus on inhibiting HSC activation, promoting HSC apoptosis or senescence, and degrading the ECM. Key examples include the apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) inhibitor, selonsertib, which targets stress and fibrosis pathways, but failed in Phase III clinical trials, leading to the cessation of its development[122,123]. The galectin-3 inhibitor belapectin (GR-MD-02) blocks profibrotic lectins, prevents HSC activation, and shows potential in preventing varices in patients without esophageal varices[124]. The lysyl oxidase-like 2 (LOXL2) inhibitor simtuzumab, which inhibits collagen cross-linking, also failed in Phase II trials[125]. The repeated failures of highly selective, single-target drugs have shifted research toward combination therapies. For example, the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist (GLP-1RA) combined with an ACC inhibitor (Semaglutide + Firsocostat) aims to improve the hepatic microenvironment and is currently being evaluated in Phase II trials[126].

The hepatic microenvironment in MASH is a highly interconnected network system in which hepatocytes, LSECs, KCs, and HSCs collectively drive disease progression, from steatosis and inflammation to fibrosis and HCC, through intricate and complex crosstalk. The repeated failure of highly selective single-target drugs underscores the need to develop multi-target drugs or explore combination treatments that modulate the entire liver microenvironment. Achieving this goal requires an in-depth understanding of MASH pathogenesis to identify effective interventions while ensuring drug safety and minimizing complications. Future treatment strategies must move beyond the traditional “single-cell-single-target” approach toward multi-target, combinatorial interventions that holistically improve the microenvironment. Such strategies may include: (i) combination therapies using drugs that target distinct cellular components and pathways (e.g., metabolic modulators + anti-inflammatory agents + anti-fibrotic agents) to achieve synergistic effects; (ii) temporal interventions that provide stage-specific treatments, such as leveraging the beneficial effects of HSC senescence in the early stages of fibrosis while eliminating persistently senescent cells in later stages; and (iii) targeting microenvironmental crosstalk by developing drugs aimed at key signaling nodes (e.g., EVs, specific chemokines, or DAMPs) to simultaneously modulate the pathological behaviors of multiple cell types. A comprehensive understanding of the hepatic microenvironment is therefore the cornerstone for the development of more precise and effective MASH therapies.

CROSSTALK BETWEEN THE LIVER AND OTHER ORGANS IN MASH

As MASH is a chronic metabolic disorder with systemic involvement and multifactorial pathogenesis, a holistic perspective is essential when designing therapeutic strategies[127]. MASH development is not confined to isolated hepatic lesions but reflects an abnormal “axis” communication between the liver and multiple peripheral organs, including the intestine, adipose tissue, and skeletal muscle. This aberrant inter-organ communication synergistically drives disease progression through metabolic disorders, inflammatory activation, and oxidative stress.

Gut-liver axis

The intestine and liver are closely connected via the portal vein, bile acid circulation, and lymphatic system, constituting the “gut-liver axis,” the dysfunction of which is considered a core initiating mechanism of MASH[128]. Using a liver disease progression aggravation diet (LIDPAD), researchers have recapitulated key phenotypic, genetic, and metabolic features of MASLD and identified gut-liver dysregulation as an early event in MASH[129].

