Design and application of metal-organic framework-derived catalysts for oxygen reduction in energy conversion devices

Abstract

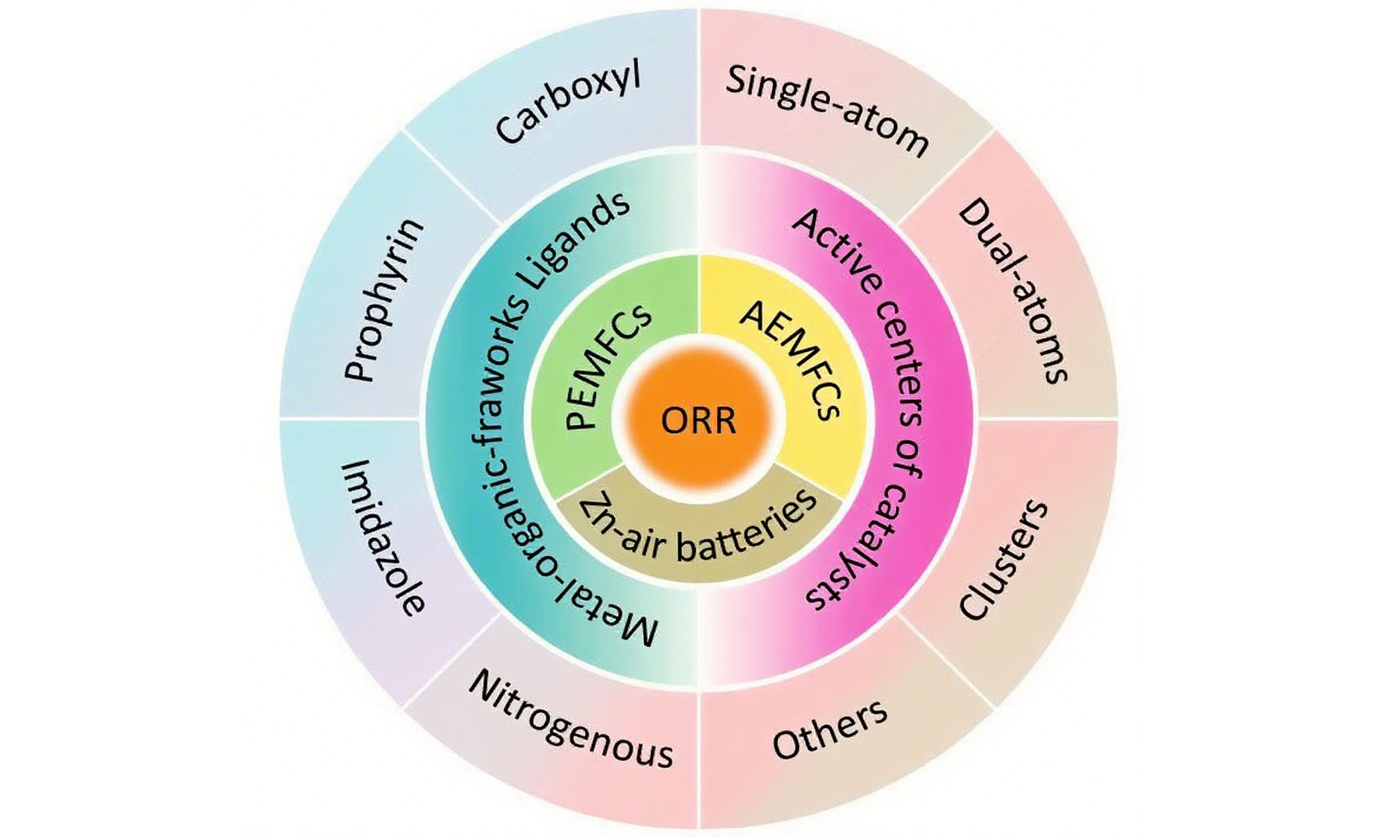

The oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) is a clean energy conversion process with the potential to address the current energy crisis and promote the adoption of clean energy sources. Developing high-activity catalysts is essential to accelerate the inherently slow ORR kinetics and improve overall efficiency. Atomic-level oxygen reduction catalysts can be prepared through pyrolysis and solvothermal synthesis, using metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) as precursors or templates. This approach preserves the structural advantages of MOFs while enabling precise, atomic-scale tuning of catalyst composition and structure, thereby optimizing their ORR catalytic performance. Advances in catalyst synthesis and characterization methods have improved the understanding of the dynamic evolution of active centers and ORR performance in real-world devices. This paper provides a comprehensive review of ORR mechanisms, describes MOF-derived ORR catalytic materials with distinct ligands, and classifies them by ligand type to elaborate on the role of ligands in catalyst derivation and their influence on ORR performance. It further discusses the tuning of various MOF-derived catalyst types-single-atom, dual-atom, and cluster configurations-through precise control of metal content and species, exploring the relationship between catalyst architecture and ORR activity. The challenges of real-time monitoring of MOF pyrolysis and of understanding dynamic metal coordination during catalytic processes are also discussed. Finally, it examines the future prospects and challenges of MOF-based catalysts for the ORR.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Continuous economic progress has increasingly intensified the conflict between energy and environmental protection[1-3]. Advanced clean energy conversion devices, such as fuel cells and Zn-air batteries (ZABs), are considered promising solutions to this challenge[4-8]. However, the cathodic oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) on which these devices rely suffers from slow kinetics, necessitating the use of expensive

MOFs are porous coordination polymers constructed from organic ligands and metal ions or clusters[25]. Since the first MOF was reported in 1995, nearly three decades of research have produced tens of thousands of MOF structures, with novel frameworks continually emerging. In recent years, their exceptional properties and broad potential have been leveraged in various applications, including adsorption, separation, catalysis, sensing, and ionic conductivity. In catalysis, MOFs stand out for their unique advantages, including diverse metal centers, flexible structural design, and tunable organic ligands[26-30]. These characteristics have drawn notable attention from scientists across multiple disciplines, reflecting a clear trend toward interdisciplinary research[31-37]. Moreover, by tailoring pore types and sizes and modifying structural models, researchers have created a wide range of potential MOF configurations[38-40]. MOFs have recently been employed as templates for synthesizing metal-nitrogen-carbon (M-N-C) catalysts and extensively studied for ORR applications[41-45]. The individual components of MOFs play distinct roles during material derivation, enabling the creation of diverse new materials[46-49]. For instance, some MOFs form stable single-atom materials after calcination, whereas others yield nanoparticles (NPs)[50]. This morphological diversity is closely linked to the ligands and metal species in MOFs.

It is well known that most MOFs are nonconductive and require a treatment process to become ORR catalysts, involving changes to their ligands and metal coordination environment. However, no systematic summary exists on which MOFs ligands can be post-treated to obtain ORR catalysts, why some MOFs thermally decompose to form single-atom sites, dual-atom sites, nanoclusters and so on, and how these transformations influence ORR performance. This review aims to bridge the gap between MOF materials and ORR catalysts by summarizing recent applications of MOF-based catalysts for ORR from the perspectives of ligands and metals.

Advancing the applications of MOF-based materials requires a thorough understanding of the interplay between MOFs and their derivatives, as well as the correlation between the original MOF architecture and the properties of MOF-derived materials. To examine this relationship, this review first analyzes MOF ligands and metal/metal clusters, then summarizes recent progress on how MOF structures and their derivatives influence ORR and energy conversion devices. The discussion begins with MOF-derived ORR catalytic materials categorized by ligand type, detailing their role in catalyst derivation and their influence on ORR performance. It then shifts to the modulation of MOF-derived catalyst architectures-single-atom, dual-atom, and cluster configurations-through precise control of metal content and species, followed by an exploration of the relationship between catalyst structure and ORR activity. For example, ligand design governs the formation of hierarchical pores, metal dispersion, and active-site configurations during pyrolysis; morphological tuning improves mass transport; and adjustments to the chemical environment can modulate electronic properties to enhance ORR kinetics. Building on these insights, the review presents a comprehensive summary of coordination-control strategies for MOF-based catalysts in ORR, highlighting how precise manipulation of metal-ligand interactions can stabilize single-atom sites and optimize their geometric and electronic structures for efficient oxygen activation. The article concludes with a discussion of future opportunities and challenges for MOF-based ORR catalysts.

FUNDAMENTALS OF THE OXYGEN REDUCTION REACTION

Mechanism of the oxygen reduction reaction

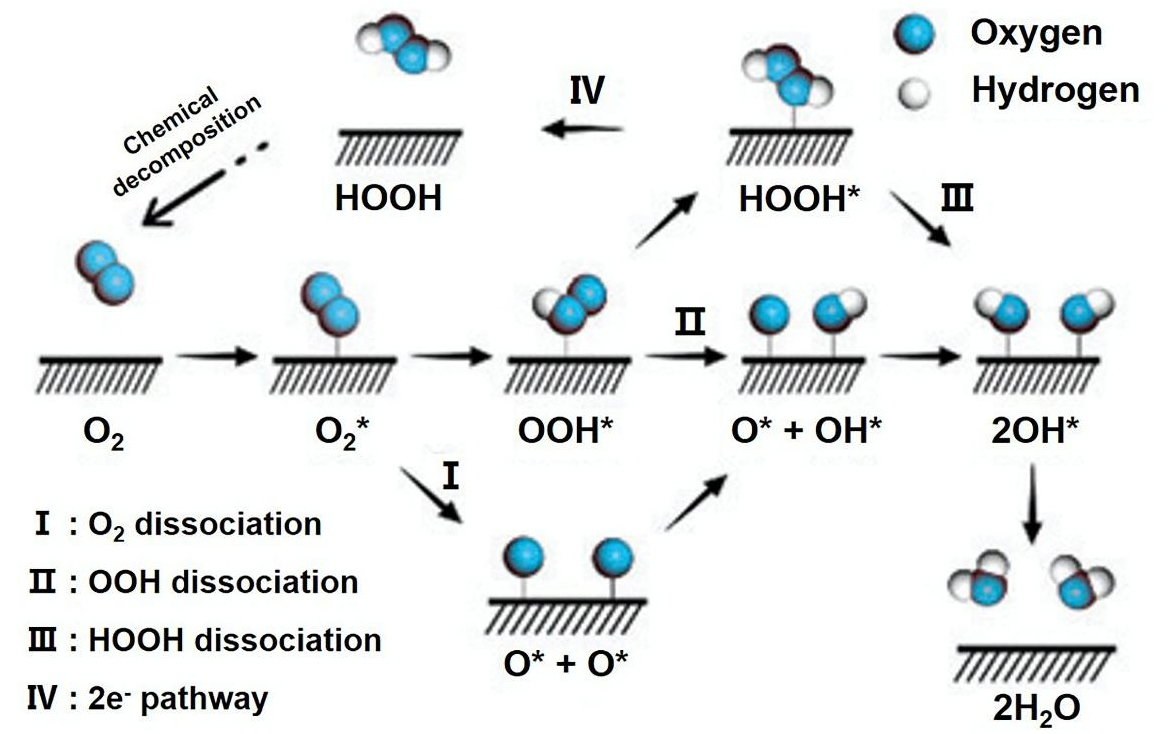

The electrocatalytic oxygen reduction process comprises two competing reactions: the 2e- conversion process and the 4e- conversion process[51,52], which convert O2 into H2O2 and O2 into H2O, respectively[53] [Figure 1]. As the 2e- transfer exhibits much lower energy conversion efficiency than the 4e- transfer, the latter predominates in energy conversion devices[54].

Figure 1. Molecular model of the oxygen reduction reaction process (reproduced with permission from Royal Society of Chemistry, copyright 2021)[53].