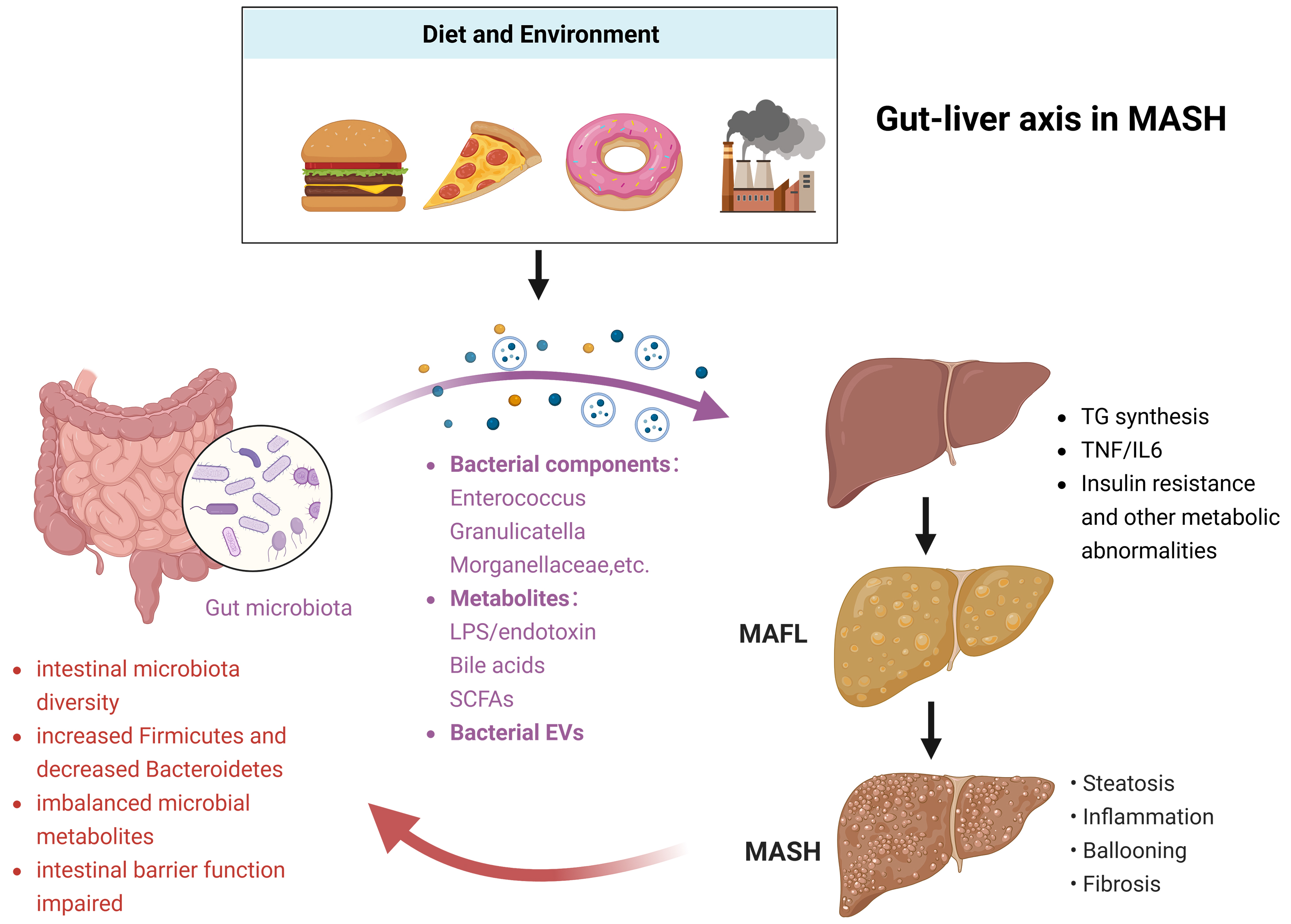

Current evidence indicates that targeting the gut microbiota to regulate bile acid metabolism and other microbial metabolites may ameliorate MASH[130]. Liver-synthesized primary bile acids (e.g., cholic acid) are converted to secondary bile acids (e.g., lithocholic acid) by the intestinal microbiota, which regulate hepatic lipid metabolism through nuclear receptors such as FXR[131]. Microbiota dysbiosis reduces secondary bile acid levels and FXR activity, leading to increased hepatic triglyceride synthesis and steatosis. Selected microbiota-derived metabolites exert protective effects. For example, microbiota-derived 3-succinylcholic acid (3-sucCA) negatively correlates with MAFLD liver injury and alleviates MASH by promoting Akkermansia[132]; the intestinal fungus Fusarium moniliforme ameliorates MASH via the metabolite FF-C1, which inhibits intestinal ceramide synthase 6-ceramide[133]; and Parabacteroides distasonis and its metabolite pentadecanoic acid improve MASH by restoring intestinal barrier integrity and blocking bacterial toxin translocation[134]. Conversely, other metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids, branched-chain amino acids, and trimethylamine-N-oxide can exacerbate liver injury through the gut-liver axis[135]. Additionally, bacterial extracellular vesicles secreted by intestinal microbiota can disrupt the intestinal barrier, enter circulation, and deliver pathogenic factors [e.g., lipopolysaccharide (LPS), bacterial DNA] to the liver. These vesicles induce insulin resistance and activate pathways such as LPS/TLR4, cGAS/STING, and TGF-β to promote MASH progression[136] [Figure 2].

Figure 2. Gut-liver axis in MASH. High-fat diets and environmental factors can induce dysregulation of intestinal flora, bacterial metabolites, and bacterial exosomes. Through the gut-liver axis, these changes promote hepatic lipid overload and inflammatory responses, thereby inducing MASH. As MASH progresses, the liver can further exacerbate intestinal flora dysbiosis and impair the intestinal barrier, which in turn aggravates MASH. Created in BioRender. Fu R (2025) https://app.biorender.com/citation/690b2a930ef7786c9a5418b7. MASH: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; SCFAs: short-chain fatty acids; EVs: extracellular vehicles; MAFL: metabolic-associated fatty liver; MASH: metabolic-associated steatohepatitis; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; IL: interleukin.

Mounting preclinical and clinical evidence has underscored the pivotal role of intestinal barrier integrity in liver injury mediated by the gut-liver axis. The intestinal barrier, composed of a single layer of intestinal epithelial cells, tight junction proteins, and the underlying mucosal immune system, serves as a critical physical and immunological defense line that segregates the luminal contents from the systemic circulation. Disruption of this barrier, termed “intestinal permeability” or “leaky gut”, facilitates the translocation of gut-derived harmful substances - including lipopolysaccharide (LPS), bacterial DNA, and metabolites - into the portal vein, which directly drains into the liver. Among these translocated factors, LPS acts as a key pathogenic molecule by binding to toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), a pattern recognition receptor predominantly expressed on hepatic innate immune cells such as Kupffer cells, hepatic stellate cells, and sinusoidal endothelial cells. This LPS-TLR4 interaction triggers downstream signaling cascades involving myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88) and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), thereby inducing robust pro-inflammatory cytokine production (e.g., tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6) and excessive oxidative stress responses within the liver microenvironment. These pathological processes further promote hepatocellular damage, inflammatory cell infiltration, and extracellular matrix deposition, ultimately initiating or exacerbating the progression of liver injury such as steatohepatitis, fibrosis, and even cirrhosis. Thus, preserving intestinal barrier integrity and targeting the LPS-TLR4 signaling axis have emerged as promising therapeutic strategies for mitigating gut-liver axis-driven liver diseases.

Based on current research, targeting the gut microbiota - by correcting microbiota dysbiosis, modulating the content and variety of its metabolites and other secretions, and regulating gut-liver axis inflammatory signaling - may provide beneficial effects across multiple stages of MASH progression.

Amelioration of microbiota dysbiosis

To improve microbiota dysbiosis, oral administration of beneficial bacteria (probiotics), food components that promote the growth of beneficial bacteria (prebiotics), or metabolites derived from beneficial bacteria (postbiotics) can optimize microbiota composition, reduce LPS translocation into the bloodstream, and alleviate hepatic inflammation. Most of these approaches remain in early clinical or preclinical stages[137]. A major challenge for these strategies lies in the considerable variability in therapeutic stability and individual responsiveness, which complicates large-scale standardization and validation comparable to conventional chemical drugs.

Regulation of gut microbiota metabolites and secretions

Farnesoid X receptor agonists: FXR agonists are one of the most extensively studied potential targets for MASH. By activating FXR, they regulate bile acid synthesis[138]. Current investigational drugs in this class include obeticholic acid (OCA), efruxifermin (AKR-001)[139], TERN-101 (farnesoid X receptor agonist)[140], and EDP-297 (farnesoid X receptor agonist). OCA has been approved for the treatment of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), as it significantly improves cholestasis, liver injury markers, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels, and total/direct bilirubin levels[141]. However, although OCA demonstrated efficacy in improving liver fibrosis in the phase III REGENERATE trial for MASH, its approval for MASH indications in major global markets has been limited due to adverse events such as pruritus and dyslipidemia[142]. The efficacy of other FXR agonists in this class remains under investigation.