In the first stage of the ORR process, freely diffusing O2 adsorbs onto the catalyst surface, forming adsorbed O2*. Further reduction occurs via one of three main pathways: the dissociation pathway, the coalescence pathway, or the peroxide (secondary coalescence) pathway. In the dissociation pathway, the O-O bond is broken prior to electron and proton adsorption, forming two O* adsorption intermediates that are subsequently reduced to OH* and then to hydroxide anion (OH-) (steps 1 and 2). In the coalescence pathway, electrons and protons combine to form OOH* before O-O bond rupture; cleavage of the O-O bond in OOH* yields O* and OH* intermediates, which are further hydrogenated to form OH- (steps 3-6). The peroxide pathway is a branch of the associative pathway, in which O2 binds to the catalyst surface before O-O bond cleavage. The OOH* intermediate is reduced to hydrogen peroxide at the active site

Dissociation pathway:

Coalescence pathway:

Peroxy pathway:

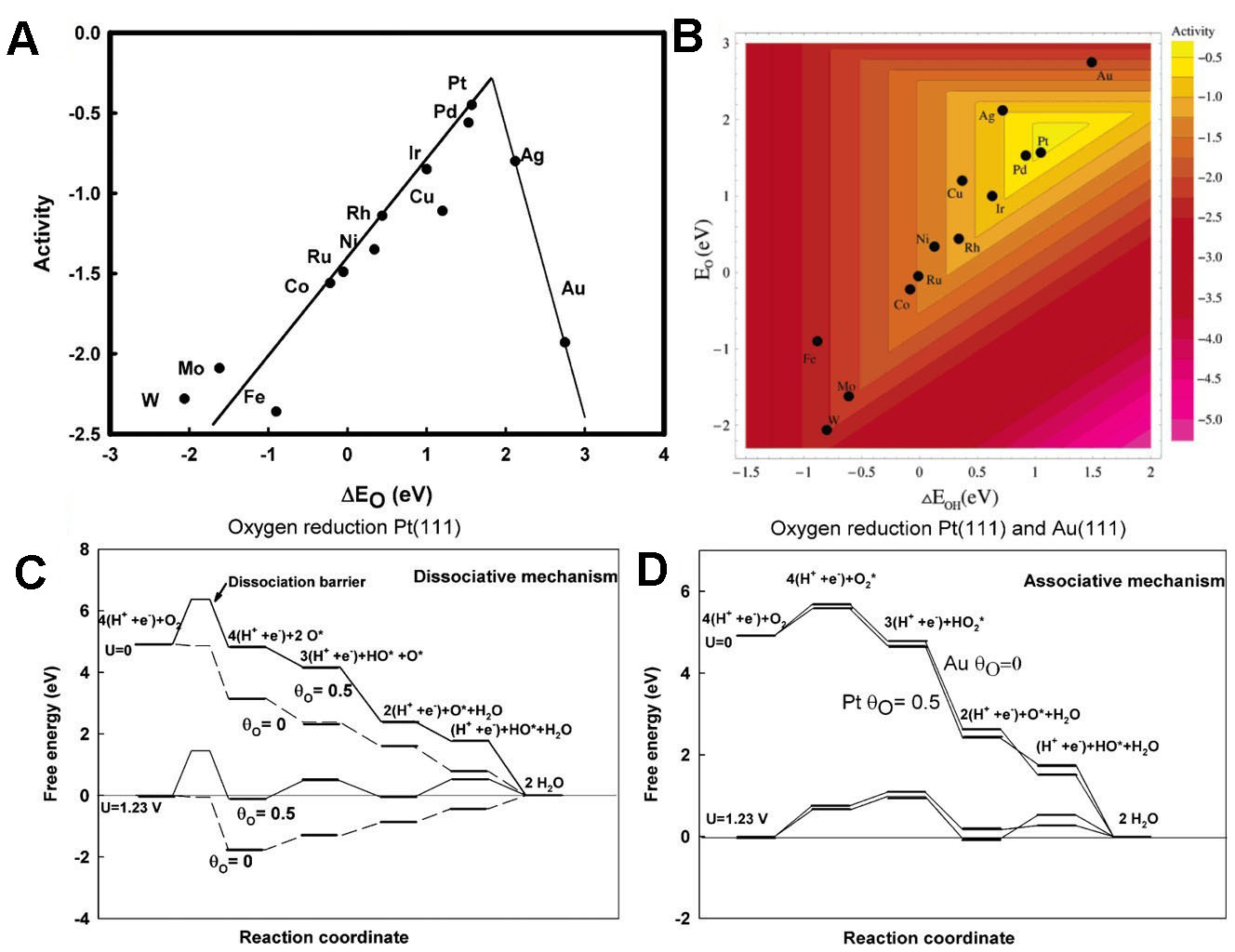

Figure 2A presents a volcano plot of the O-binding energy functions of different metals, and Figure 2B shows a volcano plot of the binding energy functions of O and OH. Clearly, Pt and Pd are the most effective metals for oxygen reduction catalysis. As demonstrated in Figure 2C, the mechanism underlying the calculated changes in oxygen reduction free energy and oxygen dissociation potential barrier is illustrated. The process and dissociation reaction schemes are identical [Figure 2D]. The binding mechanisms of

Figure 2. Function diagrams of (A) O binding energies and (B) O-OH binding energies for different metals; Free energy diagrams of (C) oxygen reduction under different potentials and oxygen coverages, including the oxygen dissociation potential barrier, and (D) the oxygen peroxidation mechanism under low oxygen coverage of Au (111) and 1/2 oxygen coverage of Pt (111). A-D reproduced with permission from the American Chemical Society, copyright 2004[56].

Development of devices for the ORR

Traditional extraction of fossil fuels, including oil and coal, is depleting natural resources and degrading the environment. To address these issues, governments and businesses worldwide are investing in the advancement and integration of new energy sources[57-59], accelerating the transition from traditional energy sources to clean and efficient alternatives. Hydrogen energy, in particular, has attracted increasing attention from the scientific community as a promising new energy source[60-65], driving considerable research into hydrogen energy conversion devices such as proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs) and

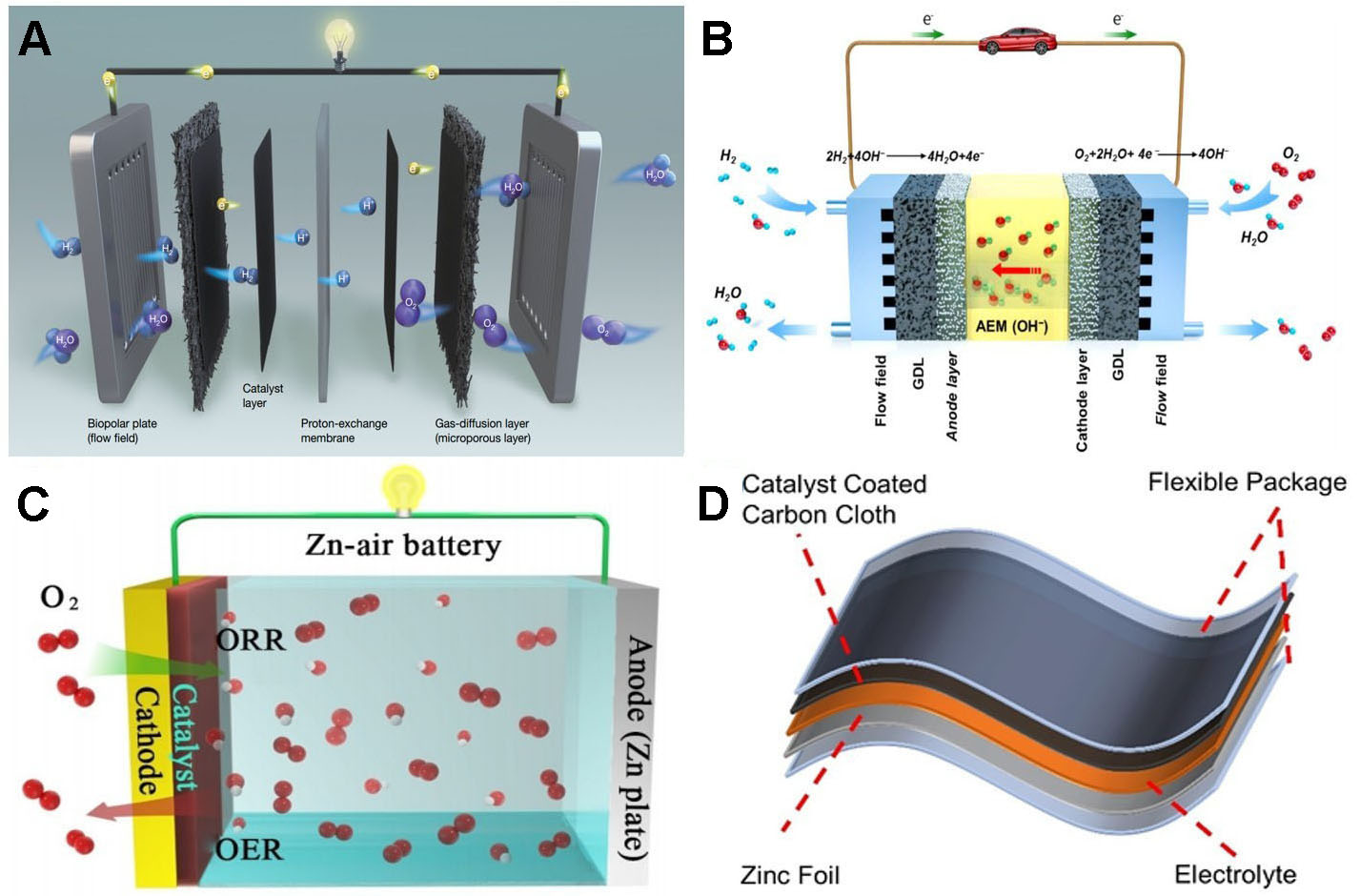

Proton-exchange membrane fuel cells

PEMFCs are considered a potentially viable power source for electric vehicles[71,72]. A PEMFC comprises four primary components: a bipolar plate, a catalyst layer, a proton-exchange membrane, and a gas-diffusion layer [Figure 3A][73]. Of these, the catalyst layer plays the most critical role in determining maximum power density, while the other components are largely supportive. Significant improvements in catalyst activity and catalyst-layer design remain necessary[74]. Commercial Pt/C catalysts, though widely used, are costly and insufficiently stable[75], creating demand for efficient catalysts containing low Pt content or entirely without platinum group metals[76]. Numerous M-N-C catalysts have exhibited performance comparable to Pt/C in rotating disk electrode (RDE) tests[77]. However, the acidic operating environment in which PEMFCs operate diminishes catalyst effectiveness in membrane electrode evaluations and hinders industrial application. The replacement of precious metal catalysts remains a major challenge.

Anion-exchange membrane fuel cells

In AEMFCs, the proton exchange membrane of PEMFCs is replaced with an anion-exchange membrane [Figure 3B], thereby creating an alkaline working environment that reduces the leaching of transition metals[78]. This significantly enhances the practicality of M-N-C catalysts and substantially lowers costs[79]. However, AEMFCs require more expensive auxiliary components than PEMFCs. Even so, AEMFC catalysts are expected to offer enhanced performance at lower overall cost. The coordination structure of M-N-C catalysts is difficult to control, making it challenging to balance metal site density and reaction mass transfer resistance-an imbalance that largely influences catalytic performance[80]. Furthermore, AEMFC efficiency and stability are marginally inferior to those of PEMFCs[78]. Developing catalysts with stable coordination structures that optimize catalytic performance and stability remains a top priority.

Figure 3. (A) Diagrams of the structure and working principle of proton-exchange membrane fuel cells (reproduced with permission from Springer Nature, copyright 2021)[73]; Schematics of (B) an anion-exchange membrane fuel cell (reproduced with permission from Elsevier, copyright 2021)[78], (C) a liquid Zn-air battery (reproduced with permission from Wiley-VCH, copyright 2023)[88], and (D) a solid flexible Zn-air battery (reproduced with permission from Wiley-VCH, copyright 2023)[90]. ORR: Oxygen reduction reaction; OER: oxygen evolution reaction; AEM: anion-exchange membrane.

Zn-air batteries

Metal-air batteries are clean energy storage devices that convert chemical energy into electrical energy through the oxidation reaction of metals inside the battery[81,82]. Among them, ZABs are the most widely studied, offering high energy density, low production cost, and safe operation [Figure 3C][83,84]. They are suitable for extensive applications across diverse domains, such as large-scale energy storage, new energy vehicles, and portable devices[85-87]. In ZABs, Zn plates serve as the anode and air as the cathode-an arrangement that is cost-effective, nontoxic, and environmentally friendly[88]. Nevertheless, the conventional liquid electrolytes used in ZABs are inconvenient[89], prompting the development of flexible ZABs with solid electrolytes

The requirements for ORR catalysts vary among energy conversion devices. PEMFCs, the only devices operating in an acidic environment, demand catalysts with high activity and stability under acidic conditions. AEMFCs and traditional ZABs require catalysts optimized for alkaline conditions. Flexible ZABs, as a distinct class, require catalysts with dual functionality for both the ORR and oxygen evolution reaction, which is essential for their unique charge-discharge cycles.

MOFS WITH DIFFERENT LIGAND-DERIVED CATALYSTS

The ligands in MOFs play a crucial role in constructing MOF topology and regulating crystal morphology. In addition to providing structural support, they determine pore dimensions and geometries, and enable the incorporation of functional moieties or chiral centers for post-modification-attributes of paramount importance in ORR catalyst derivation[92]. Through the rational design of ligands and coordination modes, the performance characteristics of MOF-derived catalysts can be systematically modulated, facilitating the transition from fundamental research to practical applications[93]. The most prevalent MOFs include the Materials Research Institute Lavoisier (MIL) and the University of Oslo (UiO) MOFs, which use carboxylic acids as organic ligands. Other MOF structures include PCN-224, featuring a porphyrin framework, and zeolite imidazole frameworks (ZIFs) with imidazole as the organic ligand. As the electrocatalytic ORR requires highly conductive catalyst materials, most MOF-derived catalysts must be calcined to improve graphitization and thereby enhance conductivity[94]. In this process, MOFs prepared with different organic ligands can be used to tailor the catalyst microenvironment and catalytic performance.