Fibroblast growth factor 19 analogues: Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 19 is a hormone produced by intestinal cells following FXR activation. It travels to the liver via the bloodstream, where it exerts negative feedback to inhibit bile acid synthesis and regulate metabolism[143]. Exogenous FGF19 analogs can mimic this physiological process, and the development of such compounds[144] including aldafermin (NGM282) and efruxifermin[145] is underway.

Targeting the gut-liver axis inflammatory signaling: LPS-TLR4 pathway

This strategy focuses on targeting the TLR4 pathway, a key inflammatory signaling axis in gut-liver crosstalk[146]. Examples include intestinal barrier protectants such as aramchol and larazotide, designed to repair damaged intestinal epithelial junctions and reduce LPS leakage, as well as TLR4 inhibitors such as Naronapadenant (JKB-121)[147]. Among these, aramchol[148], a fatty acid-bile acid conjugate and stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1) inhibitor, has advanced most rapidly (NCT04104321, suspended). Trial results showed that MASH patients treated with aramchol (300 mg twice daily) achieved significant improvements in liver fibrosis[149].

Despite the identification of several promising targets, the gut microbiota is a highly individualized ecosystem, making a “one-size-fits-all” therapy challenging. Strategies that directly target the microbiota (e.g., probiotics) or specific microbial products (e.g., LPS) are scientifically compelling, but face significant translational hurdles and remain mostly at early stages of development. Ongoing research efforts continue to focus on identifying MASH-associated key microbiota species, critical metabolites, and corresponding therapeutic targets, as many aspects of this field remain to be explored.

Adipose tissue-liver axis

During MASH, adipose tissue - particularly visceral adipose tissue (VAT) - exhibits “adverse crosstalk” with the liver. Adipocyte-specific ATF3 deletion promotes lipolysis by inducing adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL), which triggers hepatic DNL and inflammatory responses[150]. A clinical study involving 100 patients demonstrated that hepatic lesions in obesity-related MASH are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction in omental VAT. This may disrupt the balance between lipid metabolism and storage, thereby impairing liver function and accelerating pathological adaptive responses[151].