Carboxyl ligand-based MOF-derived catalysts

Carboxylic ligands, with their abundant coordination oxygen sites and diverse coordination modes, form stable MOFs with various metal ions, providing numerous active sites for catalysis. In addition, carboxylic acid groups have a high negative charge density and strong coordination ability with metals, further enhancing catalytic activity. Common carboxylic acid ligands include isophthalic acid, p-phthalic acid, and trimesic acid. However, catalysts derived from the pyrolysis of carboxylate-ligand-based MOFs typically form NPs, as the carboxyl oxygen atoms stably coordinate with multiple metal centers, bridging them and promoting metal-particle aggregation during pyrolysis[95].

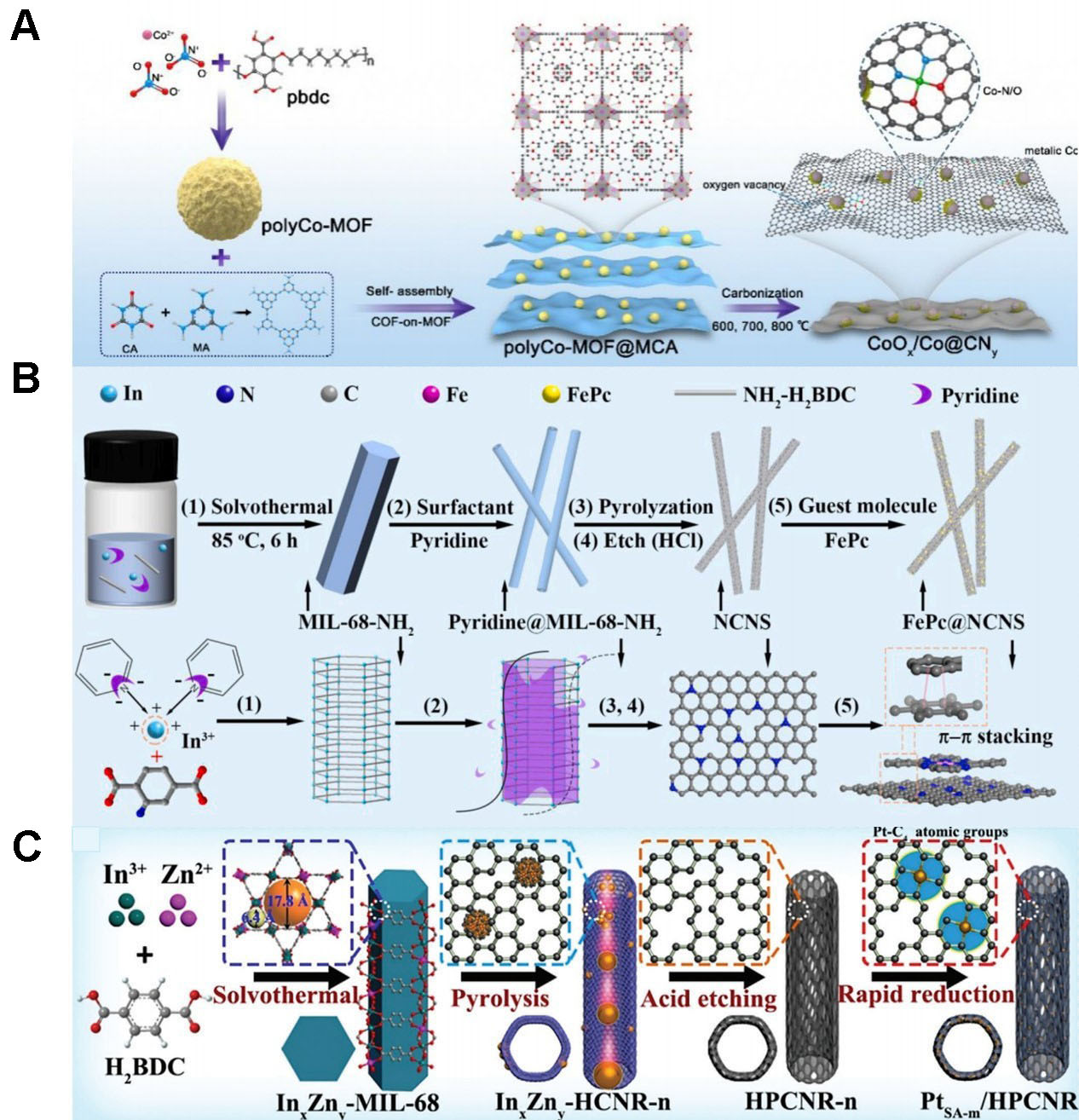

Zhang et al. synthesized a polyCo-MOF precursor using terephthalic acid as the ligand [Figure 4A][96]. The hybrid precursor polyCo-MOF@MCA, obtained through the complexation of polyCo-MOF, melamine, and cyanuric acid, was pyrolyzed at varying temperatures to yield a series of catalysts. The catalyst

Figure 4. (A) Synthesis of CoOx/Co@CNy hybrid materials (reproduced with permission from Elsevier, copyright 2023)[96]; (B) preparation of FePc@NCNS (reproduced with permission from Elsevier, copyright 2023)[97]; (C) schematic of the PtSA-m/HPCNR composite material (E-H reproduced with permission from Wiley-VCH, copyright 2023)[98]. MOFs: Metal-organic frameworks; MIL: Materials Research Institute Lavoisier.

The high specific surface area and elevated space utilization of MOF-derived catalysts have also attracted considerable research interest. For example, Yang et al. synthesized a rod-shaped indium-based

Chai et al. developed hollow porous carbon nanorods (HPCNR-n) by controlling the pyrolysis of

A review of the literature shows that MOFs with carboxylic acid ligands exhibit distinctive behavior in the ORR process[99-101]. This is attributed to the decarboxylation of carboxylic acid ligands during calcination, followed by carbonization of the organic rings to form a highly graphitized carbon support. Partial collapse of the MOF framework during decarboxylation creates a hierarchical pore structure in the carbon substrate, improving mass transfer and metal dispersion. However, the high oxygen content of carboxylic acid ligands can also promote the formation of metal oxide particles during carbonization.

Porphyrin-based MOF-derived catalysts

Porphyrins are derivatives of substituted porphyrin rings, consisting of four pyrrole units connected by methylene groups at the alpha position to form a macrocyclic conjugated structure. This configuration enables efficient electron transfer during electrochemical processes-an essential property for many applications. The ligand’s central cavity also readily chelates transition metal ions, yielding a stable M-N4 coordination mode. Upon pyrolysis of porphyrin-based MOFs, the hierarchical mesoporous/microporous structure is retained, while the M-N4 moieties are transformed into atomically dispersed metal sites anchored within the carbon matrix. These isolated metal centers act as highly efficient catalytic active sites, minimizing metal-particle agglomeration and maximizing atom utilization.

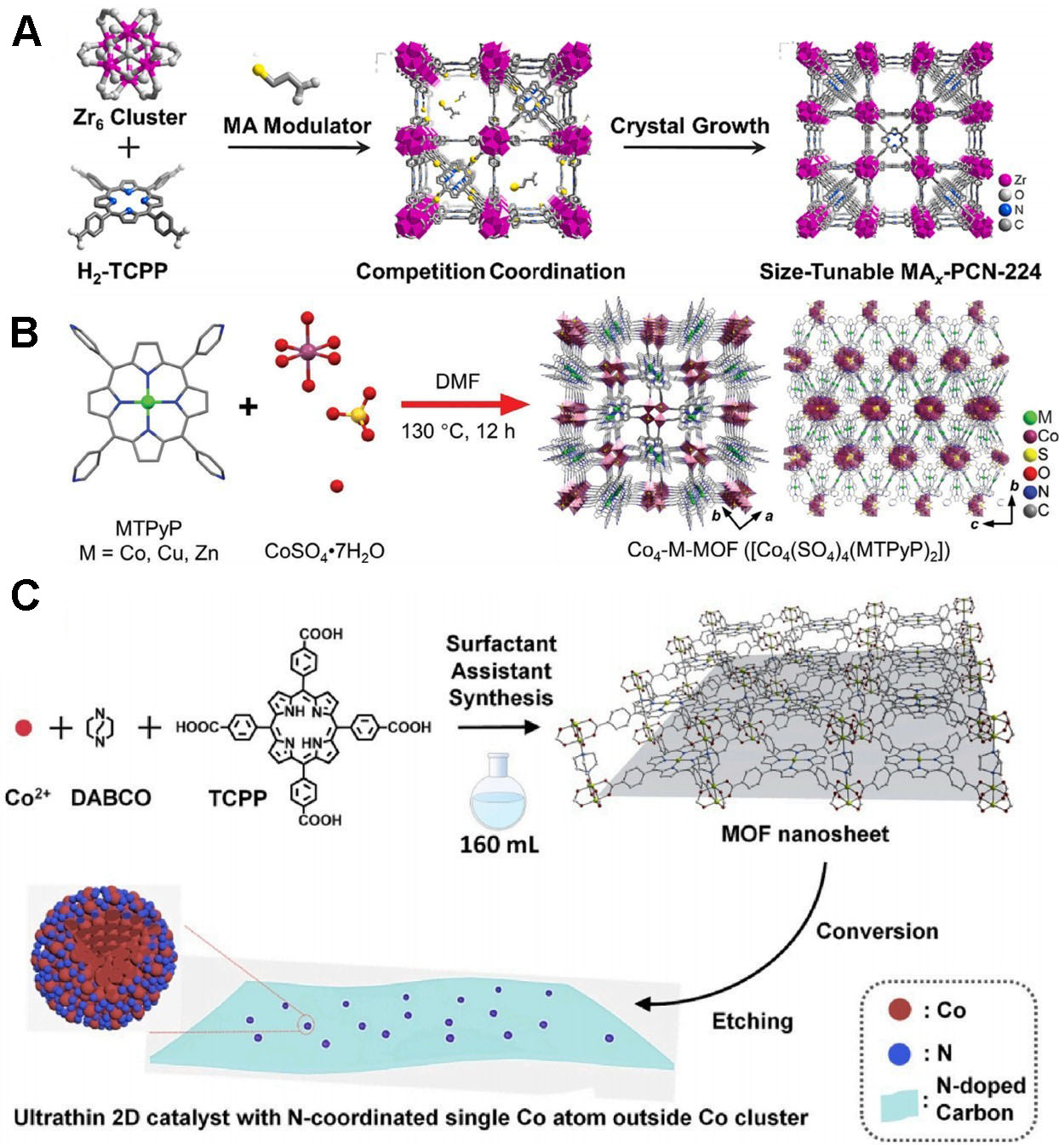

PCN-224, composed of a Zr6 cluster as the metal site and tetra(4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin (H2-TCPP) as the organic ligand, features a mesoporous structure with high periodicity, diverse topology, and numerous active defect sites, making it an attractive member of the MOF family. Zhang et al. synthesized PCN-224 using 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MA) to regulate crystal growth, adjusting the size by varying MA concentration, and obtained the corresponding MAX-NC via pyrolysis [Figure 5A][102]. The catalytic efficacy is closely tied to the number of exposed active sites; MA2-NC provided the optimal balance, delivering the best ORR performance. Subsequently, MA2-NC was impregnated with Fe single atoms (SAs), producing a catalyst with excellent activity in alkaline and acidic electrolytes.

Figure 5. (A) Schematic of MAx-PCN-224 (reproduced with permission from Elsevier, copyright 2024)[102]; (B) synthesis and crystal structure of Co4-M-MOFs (M = Cu, Co, and Zn) (reproduced with permission from Wiley-VCH, copyright 2024)[103]; (C) schematic of the Cu/NC catalyst (reproduced with permission from Elsevier, copyright 2021r)[104]. DMF: Dimethylformamide; MOFs: metal-organic frameworks.

Multicore metal clusters, common in nature, catalyze small-molecule activation reactions involving multiple electron transfers. These clusters have frequently been integrated into the organized framework structures of MOFs, demonstrating considerable potential in this context. Liang et al. performed a reaction involving metal complexes of CoSO4 and tetrakis(4-pyridyl) porphyrin (MTPyPP, M = Co, Cu, or Zn) in dimethylformamide to obtain Co4-M-MOF [Co4(SO4)4(CoTPyP)2] [Figure 5B][103]. Single-crystal data showed that the CoII at the center of the porphyrin macrocycle is coordinated via four Co-N bonds, indicating that metalloporphyrins can serve as connecting units in MOF synthesis. Replacing CoTPyP with CuTPyP or ZnTPyP yielded the corresponding Co4-Cu-MOF and Co4-Zn-MOF, confirming the versatility of this strategy. The electrocatalytic oxygen activity of Co4(SO4)4 clusters was demonstrated by testing catalysts derived from different metalloporphyrin units, with results showing that the clusters substantially contributed to the observed activity of Co4-M-MOFs.