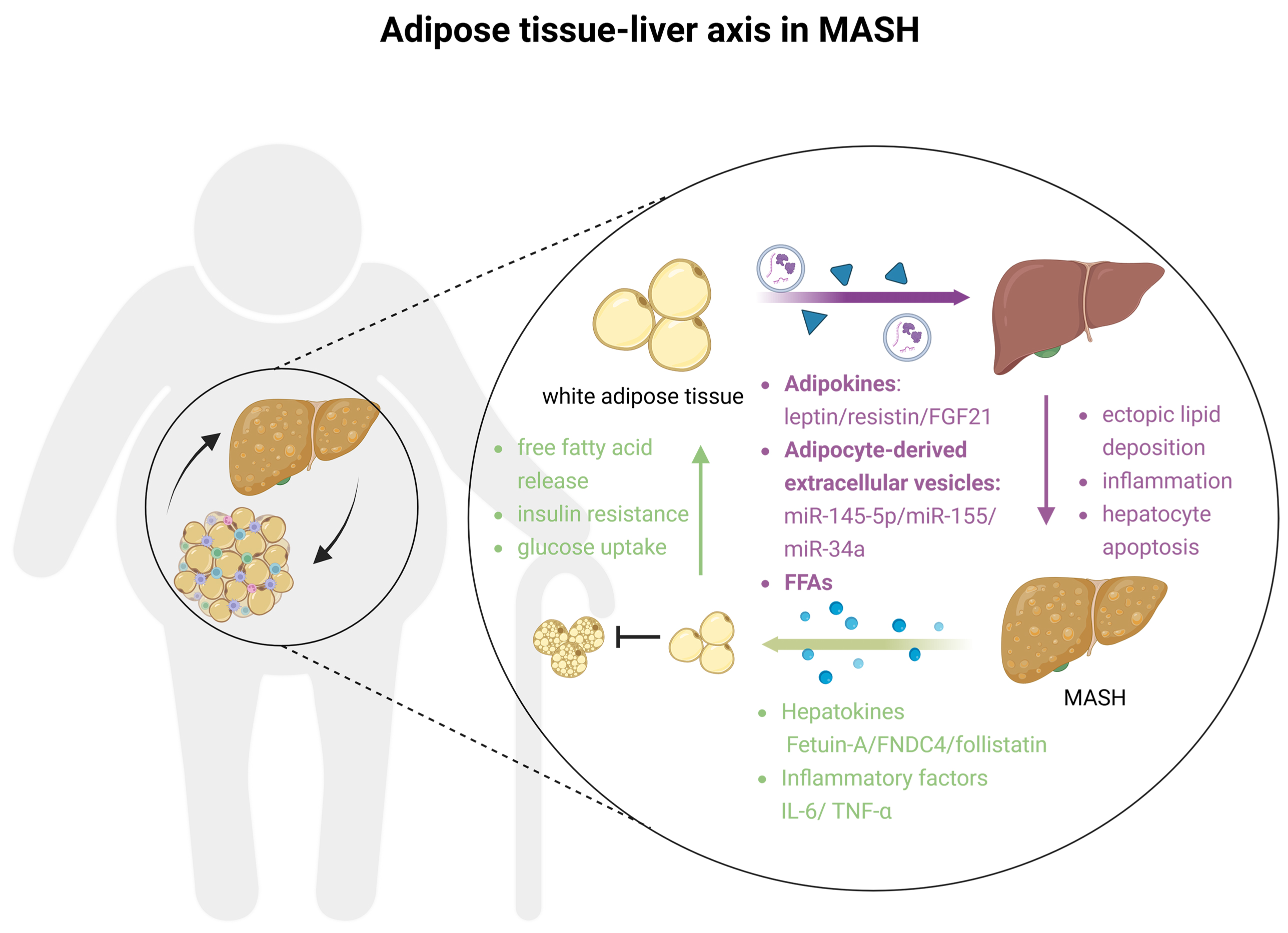

In obesity, excessive expansion of white adipose tissue (WAT) causes adipocyte hypertrophy and mitochondrial dysfunction, shifting WAT to an inflammation-driven state[152,153]. Adipocyte apoptosis and enhanced lipolytic enzyme activity [e.g., hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL)] lead to massive FFA influx into the liver via the portal vein, inducing steatosis and hepatocyte apoptosis. Meanwhile, WAT hypoxia activates hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α), prompting adipocytes to secrete monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), which recruits monocytes that differentiate into M1 macrophages. These macrophages release TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 to activate hepatic TLR4/NF-κB signaling and exacerbate MASH[154]. Additionally, adipokine imbalance occurs; dysfunctional WAT reduces anti-inflammatory, insulin-sensitizing adiponectin while increasing profibrotic leptin and pro-inflammatory resistin, further aggravating MASH[155]. Hepatic inflammatory factors such as IL-6 and TNF-α can, in turn, worsen WAT inflammation and insulin resistance, forming a vicious cycle. In addition, multiple hepatokines also regulate systemic metabolism via the liver-adipose tissue axis[156]. Fetuin-A is the first well-characterized hepatokine. Its hepatic expression is significantly elevated in MASLD patients, and it induces insulin resistance by downregulating the TLR4-mediated inflammatory signaling in adipose tissue[157]. The hepatokine FNDC4 (fibronectin type III domain containing 4) can act on adipose tissue through circulation. Binding to G protein-coupled receptor 116 (GPR116) on the surface of adipocytes promotes insulin signaling and insulin-mediated glucose uptake in white adipocytes, thereby contributing to systemic metabolic homeostasis[158]. Hepatokine follistatin is highly expressed in patients with T2D and is significantly associated with MASH. Studies have shown that follistatin dose-dependently promotes FFA release in human adipocytes, while glucokinase regulatory protein (GCKR) induces adipose tissue insulin resistance by regulating follistatin secretion[159] [Figure 3].

Figure 3. Adipose tissue-liver axis in MASH. In obesity, adipocytes release adipokines, EVs, free fatty acids, and other substances that stimulate ectopic lipid deposition in the liver, trigger inflammatory responses, and induce hepatocyte apoptosis. Hepatic injury, in turn, exacerbates adipocyte hypertrophy, impairs mitochondrial function, and drives a shift from an energy-storing to a pro-inflammatory phenotype in adipose tissue. Furthermore, it inhibits the conversion of adipocytes into brown adipose tissue, further contributing to the development of MASH. Created in BioRender. Fu R (2025) https://BioRender.com/0qyuwby. MASH: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; EVs: extracellular vehicles; FGF21: fibroblast growth factor 21; FFAs: free fatty acids; FNDC4: fibronectin type III domain containing 4; IL: interleukin; TNF: tumor necrosis factor.

Furthermore, intriguingly, MASH also occurs in lean individuals, who present with normal body mass index (BMI) but develop hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and even fibrosis[160]. In these patients, adipose tissue is abnormal, with preferential visceral fat accumulation, subcutaneous adipose dysfunction, severe insulin resistance, and genetic susceptibility (e.g., PNPLA3 mutations)[161]. Lean MASH is often accompanied by gut dysbiosis, which mediates LPS translocation to the liver; VAT is highly sensitive to LPS, exacerbating inflammation and forming a “gut-adipose-liver” vicious cycle that drives hepatic inflammation[162]. The recognition of lean MASH highlights that “qualitative” adipocyte dysfunction is more critical than “quantitative” increase in fat, underscoring the need for individualized MASH therapies.

Current understanding of the adipose tissue-liver axis has led to the identification of multiple therapeutic targets for MASH.

Improving adipose tissue function and insulin sensitivity

Drugs targeting adipose tissue aim to address the root cause of MASH by enhancing adipose health and reducing FFA overflow. PPAR agonists are key agents in this approach. Targeting PPARδ improves systemic insulin sensitivity and fatty acid oxidation, while PPARγ enhances healthy fat storage, adiponectin secretion, and insulin resistance[163]. Representative drugs include: lanifibranor (a pan-PPAR agonist activating α/δ/γ isoforms), which improved inflammation and fibrosis in phase II trials and has progressed to phase III[164]; saroglitazar (a PPARα/γ agonist), approved in India for non-cirrhotic MASH, with phase III ongoing[165]; and elafibranor[166] [a PPARα/δ agonist, (PPARα/δ = peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha/delta)], which showed mixed results in phase II trials but demonstrated benefits in specific patient subgroups.

In addition to PPAR agonists, GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonists have shown promise in improving insulin sensitivity and promoting glucose uptake and utilization. Semaglutide has demonstrated significant efficacy in improving hepatitis in clinical trials of patients with MASH, with a phase III study underway[167]. Similarly, a phase II study of tirzepatide showed significant improvement in histological endpoints in MASH[168].

New strategy: adipocyte-derived extracellular vesicles

Beyond conventional investigational drugs, research on adipocyte-derived extracellular vesicles (Ad-EVs) as a therapeutic avenue for MASH is rapidly advancing. Ad-EVs are key components of the adipose secretome[169]. Adipose tissue “spreads” or “amplifies” its metabolic disorders and inflammatory status to the liver by releasing Ad-EVs, serving as specific material carriers that mediate liver-adipose crosstalk.

Although no drugs directly targeting Ad-EVs have yet entered clinical development, this pathway represents a promising novel therapeutic paradigm[170]. In MASH, detrimental Ad-EVs exacerbate disease progression by delivering select pro-inflammatory and profibrotic miRNAs, proteins, or lipids[171]. In obesity, adipose-derived EVs enriched with fatty acid-binding protein 4 (FABP4) and miR-27a-3p are taken up by hepatocytes, upregulating DNL and downregulating fatty acid oxidation, respectively. These EVs also prime KCs for pro-inflammatory responses, linking systemic metabolic dysfunction to liver injury[172].

Senescent adipose progenitor cells secrete exosomes with reduced levels of miR-145-5p, which upregulates selectin L (SELL) gene expression in adipose tissue macrophages (ATMs), activates the NF-κB pathway, and promotes M1 macrophage polarization, thereby exacerbating insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis[173]. MiR-27b-3p in visceral adipose exosomes targets the protein-coding sequence (CDS) region of hepatic PPARα, inhibiting fatty acid oxidation and promoting the release of inflammatory factors[174]. Due to their inherent biocompatibility, low immunogenicity, and excellent organ tropism especially in the liver, EVs are also promising drug delivery systems. Thus, targeting the generation, release, uptake, or content of EVs could disrupt the “metabolism-immunity-fibrosis” vicious cycle, providing a novel strategy for MASH treatment[175].