Two-dimensional (2D) MOFs nanosheets are highly promising due to their high aspect ratio, which increases the distance between metal centers and exposes more active sites. Efficient synthesis of MOF nanosheets while preserving morphology, ensuring uniform distribution of active sites, and maintaining accessibility remains challenging. To address this, Li et al. prepared NTU-70 nanosheets with high aspect ratios using a surfactant-assisted bottom-up approach [Figure 5C][104]. The surfactants coordinate with metal ions, restricting axial growth and promoting the formation of 2D nanosheets. The resulting catalyst displayed a homogeneous distribution of Co atoms around the external regions of the Co clusters, along with notable ORR activity and enhanced durability.

As noted above, porphyrin ligands possess a high density of pyrrole rings, which provide abundant N sources under high-temperature calcination, promoting the formation of M-Nx sites[105,106]. The oxygen atoms in the porphyrin ring also favor the formation of metal oxides and the aggregation of NPs during calcination. Consequently, catalysts derived from these ligands typically contain NPs and single atoms.

Imidazole-based MOF-derived catalysts

ZIFs are MOFs synthesized with imidazole compounds as ligands. The imidazole moiety is a conjugated aromatic system with dual N coordination sites. The N atoms in the imidazole ring readily form stable M-N coordination bonds with transition metals, enabling homogeneous dispersion of metal ions within the MOF framework. In dimethylimidazole ligands, the nitrogen atoms restrict metal-atom migration through a “coordination capture” mechanism, mitigating agglomeration and producing atomically or near-atomically dispersed metal sites, thereby greatly enhancing atomic utilization efficiency. Upon pyrolysis, N atoms from the imidazole ligands remain in the carbon skeleton, yielding a highly N-doped carbon layer. Pyridinic- and pyrrolic-N species act as active sites directly involved in ORR processes (adsorption and activation of O2), while graphitic N modulates the carbon matrix’s electronic structure, increasing charge density and thus electrical conductivity[107]. The methyl groups (-CH3) of dimethylimidazole provide a carbon source during pyrolysis and, through an “electronic induction effect”, fine-tune the electron cloud density of adjacent N atoms, optimizing their interaction with metal centers. These intrinsic structural features of imidazole-based MOFs are particularly advantageous for ORR applications[108].

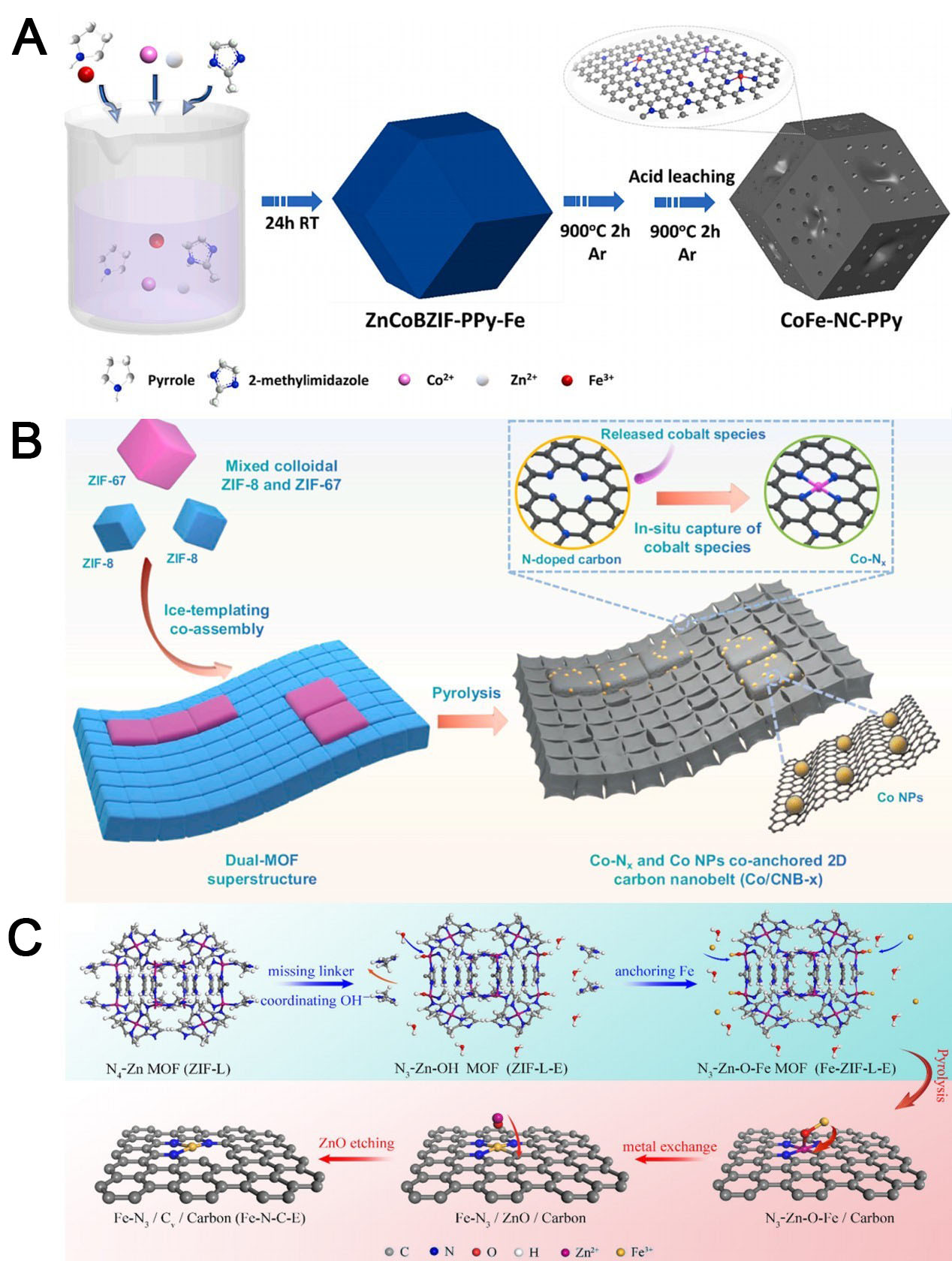

These characteristics are exemplified in the CoFe NC polypyrrole (PPy) catalyst developed by Nguyen et al. [Figure 6A][109]. The researchers combined ZIFs and PPy in a one-pot synthesis, producing a non-noble metal ORR catalyst in which the active components were uniformly distributed during MOF crystallization and pyrrole polymerization. The catalyst exhibited a multi-stage porous structure, a large surface area

Figure 6. Synthetic procedures of (A) the CoFe-NC-PPy electrocatalyst (reproduced with permission from Elsevier, copyright 2024)[109] and (B) the Co/CNB-x catalyst (reproduced with permission from Elsevier, copyright 2023)[110]; (C) construction of Fe-N-C-E (Reproduced with permission from the Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society, copyright 2024)[111]. N-C-E: Metal-nitrogen-carbon; ZIFs: zeolite imidazole frameworks; MOFs: metal-organic frameworks.

Using an ice-template co-assembly method driven by van der Waals forces, Yang et al.[110] designed an advanced carbon superstructure with a customized atomic-scale metal configuration and optimized mass transfer performance for energy conversion applications. This bimetallic organic framework superstructure comprised ZIF-8 and ZIF-67 nanocubes [Figure 6B]. Cobalt monoatoms and NPs were then anchored onto a 2D N-doped rice nanoribbon, producing an excellent ORR electrocatalyst. After pyrolysis, the resulting catalyst contained synergistically combined atomically dispersed Co SAs and Co NPs. The 2D carbon nanobelts possessed a layered porous structure with interconnected hollow carbon nanocubes, increasing active-site exposure, enhancing mass transfer, and accelerating reaction kinetics. The optimized catalyst (CO/CNB-10) showed a higher E1/2 (0.888 V) than commercial Pt/C, along with exceptional stability and methanol resistance. Integrated into a ZAB, it achieved a peak power density of 179 mW cm-2, outperforming comparable Pt/C-based products.

Using a water-etching technique, Li et al.[111] created missing-connector-type defects in leaf-like ZIF (ZIF-L) [Figure 6C]. Fe3+ was chemically anchored to coordination-unsaturated Zn-N3 sites, forming an N3-Zn-O-Fe structure. During pyrolysis, Fe3+ replaced Zn2+ via metal exchange, producing an asymmetric Fe-N3 configuration. Simultaneously, endogenous ZnO corroded the surrounding carbon matrix, generating carbon vacancies (CVs) that promoted directional construction of Fe-N3 sites. The resulting Fe-N3/CV catalyst achieved excellent E1/2 values in alkaline and acidic media (0.92 and 0.77 V, respectively). This linker-free auxiliary synthesis strategy demonstrates the versatility of multiple MOF precursors and iron sources and enables precise atomic-scale fabrication of high-performance M-N-C electrocatalysts for energy conversion applications.

Imidazole ligands have been shown to release a substantial N-sites during high-temperature calcination[112,113]. Because of their low oxygen content, these MOFs tend to form metal particles rather than metal oxide particles. Additionally, Zn, a common metal used to form MOFs with imidazole ligands, has a low boiling point, leading to the creation of a substantial number of metal vacancies during calcination. These vacancies, in turn, facilitate the formation of M-Nx sites. Consequently, imidazole ligand-derived catalysts can be readily converted into single-atom catalysts.

Nitrogenous heterocycle-based MOF-derived catalysts

Like the traditional ligands mentioned above, MOFs constructed from nitrogen-containing heterocyclic ligands possess unique ORR properties that are governed by ligand chemistry, metal node coordination, and structural porosity. Nitrogen-containing heterocyclic ligands coordinate with transition metals (Fe, Co, and Mn) to form catalytically active M-Nx sites mimicking the Fe-Nx centers of enzyme catalysts. Such active sites promote oxygen adsorption, O-O bond cleavage, and the four dominant electron transfer pathways. The electron-donating properties of nitrogen atoms have been shown to optimize the d-band electronic state in the metal center, thereby reducing the potential barrier of key steps such as *OH desorption, whereas the conjugated π-system in the ligand enhances charge delocalization and electron transfer dynamics. The enhanced stability of nitrogen-rich MOFs is attributed to robust m-n bonding. In addition, an N-doped carbon matrix, which cooperatively improves the conductivity and corrosion resistance of the MOFs, is embedded in the metal sites after pyrolysis[114]. These materials effectively function over a wide range, spanning acidic to alkaline conditions. Protonated nitrogen sites stabilize the intermediates in acidic media, while the M-Nx centers directly drive the ORR in alkaline environments. The inherent challenges (low conductivity and durability) are overcome by hybrid or protective packaging strategies with conductive substrates.

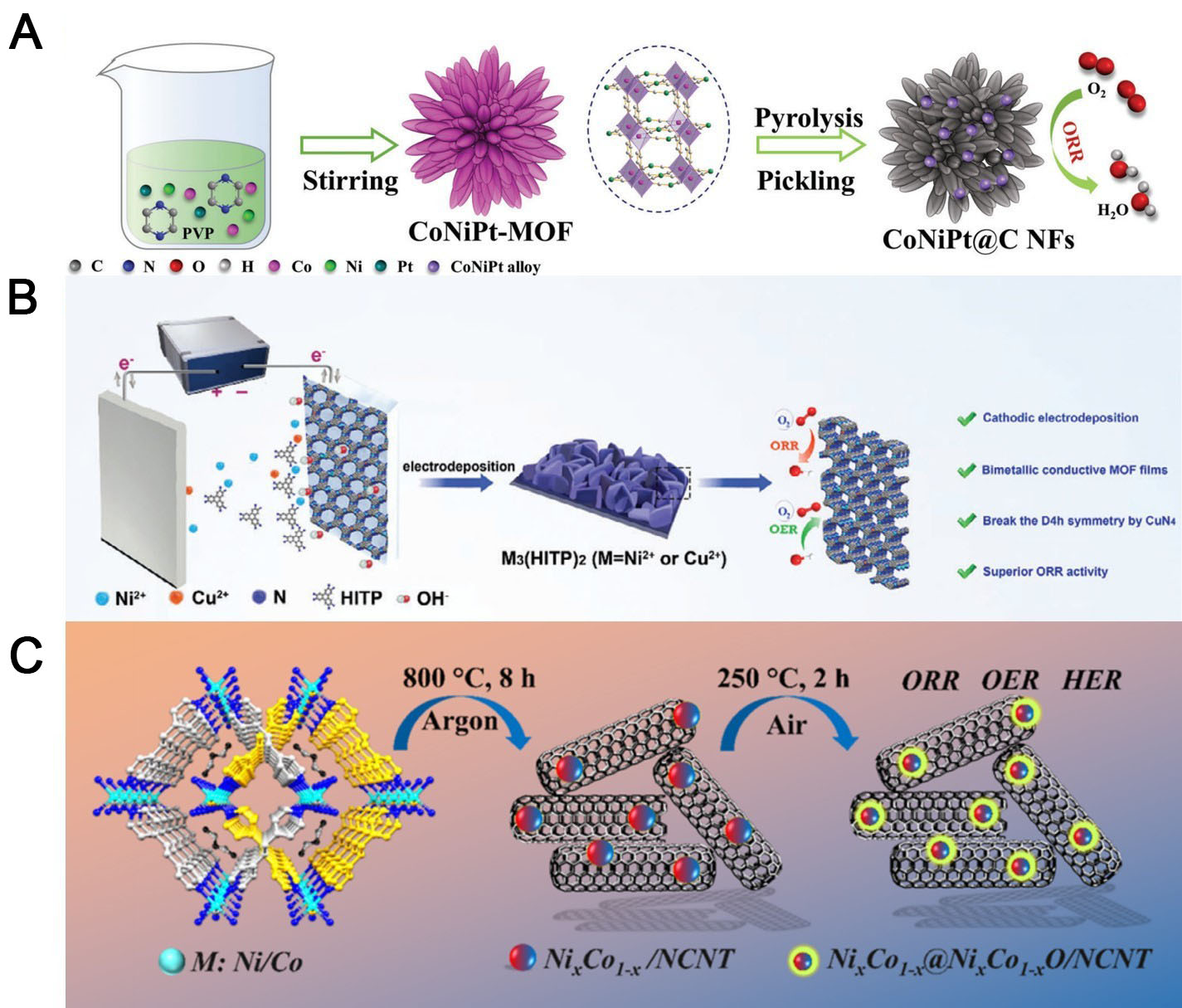

Pan et al. synthesized Hofmann-type MOFs with pyrazine as the ligand [Figure 7A][115]. The pyrolysis process formed a nanoflower-like segregation alloy, which was subsequently loaded into nitrogen-doped porous carbon. By precisely modulating the pyrolysis and acid-treatment parameters, the researchers optimized the composition of CoNiPt@C NFs to 15%. The resulting catalyst exhibited a remarkable E1/2 of 0.93 V under alkaline conditions. The hierarchical nanoflower structure exposed numerous active sites and accelerated the transmission of the intermediates, while the microstructure synergistically optimized the adsorption energy of the ORR intermediates. When integrated into ZABs with RuO2, the test performance is also superior to that of Pt/C-based catalysts.

Figure 7. (A) Synthesis of CoNiPt@C NFs catalysts (reproduced with permission from Wiley-VCH, copyright 2023)[115];

Liu et al. developed high-performance bimetallic conductive MOF as electrocatalysts for the ORR process in ZABs [Figure 7B][116]. A room-temperature electrochemical cathodic deposition method yielded continuous 2D Ni/Cu-HITP MOF films without polymeric binders, circumventing the intrinsic conductivity limitations and aggregation issues of conventional MOFs. The Eonset of the optimized Ni2.1Cu0.9(HITP)2 reached 0.93 V. In aqueous ZABs, the catalyst delivered exceptional performance metrics (specific capacity = 706.2 mAh g-1) and remarkable durability over 1,250 charge/discharge cycles. Besides enabling the effective design of binder-free conductive MOF electrodes, Liu et al.’s[116] study provides fundamental insights into bimetallic coordination effects for advanced energy storage applications.

Jena et al. developed the triply-functional electrocatalyst NixCo1-x@NixCo1-xO/ N-doped carbon nanotubes (NCNTs) via pyrolysis followed by calcination of a bimetallic (Ni, Co) MOF [Figure 7C]. This catalyst, consisting of core-shell bimetallic NPs (with an NixCo1-x alloy core and an NixCo1-xO oxide shell) stabilized on the NCNTs, achieves superior electrocatalytic activities for multiple reactions[117]. During the ORR process, the alloy core, oxide shell, N-doped carbon matrix, Co-to-Ni charge transfer, and oxygen vacancies synergistically yield an excellent half-wave potential (E1/2 = 0.87 V). Density functional theory (DFT) calculations clarified the roles of the Ni active center and Co-induced electron modulation. When implemented in a ZAB, the catalyst yielded a high specific capacity (746 mAh g-1), a high power density

As the core components of MOFs, ligands largely influence the active centers of the derived single-atom, nanocluster, or porous-carbon matrix catalysts. This impact is attributable to the chemical structure, electronic properties, and pyrolysis behavior of the ligands. A comprehensive review of the extant literature revealed that ligands with high nitrogen content (such as imidazole) provide more nitrogen coordination sites than other ligand types, facilitating the formation of single-atom catalysts, whereas ligands with elevated oxygen content (such as carboxylic acid) tend to form NP catalysts during the calcination process. Ligands with elevated nitrogen and oxygen contents (such as porphyrin ligands) tend to form catalysts with coexisting single atoms and NPs. The catalytic active center can be selectively regulated through ligand modification and design.

MOF-derived catalysts have demonstrated unique potential for the ORR. Some processes can yield kilogram-level catalysts and the catalytic performances of MOF-derived catalysts are comparable to those of commercial Pt/C catalysts. Furthermore, the effectiveness and reliability of MOF-derived catalysts have frequently been demonstrated in practical batteries. As MOFs can effectively catalyze chemical conversion reactions, nonprecious metal catalysts achieve comparable performance to their precious metal counterparts. This advancement promises high-performance, cost-effective applications in various fields of chemistry. Tables 1 and 2 report the catalytic performance data of MOF-based catalysts with different ligands and MOF-based catalysts used in different energy conversion devices, respectively. Remarkably, most of these catalysts outperform commercial Pt/C, underscoring their considerable promise in future applications. Catalysts derived from imidazole-based MOFs deliver the highest half-wave potential performance and ZABs are most commonly employed in energy conversion devices. Many catalysts for PEMFCs have reached or approached the 2025 target of the US Department of Energy (DOE).

Summary of the reported performance data of MOF-based ORR electrocatalysts

| Ligand | Catalyst | ORR condition | E 1/2 (V vs. RHE) | Ref. |

| Carboxylic | FePc@NCNS | Alkaline | 0.904 | [97] |

| Co4N@NCNT-900 | Alkaline | 0.875 | [118] | |

| FePc@NC-1000 | Alkaline | 0.86 | [119] | |

| Fe@NSC | Alkaline | 0.87 | [100] | |

| Fe0.05-N@ MOF | Alkaline | 0.86 | [101] | |

| L/Fe-NC | Acid | 0.82 | [120] | |

| Fe/I-N-CR | Alkaline | 0.915 | [99] | |

| Porphyrin | MA3-NC(Fe)-2 | Alkaline | 0.824 | [102] |

| Co4-Co-MOF | Alkaline | 0.83 | [103] | |

| Co@N-C700 | Alkaline | 0.78 | [104] | |

| CuNC-1000 | Alkaline | 0.85 | [121] | |

| CoNiFe0.08-NC@p-NCNTs | Alkaline | 0.811 | [122] | |

| CoSA-AC@SNC | Alkaline | 0.86 | [105] | |

| Imidazole | CoFe-NC-PPy | Alkaline | 0.915 | [109] |

| Co/CNB-10 | Alkaline | 0.888 | [110] | |

| Fe-N-C-S | Alkaline | 0.92 | [111] | |

| Co-NCR | Alkaline | 0.88 | [123] | |

| FeCo@NC-II | Alkaline | 0.907 | [124] | |

| FeCu-HCNFs | Alkaline | 0.884 | [112] | |

| MOF CoTe2/MnTe2 | Alkaline | 0.81 | [125] | |

| [email protected] | Alkaline | 0.85 | [126] | |

| Nitrogenous | 15% CoNiPt@CNFs | Alkaline | 0.93 | [115] |

| Ni2.1Cu0.9(HITP)2 | Alkaline | 0.76 | [116] | |

| NixCo1-x@NixCo1-xO/NCNT | Alkaline | 0.79 | [117] | |

| Rbf-Ni-MOF | Alkaline | 0.84 | [127] | |

| Ni3Fe-NCNTs-800 | Alkaline | 0.862 | [128] |

Reported performance data of MOF-based ORR electrocatalysts in different energy conversion devices

| Device | Catalyst | Power density | Durability | Ref. |

| PEMFC | OP-Fe-NC | 937 mW cm-2 (2 bar) | 27.8% loss (240 h) | [129] |

| Mn-N-C-HCl-800/1100 | 600 mW cm-2 (1 bar) | 20% loss (16 h) | [130] | |

| CoMn/NC | 970 mW cm-2 (1 bar) | Negligible loss (24 h) | [85] | |

| Fe-Al-RNC | 1.05 W cm-2 (1.5 bar) | 19.7% loss (100 h) | [131] | |

| Fe-AC-CVD | 535 mW cm-2 | 3.9% (30,000 cycles) | [18] | |

| 700 CO2 Fe-NC | 670 mW cm-2 | 38.6% (100 cycles) | [132] | |

| AEMFC | CoFe-NC-PPy | 352 mW cm-2 | / | [109] |

| Fe-NC-1000 | 149 mW cm-2 | / | [133] | |

| ZAB | CoMn-N/S-C | 203 mW cm-2 | 350 h (5 mA cm-2) | [85] |

| Co-N-C/CNF | 159 mW cm-2 | > 100 h (10 mA cm-2) | [7] | |

| Co3Fe7/NC-50 | 248.1 mW cm-2 | 1,000 h (5 mA cm-2) | [40] | |

| Co@N-CNTs/NSs | 142.3 mW cm-2 | 421 cycles (5 mA cm-2) | [89] | |

| Co/CNB-10 | 179 mW cm-2 | 90 h (10 mA cm-2) | [110] | |

| CoNiPt@C | 172 mW cm-2 | 70 h (10 mA cm-2) | [115] | |

| Ni2.1Cu0.9(HTP)2 | 41.5 mW cm-2 | 12,500 min (5 mA cm-2) | [116] | |

| FeSAs-UNCNS | 305.7 mW cm-2 | > 180 h (5 mA cm-2) | [134] | |

| FeH-N-C | 225 mW cm-2 | > 1,200 h (5 mA cm-2) | [135] |

MOF-DERIVED CATALYSTS WITH DIFFERENT ACTIVE CENTERS

Metal ions or clusters are integral components of MOF frameworks, as they support the formation of porous architectures and regulate their pore sizes and topological structures. The type of active center, existence form (e.g., single atoms, dual atoms, clusters, or NPs), and electronic structure of the metal species play decisive roles in the catalytic performance (e.g., activity, selectivity, stability) of a MOF-derived catalyst[135]. First, metals are direct active centers in catalytic reactions and their atomic-level structures (e.g., coordination environment, valence state) dictate the reactant adsorption behavior and reaction pathways[136,137]. Second, the d-band center, electron density, and orbital hybridization of metals and their ligands directly influence the catalytic properties. Finally, the strong interaction between the metal and the MOF-derived carbon matrix (typically containing heteroatoms such as N and O) affects the metal dispersion and electronic structures[138].

MOF-derived single-atom catalysts

Owing to the porous nature of MOF materials, the types of metal catalysts derived from a given MOF are correlated with both the MOF itself and the metal content within its pores. The metal content in the MOFs and the reaction conditions can be controlled to obtain relatively pure single-atom catalysts (SACs), in which a single atom site is the active center of catalysis[139-143]. Smaller metal particles are preferred for heterogeneous catalysis because they provide a higher proportion of surface atoms than larger particles, thereby improving both the atomic utilization efficiency and catalytic activity[144]. The atomic utilization efficiency of SACs can potentially reach 100%, far exceeding the capabilities of traditional catalysts[145,146]. Transition metal catalysts loaded on nitrogen-doped carbon supports, a subcategory of SACs, have demonstrated remarkable potential for the ORR and are regarded as an optimal alternative to conventional Pt/C[147,148].