Skeletal muscle-liver axis

There is an intrinsic association between MASLD and skeletal muscle metabolic abnormalities. Patients with MASH often exhibit a series of skeletal muscle pathologies such as insulin resistance, myosteatosis, and sarcopenia, which collectively accelerate liver disease progression and worsen patient prognosis through multiple pathways[176]. A clinical study demonstrated that muscle strength closely correlates with key metabolic parameters, including hepatic fat content, LDL levels, and aerobic capacity, which may collectively contribute to the onset and progression of MASH[177].

Skeletal muscle, as the primary site for insulin-mediated glucose uptake, indirectly exacerbates hepatic burden through “metabolic compensation” when its function is impaired[178]. Obesity and physical inactivity reduce insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake in the skeletal muscles. The body compensates by increasing insulin levels (hyperinsulinemia); however, excessive insulin further activates hepatic lipid synthesis pathways [e.g., phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt)/SREBP-1c], promoting fat accumulation[179]. During insulin resistance, impaired translocation of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) to the plasma membrane reduces daily glucose uptake by the skeletal muscle, forcing the liver to increase compensatory gluconeogenesis[180].

Myokines secreted by skeletal muscles (e.g., irisin and titin) play a role in regulating energy metabolism. Alterations in myokine secretion secondary to insulin resistance may negatively impact hepatic metabolic homeostasis and liver histology in MASH[181]. For example, irisin enhances browning of WAT and increases thermogenesis-related energy expenditure, while improving hepatic gluconeogenesis and insulin sensitivity. A decrease in irisin levels lowers systemic energy utilization efficiency and indirectly exacerbates hepatic fat accumulation[182]. Irisin intervention significantly improves sarcopenia indices in aged mice while alleviating age-related adipose tissue expansion, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis[183]. Conversely, the exercise-induced myokine apelin-13 has been reported to upregulate the expression of type I collagen, α-SMA, and cyclin D1 in LX-2 (human hepatic stellate cell line) cells via extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling, thereby inducing hepatic fibrosis in NAFLD models[184]. Myostatin reduces the expression of the hepatic adiponectin receptor AdipoR1 by inhibiting the Smad2/3 signaling pathway, leading to a decrease in adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity and a significant reduction in fatty acid oxidation capacity.

Based on current knowledge of the skeletal muscle-liver axis in MASH, therapeutic strategies can be broadly categorized into two approaches: interventions that directly or indirectly improve skeletal muscle metabolism and function to confer hepatic benefits; and treatments utilizing factors secreted by or acting on skeletal muscle, such as myokines and hormone analogs, to ameliorate MASH.

Directly or indirectly improving skeletal muscle metabolism and function

Studies have identified skeletal muscle as an important source of fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), which enhances insulin signaling and promotes glycogen synthesis[185,186]. In the Phase IIb SYMMETRY trial, treatment with the FGF21 analog Efruxifermin led to significant improvement - 39% of patients with MASH in the 50 mg dose group achieved ≥ 1 stage improvement in liver fibrosis without disease progression[139]. Another FGF21 analog, Pegozafermin[187], is currently being evaluated in the Phase III ENLIGHTEN-Cirrhosis clinical trial for its efficacy in patients with compensated cirrhosis.

Additionally, DR10624 (developed by Doer Biologics), an innovative FGF21R/glucagon receptor (GCGR)/GLP-1R triple agonist, demonstrated remarkable efficacy in a phase 1b/2a study in 2025. After 12 weeks of treatment, the proportions of subjects achieving a relative reduction in liver fat content (LFC) ≥ 50% in the DR10624 dose groups (12.5, 25, 50, and 75 mg) were 66.7%, 88.9%, 100%, and 85.7%, respectively. DR10624 also significantly reduced lipid levels, improved insulin resistance, and was well tolerated with minimal side effects. These findings highlight the efficacy of multi-target agents. By co-activating the FGF21, GCGR, and GLP-1 pathways, DR10624 may exert a synergistic effect on the skeletal muscle-liver axis.

Factors secreted by or acting on skeletal muscle

Currently, most myokine-targeted therapies remain at the preclinical stage. Numerous myokines and muscle metabolism-related secretory proteins have emerged as potential therapeutic targets; however, further research is required to explore their drugability.

The global incidence of MASH continues to rise due to factors such as lifestyle, diet, environmental exposure, and stress. Given the risk of inducing cirrhosis and liver cancer, the urgent need for effective therapies is evident. As a systemic chronic metabolic disorder, MASH may not be adequately addressed by highly selective, single-target agents. Instead, multi-organ therapeutic strategies that simultaneously target metabolic and functional crosstalk between the liver, gut, adipose tissue, and skeletal muscle, which is conceptually aligned with principles of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), may offer improved efficacy and safety [Figure 4]. The only currently approved MASH drug, the THR-β agonist resmetirom, acts through systemic metabolism regulation and achieves 24.2%-29.9% steatohepatitis resolution. However, its therapeutic benefit remains limited, and side effects such as diarrhea highlight ongoing unmet clinical needs[55].

Figure 4. Multitargeted therapy for MASH: a superior approach compared with single-target therapy. In the treatment of MASH, the concept that “multitargeted therapy is superior to single-target therapy” has gradually become a consensus in clinical research and practice. The core reason lies in the complexity of MASH pathogenesis, which involves multiple intertwined links and pathways. Single-target drugs struggle to cover the entire chain of disease progression, whereas multitargeted therapeutic strategies can more effectively modulate the core pathological mechanisms, enhance therapeutic efficacy, and overcome the limitations of single intervention approaches. Created in BioRender. Fu R (2025) https://BioRender.com/qoyo58m. MASH: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis.

Another systemic-regulating agent, aramchol (currently in Phase III), has a clever structure: cholic acid (a primary bile acid) covalently linked to arachidic acid (a saturated fatty acid) via a stable amide bond[188]. This dual-functional design enables aramchol to participate in both bile acid and lipid metabolic pathways, with a long half-life. Mechanistically, aramchol inhibits stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) to reduce pathogenic lipid synthesis, thereby alleviating hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis. In parallel, it modulates the gut microbiota and intestinal barrier, influencing the gut-liver axis. Its derivative, Aramchol Meglumine (structure-optimized), doubles the area under the curve (AUC), enhancing adherence and safety. The FDA has approved its transition from aramchol under an investigational new drug (IND), leveraging prior preclinical and clinical data. Collectively, the development of MASH therapies by regulating systemic homeostasis via liver-multi-organ crosstalk is a promising direction [Table 1].

The roles of single-target drugs, multi-target drugs, and combination regimens in MASH

| Targets | Drugs | Effects | States | NCT number | |

| Failed single-target drugs | Pan-caspase | Emricasan | Reduced serum aminotransferase levels and caspase activation levels in patients with MASH | Failed in Phase II trials | NCT02686762 |

| CCR2/CCR5 | Cenicriviroc | Reduce the infiltration of inflammatory cells in the liver, thereby alleviating inflammation and indirectly exerting anti-fibrotic effects | Failed in Phase III trials | NCT03028740 | |

| ASK1 | Selonsertib | Stimulated insulin secretion, inhibited glucagon release, thereby reducing blood glucose levels, and suppresses inflammatory responses as well as the progression of hepatic fibrosis | Failed in Phase III trials | NCT03053050 | |

| LOXL2 | Simtuzumab | Inhibited collagen cross-linking | Failed in Phase IIb trials | NCT01672866 and NCT01672879 | |

| FXR ligand | Obeticholic acid | Inhibited bile acid synthesis and had demonstrated efficacy in improving liver fibrosis | Failed in Phase III trials | NCT02548351 | |

| PPARα/δ | Elafibranor | Efficacy on insulin resistance and serum lipid normalization | Failed in Phase III trials | NCT02704403 | |

| Ongoing multi-target drugs | Fatty acid-bile acid conjugate and stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 inhibitor | Aramchol | Patients with MASH treated with aramchol (300 mg twice daily) achieved significant improvements in liver fibrosis | Phase III trials | NCT04104321 |

| Fatty acid-bile acid conjugate and stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 inhibitor | Aramchol Meglumine(structure-optimized) | Optimization based on the structure of Aramchol significantly improves its bioavailability | Currently in Phase I: comparing the PK of Aramchol Meglumine Granules to Aramchol Free Acid Tablets | NCT06502561 | |

| FGF21R/GCGR/GLP-1R triple | DR10624 | Currently the fastest-advancing FGF21-based triple-target drug with a unique target combination, comprehensively regulating blood glucose, body weight, and blood lipids | Currently in Phase II trials | NCT07024212 | |

| FGF21/GIPR/GLP-1R triple | GGG (LM-001) | Designed to integrate the potent weight loss effect of GLP-1, the metabolic enhancement of GIP, and the direct hepatoprotective and anti-fibrotic effects of FGF21 | IND | IND | |

| FGF21+ GLP-1R | AP026 | A recombinant polypeptide designed to improve MASH by enhancing metabolism and protecting the liver | Currently in Phase I trials | NCT06143423 | |

| GCGR/GLP-1R | Survodutide | The GLP-1R moiety is responsible for weight loss and glycemic control, while the GCGR moiety directly promotes hepatic lipolysis and energy expenditure, conferring direct benefits to the liver | Currently in Phase III trials | NCT06632444 | |

| Ongoing combination therapy | ACC1/2 + FXR | Firsocostat + Cilofexor | In patients with bridging fibrosis and cirrhosis due to MASH, combination therapy effectively reduces the NAS score | Finished Phase II trials | NCT03449446 |

| GLP-1R + ACC1/2 /FXR | Semaglutide + Firsocostat/Cilofexor | In patients with mild-to-moderate liver fibrosis due to NASH, combination therapy further improves hepatic steatosis and biochemical markers with good tolerance | Finished Phase II trials | NCT03987074 | |

| GLP-1R + FGF21 | Semaglutide + Efruxifermin | For patients already receiving GLP-1RA therapy, the addition of Efruxifermin could further significantly improve liver health | Currently in Phase II trials | NCT05039450 | |

| ACC1/2 + DGAT2 | PF-05221304 + PF-06865571 | Combination could reduce fat accumulation and mitigate the effect of ACC inhibitors on serum triglycerides | Finished Phase II trials | NCT03776175 |

CONCLUSION

This review systematically discusses the pathogenesis of MASH, emphasizing that it is not merely a liver-autonomous disease but a systemic metabolic disorder driven by hepatic microenvironment dysregulation and abnormal inter-organ crosstalk. This understanding provides crucial insights for guiding future drug development.

First, the complexity of the hepatic microenvironment explains the repeated failure of numerous highly selective single-target drugs in clinical trials. Hepatocytes, LSECs, KCs, and HSCs form an elaborate network via cell-cell contact, soluble mediators, and extracellular vesicles. Inhibiting a single node within this network is often insufficient, as compensatory mechanisms within other components of the network can neutralize therapeutic effects, leading to therapeutic failure. For example, CVC can block monocyte infiltration but fails to address hepatocellular lipotoxicity, a persistent source of inflammation, while selonsertib inhibits the ASK1 stress pathway but hardly reverses advanced fibrosis maintained by multiple signaling pathways. Therefore, future research should focus on multi-target drugs or rationally designed drug combination therapies aimed at improving multicellular crosstalk to simultaneously break the vicious cycle of metabolic abnormalities, inflammation, and fibrosis.

Second, the crosstalk between the liver and peripheral organs provides a broader, systemic perspective for MASH treatment. The discovery of the gut-liver, adipose-liver, and muscle-liver axes demonstrates that the liver acts as both a “victim” and an “amplifier” of systemic metabolic disorders. Consequently, the most effective treatment may not act directly on the liver but may indirectly improve liver health by regulating these inter-organ axes. The mechanisms of drugs such as FXR agonists, FGF21 analogs, and GLP-1RAs reflect this idea, as they restore systemic metabolic homeostasis by simulating or enhancing beneficial inter-organ signals (e.g., the FXR-FGF15/19 axis). The recently approved THRβ agonist, resmetirom, and the promising agent, aramchol, are systemic metabolic modulators. The development of drugs that regulate liver-multi-organ crosstalk is a highly promising direction, which may yield higher efficacy and better safety.