MOF-derived Fe single-atom catalysts

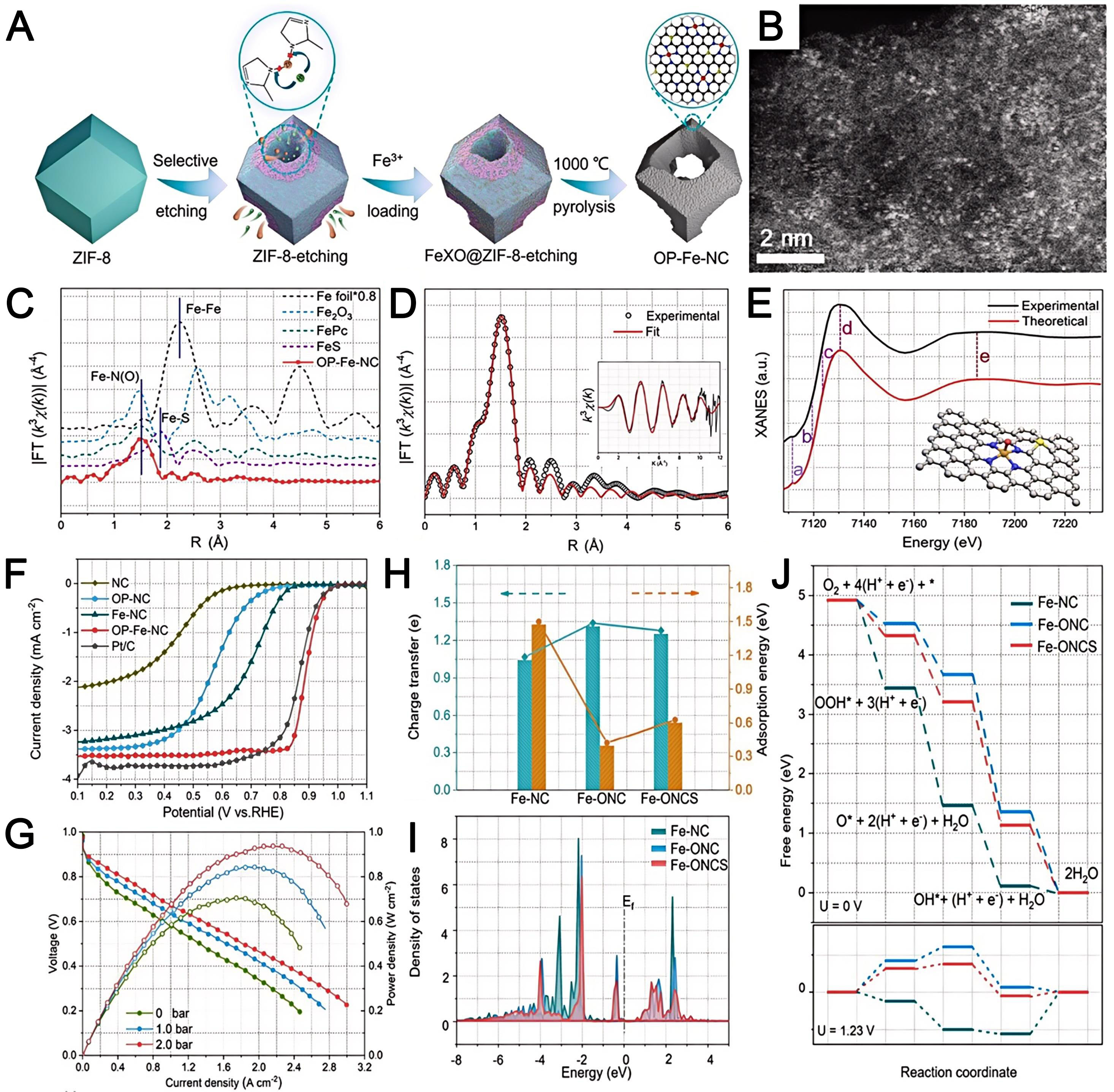

The isolated Fe atoms in MOF-derived single-atom Fe catalysts derive from two sources: inherent Fe nodes within the MOF structure, and externally adsorbed Fe precursors. The latter are anchored on the porous MOFs architecture and subsequently transformed into isolated single atoms through postsynthetic treatments. By virtue of their elevated activity, minimal cost, and four-electron selectivity, Fe SACs have been extensively researched as potential alternatives to noble metal catalysts[149,150]. For instance, Li et al. prepared OP-Fe-NC through chelate-assisted selective etching with xylenol orange and opening of the ZIF material [Figure 8A][129]. Interconnected openings in these carbon materials facilitate the diffusion and mass transfer of oxygen in the catalyst layer. High-angle annular dark field-scanning TEM (HAADF-STEM) revealed abundant iron sites on the carbon surface [Figure 8B]. The coordination around the single Fe site was analyzed by R-space fitting of the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) data

Figure 8. (A) Schematic and (B) HAADF-STEM image of OP-Fe-NC; (C) Fourier transformed EXAFS spectra of OP-Fe-NC catalysts; (D) corresponding quantitative fittings of the EXAFS spectra in R space. Inset shows the corresponding EXAFS fitting in K space; (E) Comparison between the experimental and theoretical X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra. Inset is a schematic of the interfacial model of OP-Fe-NC; (F) LSV curves; (G) polarization and power density curves of H2-O2 fuel cells with OP-Fe-NC and

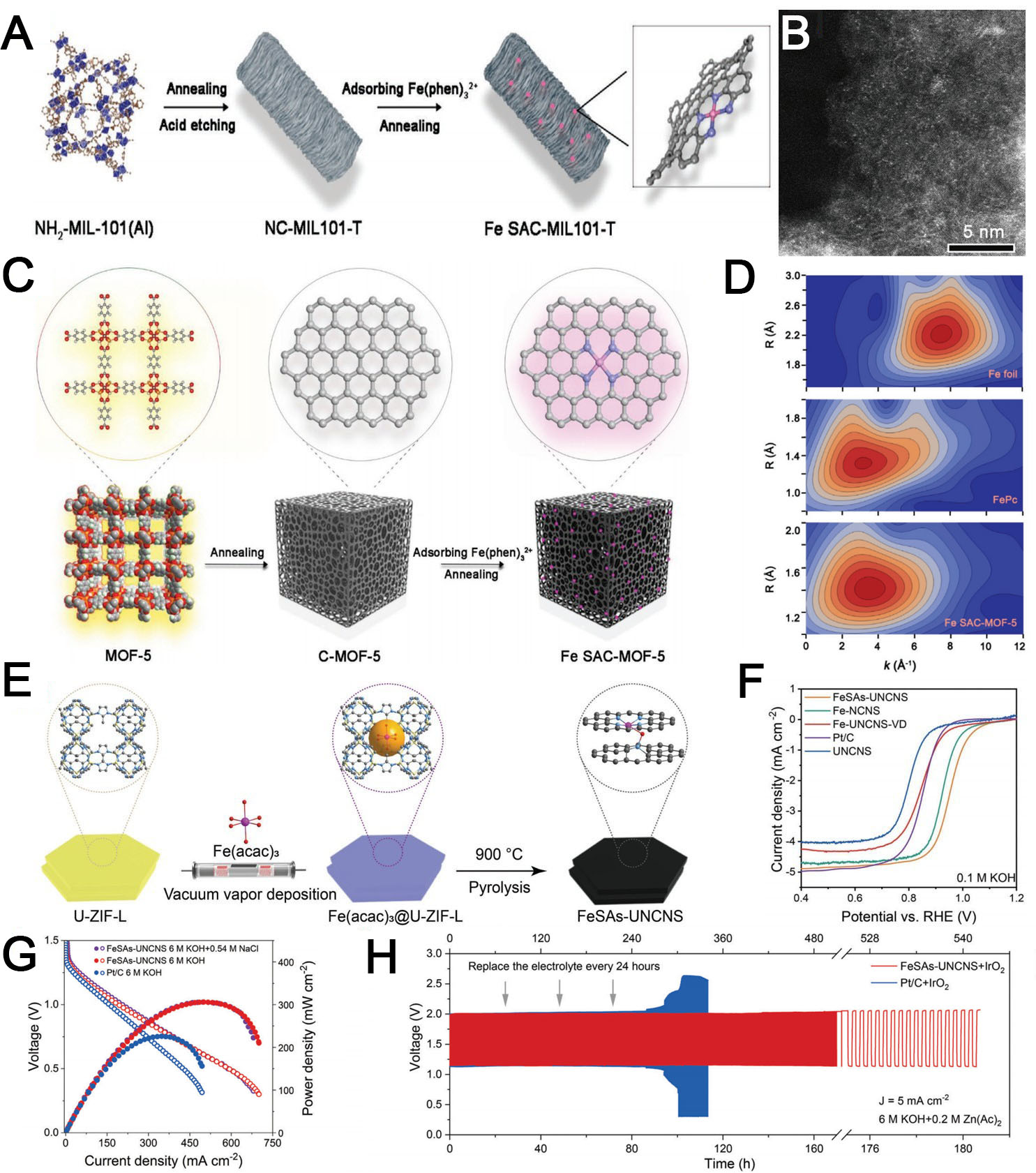

To overcome the limitations of conventional microporous MOF-derived catalysts, Xie et al. pyrolyzed

Figure 9. (A) Schematic of Fe SAC-MIL101-T and (B) aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM image of Fe SAC-MIL101-1000 (A and B reproduced with permission from Wiley-VCH, copyright 2021)[151]; (C) synthesis of the Fe SAC-MOF-5 catalyst; (D) wavelet-transformed

Xie et al. obtained a high-performance Fe SAC-MOF-5 from MOF-5-derived carbon for the ORR in PEMFCs [Figure 9C][152]. Pyrolysis of Zn-based MOF-5 with a three-dimensional microporous cubic structure yielded a highly porous carbon support with a Brunauer-Emmet-Teller specific surface area of 2,751 m2 g-1 and a large external surface area (1,651 m2 g-1). Applying a ligand-mediated approach, the authors anchored atomically dispersed FeN4 sites (Fe loading 2.35 wt%) on the carbon matrix with no Fe aggregation [Figure 9D]. The Fe SAC-MOF-5 catalyst delivered a half-wave potential of 0.83 V. When incorporated into an H2-O2 PEMFC under 0.2 MPa, the peak power density reached 0.84 W cm-2. This high performance was attributed to the hierarchical porosity of SAC-MOF-5, which simultaneously enables dense FeN4-site formation and efficient mass transport. MOF-5-derived carbons were highlighted as superior supports that maximize the number of accessible active sites in SACs, providing insights for designing high-performance Platinum Group Metals (PGM)-free electrocatalysts through MOF precursor engineering.

Applying a novel vacuum-vapor deposition strategy, Yang et al. synthesized FeSAs-ultrathin nitrogen-doped carbon nanosheets (UNCNS) with densely accessible active sites in Fe-N4O for high-performance ZABs [Figure 9E][134]. The iron salt is sublimated into the micropores of the ultrathin ZIF-L nanosheet precursors under vacuum conditions, effectively preventing iron aggregation while achieving high Fe loading

MOF-derived Co single-atom catalysts

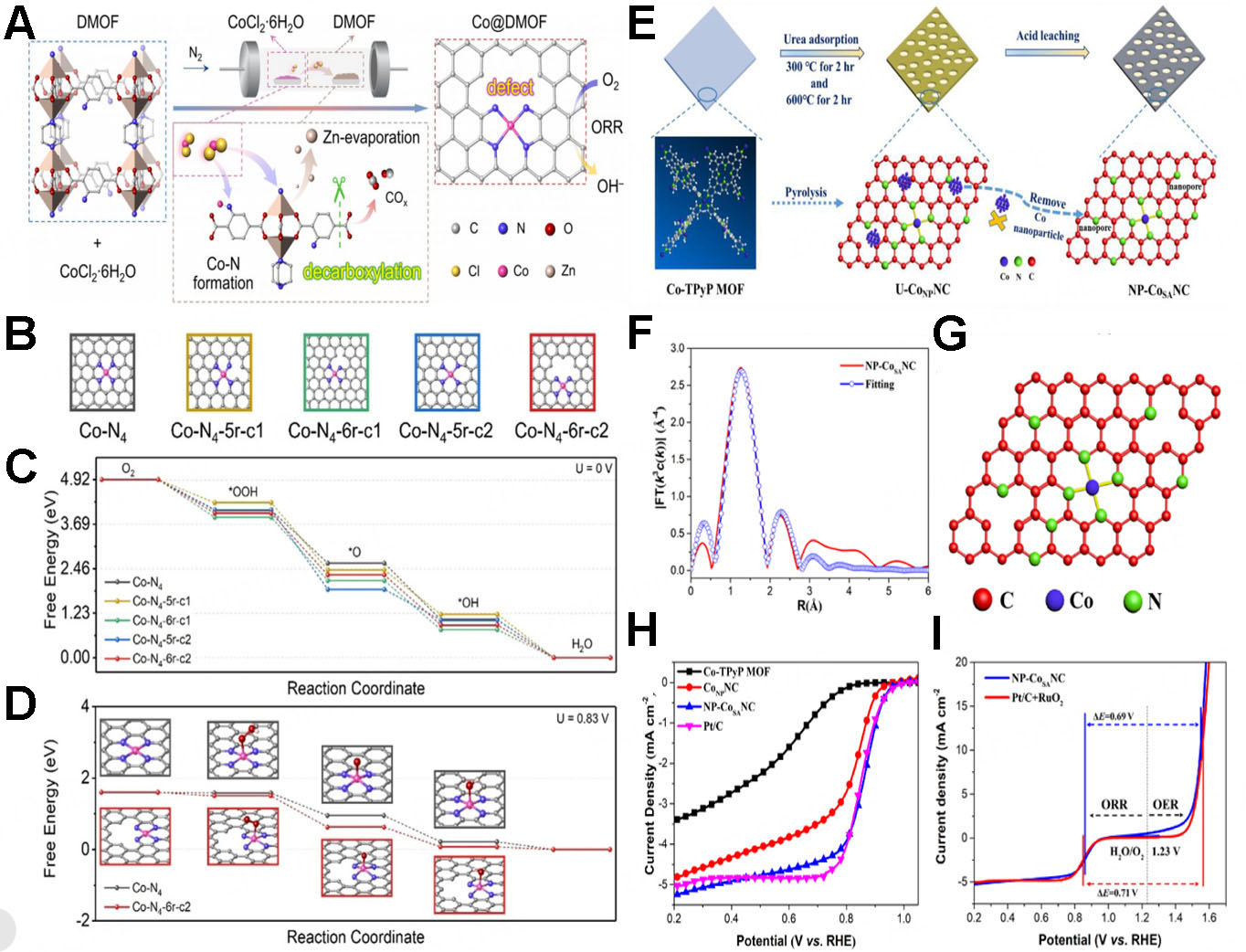

To enhance the intrinsic ORR activity of Co SACs, Yuan et al. introduced defects through decarboxylation of MOF-derived carbon supports [Figure 10A][153]. Using a mixed-ligand carboxylate/amide MOF (DMOF) as a precursor, the researchers synthesized defect-rich Co SACs via pyrolysis coupled with gas-phase

Figure 10. (A) Preparation and proposed formation mechanisms of Co@diamondized MOF; (B) five possible models of atomic Co-N4 configurations with different defect degrees; free energy diagrams of the models in (B), calculated at (C) U = 0 V (vs. SHE) and (D) U = 0.83 V (A-D reproduced with permission from Wiley-VCH, copyright 2021)[153]; (E) Preparation, (F) EXAFS R-space fitting curve, and (G) model of CoN4 configuration in NP-CoSANC; (H) LSV curves, (I) Overall polarization curves. (E-I reproduced with permission from Elsevier, copyright 2023)[154]. MOF: Metal-organic framework; EXAFS: extended X-ray absorption fine structure; LSV: linear sweep voltammetry.