Based on the above discussion, we propose two core strategies for future MASH drug development.

1. Multi-target combination strategy: Given the complexity of the disease, future therapeutic therapies will inevitably rely on combination therapies. An ideal combination should integrate a metabolic modulator (e.g., resmetirom, GLP-1RA, or FGF21 analog) with an anti-inflammatory or anti-fibrotic agent (e.g., drugs targeting specific macrophage subsets or HSC activation) to simultaneously address both upstream etiologies and downstream tissue damage.

2. Precision medicine strategy: MASH patients exhibit high heterogeneity (e.g., obese vs. lean MASH). Future clinical trials and practices should stratify patients according to their genetic background (e.g., PNPLA3 and HSD17B13 variants), dominant pathological phenotypes (inflammation- or fibrosis-dominant), and characteristics of inter-organ axis disorders (e.g., gut microbiota composition, fat distribution), thereby achieving truly individualized therapies.

Combination therapies based on multi-target intervention and cross-organ crosstalk modulation have emerged as promising strategies for MASH, given the disease’s complex, multifactorial pathogenesis involving metabolic dysregulation, hepatic inflammation, and fibrogenesis. However, these innovative approaches are not without limitations. Notably, the co-targeting of distinct signaling pathways or organ interfaces may trigger unexpected target-related antagonism or off-target effects: for instance, concurrent modulation of lipid metabolism and inflammatory cascades could disrupt systemic metabolic homeostasis, leading to adverse events such as dyslipidemia or immunosuppression. Additionally, the intricate interplay between different organs poses challenges in optimizing drug dosages and administration timelines, as interventions targeting one organ (e.g., the gut) may inadvertently perturb physiological functions in another (e.g., the liver or adipose tissue), thereby compromising treatment efficacy and safety.

In conclusion, overcoming MASH requires a paradigm shift from the traditional linear model of “single target, single organ” toward a systemic approach of “multi-target, multi-organ” intervention. By gaining in-depth insights into the dynamic networks of the hepatic microenvironment and systems biology, the development of innovative multi-target drugs and combination strategies holds the promise of effective solutions to this increasingly critical global health challenge.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgements

All figures included in this review were created using Biorender (https://biorender.com/). The Graphical Abstract was also created in BioRender [Fu R (2025) https://app.biorender.com/citation/690b2b152cfe0adad44b496f].

Authors’ contributions

Wrote the initial draft and revised the manuscript: Fu R

Conducted the literature search and assisted in drafting the manuscript: Zhang F

Reviewed the manuscript for scientific accuracy and suggested revisions: Fu J, Li Y

Contributed to the discussion on future research directions: Zhu X

Supervised the overall project and finalized the manuscript: Zhu YZ, Ding Q

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Macau Science and Technology Development Fund (FDCT: 0012/2021/AMJ,0001/2024/RDP,0001/2024/AKP,0092/2022/A2,0144/2022/A3), the Shenzhen-Hong Kong-Macao Science and Technology Fund (Category C: SGDX20220530111203020), and Amway (China) Fund (Grant/Award Numbers: Am20230494RD and Am20230602RD). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. They also confirm that this manuscript, including all Figures and Table, is their original work, which has not been previously published and is not under consideration for publication by any other journal.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:11-20.

3. Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3,663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2024;403:1027-50.

5. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73-84.

6. Mitra S, De A, Chowdhury A. Epidemiology of non-alcoholic and alcoholic fatty liver diseases. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:16.

7. Estes C, Anstee QM, Arias-Loste MT, et al. Modeling NAFLD disease burden in China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States for the period 2016-2030. J Hepatol. 2018;69:896-904.

8. Asrani SK, Devarbhavi H, Eaton J, Kamath PS. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol. 2019;70:151-71.

9. Charlton MR, Burns JM, Pedersen RA, Watt KD, Heimbach JK, Dierkhising RA. Frequency and outcomes of liver transplantation for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1249-53.

10. Estes C, Razavi H, Loomba R, Younossi Z, Sanyal AJ. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology. 2018;67:123-33.

11. Younossi Z, Tacke F, Arrese M, et al. Global perspectives on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2019;69:2672-82.

12. Targher G, Byrne CD, Tilg H. MASLD: a systemic metabolic disorder with cardiovascular and malignant complications. Gut. 2024;73:691-702.

13. Huang DQ, Wong VWS, Rinella ME, et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in adults. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2025;11:14.

14. Mittal S, El-Serag HB, Sada YH, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of cirrhosis in United States veterans is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:124-31.e1.

15. Hardy T, Oakley F, Anstee QM, Day CP. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: pathogenesis and disease spectrum. Annu Rev Pathol. 2016;11:451-96.

16. Bertot LC, Adams LA. Trends in hepatocellular carcinoma due to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;13:179-87.

17. Tilg H, Moschen AR. Evolution of inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the multiple parallel hits hypothesis. Hepatology. 2010;52:1836-46.

18. Connor CL. Fatty infiltration of the liver and the development of cirrhosis in diabetes and chronic alcoholism. Am J Pathol. 1938;14:347-64.9.

19. Chen Z, Tian R, She Z, Cai J, Li H. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;152:116-41.

20. Schwärzler J, Grabherr F, Grander C, Adolph TE, Tilg H. The pathophysiology of MASLD: an immunometabolic perspective. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2024;20:375-86.

21. Friedman SL, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Rinella M, Sanyal AJ. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med. 2018;24:908-22.

22. Stefan N, Targher G. Clusters of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease for precision medicine. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;22:226-7.

23. Luukkonen PK, Porthan K, Ahlholm N, et al. The PNPLA3 I148M variant increases ketogenesis and decreases hepatic de novo lipogenesis and mitochondrial function in humans. Cell Metab. 2023;35:1887-1896.e5.