Rong et al. derived a high-performance NP-CoSA/NC catalyst from a Co-TPyP MOF for ORR and ZAB applications [Figure 10E][154]. By introducing urea as an additional nitrogen source during pyrolysis, they successfully inhibited cobalt aggregation while creating a nanoporous structure, achieving a high cobalt loading (6.4 wt%) within atomically dispersed CoN4C active sites across nitrogen-doped carbon [Figure 10F and G]. The optimized catalyst demonstrated excellent ORR performance with a half-wave potential of

Others

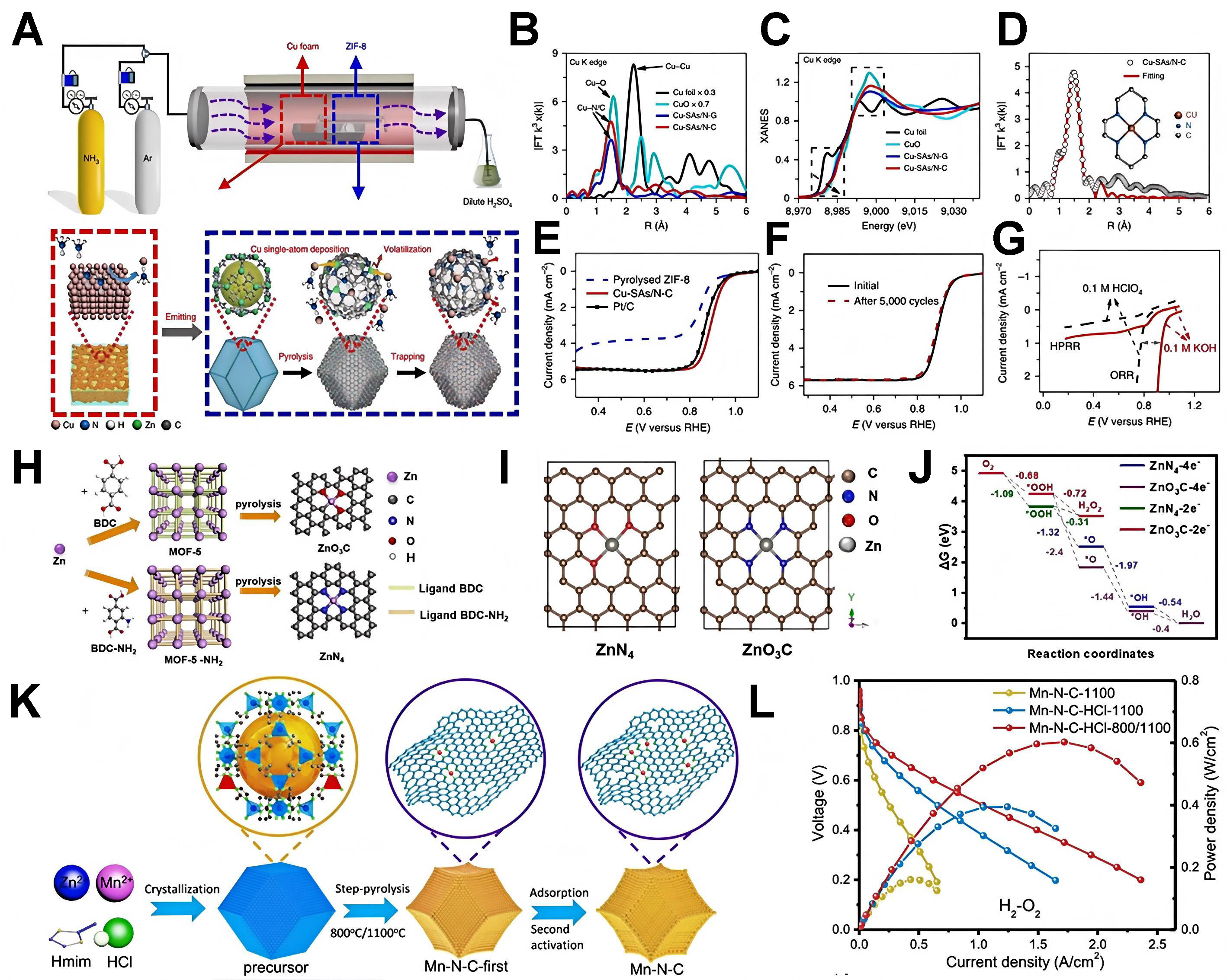

Qu et al. presented a gas-migration method that directly converts bulk copper into isolated Cu-SAs/N-C

Figure 11. (A) Schematic and reaction mechanism of Cu-SAs/N-C; (B) K3-weighted χ(k) functions of EXAFS spectra; (C) copper K-edge XANES spectra of Cu-SAs/N-C; (D) EXAFS fitting curve of Cu-SAs/N-C. Inset shows the proposed Cu-N4 coordination environment. LSV curves of (E) Pt/C, Cu-SAs/N-C and pyrolyzed ZIF-8 and (F) Cu-SAs/N-C before and after 5,000 cycles of accelerated durability testing; (G) Comparison between the HPRR and ORR. Reactions were performed in N2-saturated electrolyte (3.5 mM H2O2) (A-G reproduced with permission from Springer Nature, copyright 2018)[155]; (H) Schematic showing the preparation process of ZnO3C and ZnN4 electrocatalysts; (I) optimized geometric model of Zn single atoms in ZnN4 and ZnO3C; (J) Free energy diagrams of the 2e- and 4e- ORR pathways on ZnO3C and ZnN4 at 0 V vs. RHE (H-J reproduced with permission from Wiley-VCH, copyright 2021)[156]; (K) Aqueous synthesis scheme of Mn-N-C catalysts and (L) fuel-cell performances of different catalysts under H2-O2 (K and L reproduced with permission from the American Chemical Society, copyright 2020)[130]. EXAFS: Extended X-ray absorption fine structure; SAs: single atoms; ZIF: zeolite imidazole frameworks; ORR: oxygen reduction reaction; XANES: X-ray absorption near-edge structure; HPRR: hydrogen peroxide reduction reaction.

By engineering the coordination environment, Jia et al. precisely controlled the selectivity of Zn catalysts for the ORR pathway [Figure 11H][156]. They synthesized two distinct Zn single-atom catalysts-ZnO3C

The aqueous synthesis method of Chen et al. creates Mn-N-C catalysts for the ORR in PEMFCs

In summary, MOFs are ideal precursors for the synthesis and fine-tuning of SACs. In particular, they provide a designable coordination environment, multilevel porosity, and strong metal anchoring ability. For instance, the ligands in MOFs facilitate the formation of stable M-N/O sites, while the MOFs themselves provide both intrinsic metal sites and extrinsic metal sites introduced through their porous structures. In addition, the metal species are well isolated within the highly uniformly dispersed pores of MOFs, effectively preventing metal agglomeration. Subsequent modification of the skeleton can further enhance the activity and stability of defect engineering or heteroatom doping. Saccharides derived from pyrolytic MOFs (such as Fe-N-C materials[5]) confer high conductivity and durability, achieving catalysts with performances approaching that of Pt/C in fuel cells. However, precise synthesis, long-term stability under harsh conditions, and scalable production are challenging tasks requiring advanced characterization, protective packaging, and template-free synthesis strategies. Future work should focus on clarifying the structure-activity relationship through DFT simulations and on bimetallic site engineering to promote MOF-based SACs for sustainable energy applications.

MOF-based dual-atom catalysts

The synthesis of MOF-based dual-atom catalysts requires precise control over the metal content in the precursor MOFs, most of which are derived from the ZIF-8 system. One strategy leverages the porous nature of MOFs by adsorbing small molecules capable of chelating dual metal atoms prior to pyrolysis. By controlling pyrolysis conditions, the chelated metal pairs can be retained as isolated dual-atom sites. Chelation of identical metals produces homonuclear dual-atom configurations, while chelation of different metals yields heteronuclear sites. Alternatively, partial substitution of the original MOF metal nodes with a secondary metal can generate heteronuclear dual-atom sites after pyrolysis. This approach directly exploits the structural tunability of MOF nodes to preorganize the desired metal pairs.

Homologous dual-atom catalysts

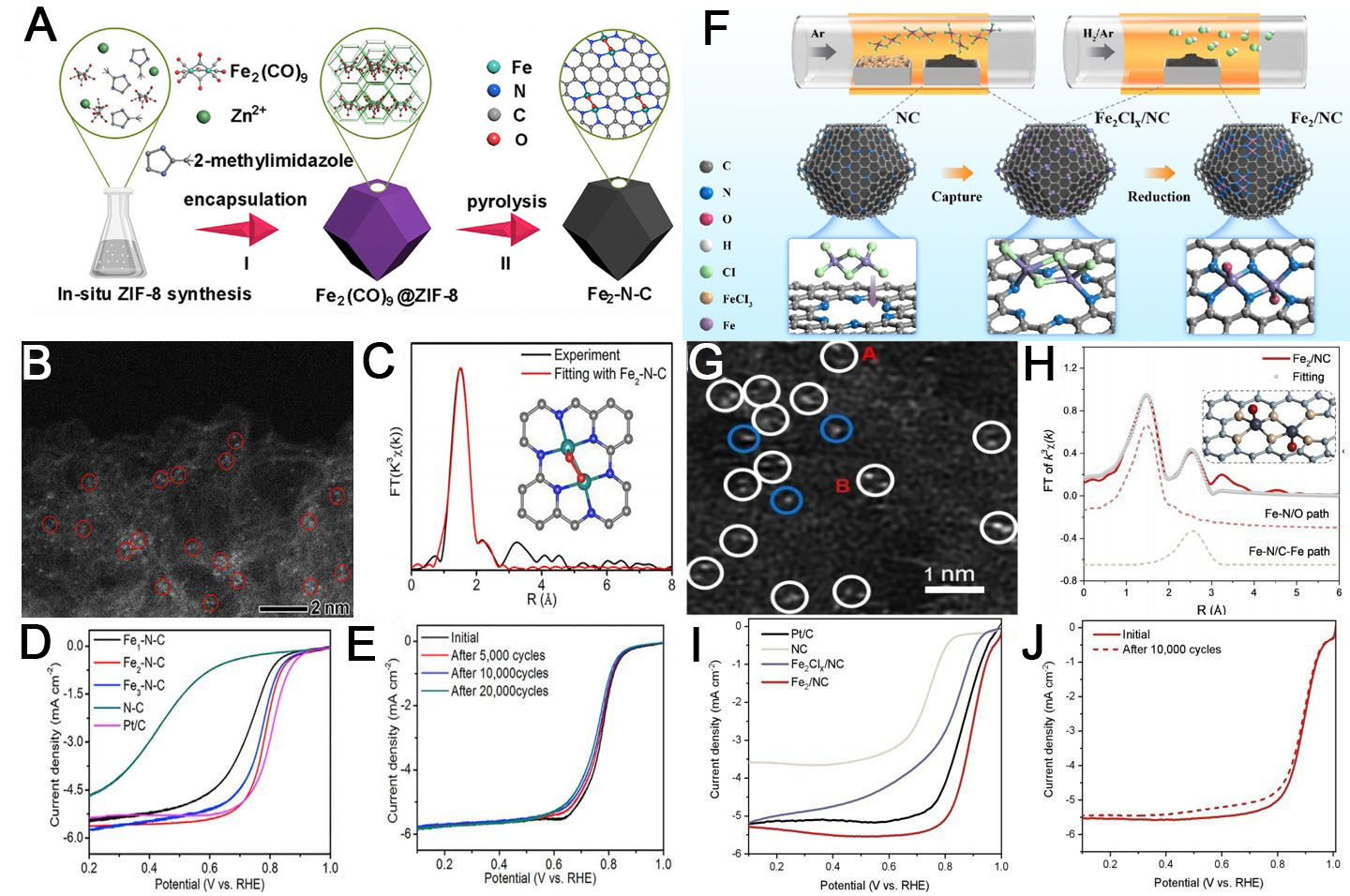

Similar to the synthesis of SACs, controlling the metal content in MOF materials can yield relatively pure dual-atom catalysts[157]. Ye et al. developed a novel method to enhance ORR performance by precisely controlling Fe atoms anchored on nitrogen-doped carbon supports [Figure 12A][158]. Fe-containing precursors were encapsulated within ZIF-8 and pyrolyzed, producing Fe clusters with specific atomic configurations. HAADF-STEM and X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (XAFS) analyses revealed that Fe2 clusters exhibited optimal peroxo-like O2 adsorption configurations and modulated the N-species distribution in the carbon matrix [Figure 12B and C]. Electrochemical tests showed that Fe2-N-C achieved an E1/2 of 0.78 V, approaching that of commercial Pt/C, with remarkable durability (only 20 mV decay after 20,000 cycles). Mechanistic studies indicated that Fe2 clusters facilitated O2 activation through enhanced electron transfer and optimized support properties [Figure 12D and E].