24. Liu DJ, Peloso GM, Yu H, et al.; Charge Diabetes Working Group. Exome-wide association study of plasma lipids in > 300,000 individuals. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1758-66.

25. Wu Q, Yang Y, Lin S, Geller DA, Yan Y. The microenvironment in the development of MASLD-MASH-HCC and associated therapeutic in MASH-HCC. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1569915.

27. Povero D, Yamashita H, Ren W, et al. Characterization and proteome of circulating extracellular vesicles as potential biomarkers for NASH. Hepatol Commun. 2020;4:1263-78.

28. Newman LA, Useckaite Z, Johnson J, Sorich MJ, Hopkins AM, Rowland A. Selective isolation of liver-derived extracellular vesicles redefines performance of miRNA biomarkers for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Biomedicines. 2022;10:195.

29. Xu Y, Zhu Y, Hu S, et al. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α prevents the steatosis-to-NASH progression by regulating p53 and bile acid signaling (in mice). Hepatology. 2021;73:2251-65.

30. Lan T, Hu Y, Hu F, et al. Hepatocyte glutathione S-transferase mu 2 prevents non-alcoholic steatohepatitis by suppressing ASK1 signaling. J Hepatol. 2022;76:407-19.

31. An P, Wei LL, Zhao S, et al. Hepatocyte mitochondria-derived danger signals directly activate hepatic stellate cells and drive progression of liver fibrosis. Nat Commun. 2020;11:2362.

32. Xiao Y, Batmanov K, Hu W, et al. Hepatocytes demarcated by EphB2 contribute to the progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Sci Transl Med. 2023;15:eadc9653.

33. Xu F, Guo M, Huang W, et al. Annexin A5 regulates hepatic macrophage polarization via directly targeting PKM2 and ameliorates NASH. Redox Biol. 2020;36:101634.

34. Liu XL, Pan Q, Cao HX, et al. Lipotoxic hepatocyte-derived exosomal microRNA 192-5p activates macrophages through Rictor/Akt/Forkhead box transcription factor O1 signaling in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2020;72:454-69.

35. Liao CY, Song MJ, Gao Y, Mauer AS, Revzin A, Malhi H. Hepatocyte-derived lipotoxic extracellular vesicle sphingosine 1-phosphate induces macrophage chemotaxis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2980.

36. Guo Q, Furuta K, Lucien F, et al. Integrin β1-enriched extracellular vesicles mediate monocyte adhesion and promote liver inflammation in murine NASH. J Hepatol. 2019;71:1193-205.

37. Dasgupta D, Nakao Y, Mauer AS, et al. IRE1A stimulates hepatocyte-derived extracellular vesicles that promote inflammation in mice with steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1487-1503.e17.

38. Hirsova P, Ibrahim SH, Krishnan A, et al. Lipid-induced signaling causes release of inflammatory extracellular vesicles from hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:956-67.

39. Kumar S, Duan Q, Wu R, Harris EN, Su Q. Pathophysiological communication between hepatocytes and non-parenchymal cells in liver injury from NAFLD to liver fibrosis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;176:113869.

40. Ma F, Liu Y, Hu Z, et al. Intrahepatic osteopontin signaling by CREBZF defines a checkpoint for steatosis-to-NASH progression. Hepatology. 2023;78:1492-505.

41. Chiabotto G, Ceccotti E, Tapparo M, Camussi G, Bruno S. Human liver stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles target hepatic stellate cells and attenuate their pro-fibrotic phenotype. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:777462.

42. Koenen MT, Brandt EF, Kaczor DM, et al. Extracellular vesicles from steatotic hepatocytes provoke pro-fibrotic responses in cultured stellate cells. Biomolecules. 2022;12:698.

43. Bruno S, Pasquino C, Herrera Sanchez MB, et al. HLSC-derived extracellular vesicles attenuate liver fibrosis and inflammation in a murine model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Mol Ther. 2020;28:479-89.

44. Povero D, Panera N, Eguchi A, et al. Lipid-induced hepatocyte-derived extracellular vesicles regulate hepatic stellate cell via microRNAs targeting PPAR-γ. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;1:646-663.e4.

45. Liu X, Tan S, Liu H, et al. Hepatocyte-derived MASP1-enriched small extracellular vesicles activate HSCs to promote liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2023;77:1181-97.

46. Baboota RK, Rawshani A, Bonnet L, et al. BMP4 and Gremlin 1 regulate hepatic cell senescence during clinical progression of NAFLD/NASH. Nat Metab. 2022;4:1007-21.

47. Du K, Umbaugh DS, Wang L, et al. Targeting senescent hepatocytes for treatment of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and multi-organ dysfunction. Nat Commun. 2025;16:3038.

48. Park J, Chen Y, Kim J, et al. CO-induced TTP activation alleviates cellular senescence and age-dependent hepatic steatosis via downregulation of PAI-1. Aging Dis. 2023;14:484-501.

49. Antwi MB, Lefere S, Clarisse D, et al. PPARα-ERRα crosstalk mitigates metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease progression. Metabolism. 2025;164:156128.

50. Cooreman MP, Vonghia L, Francque SM. MASLD/MASH and type 2 diabetes: two sides of the same coin? Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2024;212:111688.

51. Calle RA, Amin NB, Carvajal-Gonzalez S, et al. ACC inhibitor alone or co-administered with a DGAT2 inhibitor in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: two parallel, placebo-controlled, randomized phase 2a trials. Nat Med. 2021;27:1836-48.

52. Chen L, Duan Y, Wei H, et al. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) as a therapeutic target for metabolic syndrome and recent developments in ACC1/2 inhibitors. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2019;28:917-30.

53. Alkhouri N, Lawitz E, Noureddin M, DeFronzo R, Shulman GI. GS-0976 (Firsocostat): an investigational liver-directed acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) inhibitor for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2020;29:135-41.

54. Loomba R, Noureddin M, Kowdley KV, et al.; for the ATLAS Investigators. Combination therapies including cilofexor and firsocostat for bridging fibrosis and cirrhosis attributable to NASH. Hepatology. 2021;73:625-43.

55. Harrison SA, Bedossa P, Guy CD, et al.; MAESTRO-NASH Investigators. A phase 3, randomized, controlled trial of resmetirom in NASH with liver fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:497-509.