Figure 12. (A) Schematic showing the two-step synthesis of Fe2-N-C; (B) HAADF-STEM images and (C) K3-weighted χ(k) function of the EXAFS spectra of Fe2-N-C; (D) LSV curves in O2-saturated 0.5 M H2SO4 solution at a sweep rate of 10 mV s-1 and a rotation speed of

In another study, Yan et al. synthesized dual-atom Fe catalysts (Fe2/NC) with a precisely controlled Fe-Fe distance of 0.3 nm from Fe2Cl6 vapor precursors[159]. Sublimation of FeCl3 produced Fe2Cl6 dimers anchored on N-doped carbon supports. Subsequent hydrogen treatment removed chlorine ligands, yielding atomically dispersed Fe-Fe pairs with preserved structural features [Figure 12F]. Comparative experiments with a shorter Fe-Fe distance catalyst (Fe2/NC-S, ~0.25 nm) confirmed the critical role of interatomic spacing in catalytic enhancement [Figure 12G and H]. The Fe2/NC catalyst demonstrated outstanding ORR performance, with an E1/2 of 0.90 V (vs. RHE) and superior stability over 10,000 cycles [Figure 12I and J].

Heterogeneous dual-atom catalysts

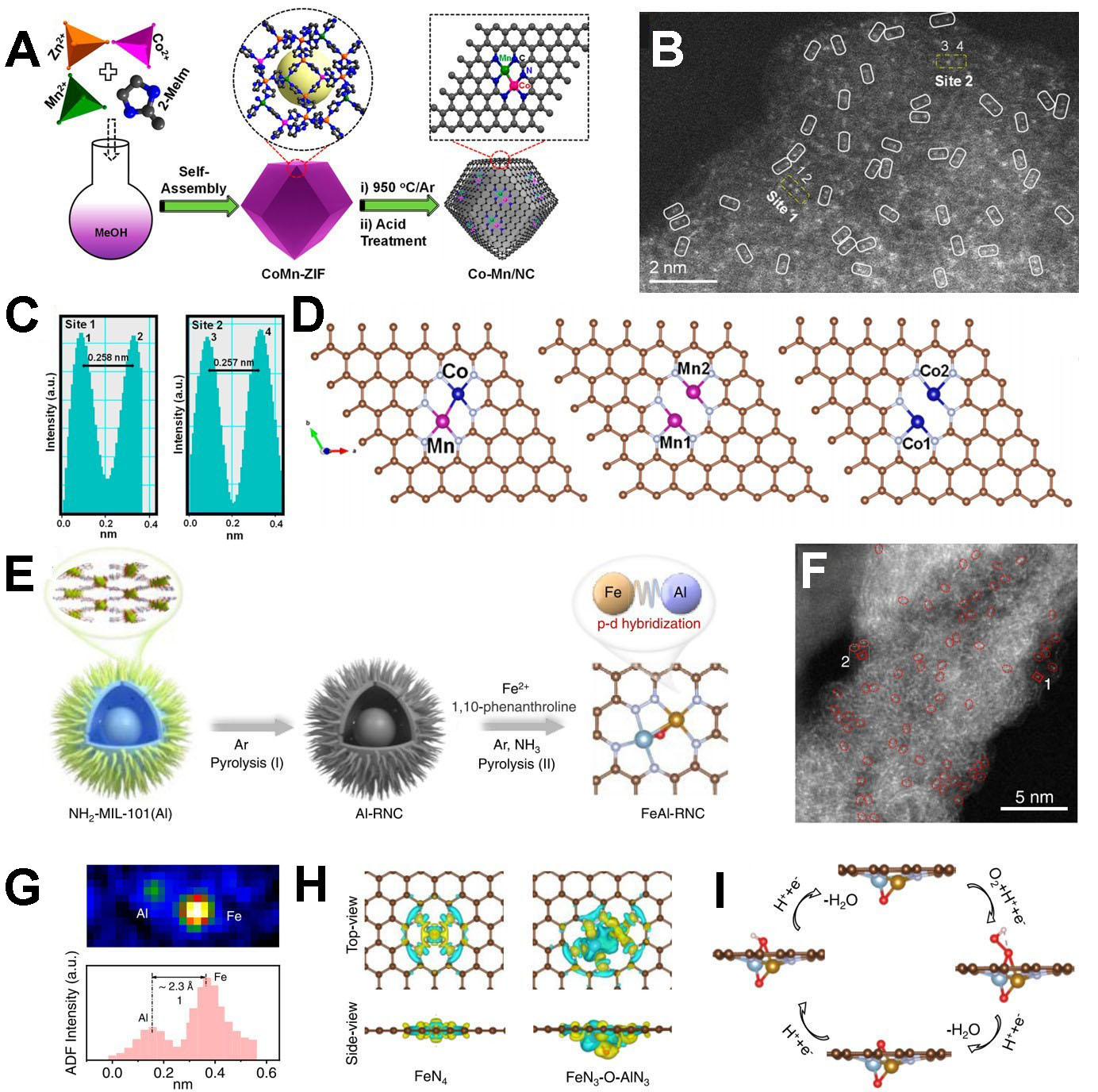

Similar to the synthesis of homologous dual-atom catalysts, heterogeneous dual-atom catalysts can be obtained by controlling the metal content and types in the MOF precursor, along with post-treatment conditions. As shown in Figure 13A, Dey et al. reported the synthesis of a dual single-atom catalyst featuring atomically isolated CoMn/NC, derived from Co/Mn-doped ZIF-8 via high-temperature calcination[160]. HAADF-STEM, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and synchrotron X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) analyses confirmed the atomic dispersion of

Figure 13. (A) Synthesis and (B) high-resolution HAADF-STEM image of the CoMn/NC catalyst; (C) intensity profiles obtained at sites 1 and 2 in (B); (D) optimized geometries of the CoN3-MnN3, MnN3-MnN3, and CoN3-CoN3 dual-atom catalyst models (A-D reproduced with permission from the American Chemical Society, copyright 2023)[160]; (E) Synthesis and (F) aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM image of the FeAl-RNC catalyst; (G) intensity profile and corresponding colored raster graphic of the Fe-Al atomic pairs; (H) differential charge densities of FeN4 and FeN3-O-AlN3 (top and side views); (I) schematic of the proposed ORR pathway of FeN3-O-AlN3 (E-I reproduced with permission from the American Chemical Society, copyright 2024)[131]. HAADF-STEM: High-angle annular dark

Additionally, Liu et al. developed FeAl-RNC with atomically dispersed Fe-Al dual-atom pairs

MOF-based cluster catalysts

Owing to their porous architectures, MOF materials can yield different types of metal catalysts depending on their intrinsic properties and the metal loading within their pore structures. By systematically tuning the metal content, SACs, dual-atom catalysts, or metal cluster catalysts can be obtained.

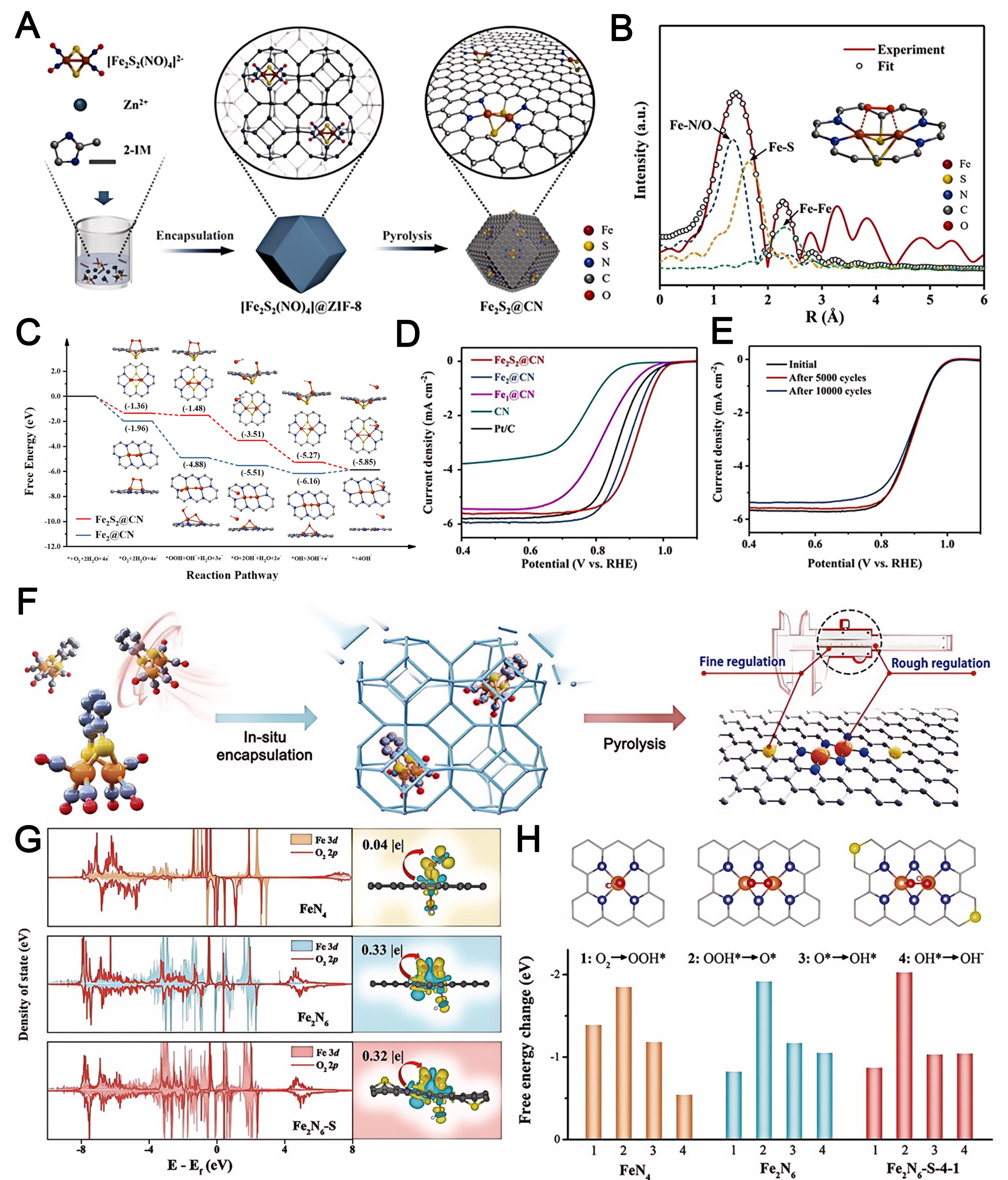

Based on ZIFs, Wang et al. developed non-planar, nest-like [Fe2S2] cluster catalysts exhibiting structural similarity to plant-type ferredoxin [Figure 14A][161]. Aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM measurements revealed numerous paired bright spots, confirming the successful synthesis of Fe2 clusters. EXAFS curve-fitting analysis [Figure 14B] further elucidated the fine structure of the Fe2S2 clusters. DFT calculations of the complete ORR reaction process indicated a notable difference in the adsorption mode of the second O atom when the first OH* was separated [Figure 14C]. This variation resulted in distinct deformations in the spatial structure of the active site, subsequently influencing its desorption behavior. Fe2S2@CN showed the highest relative E1/2 (0.92 V) among the tested catalysts and exhibited exceptional stability

Figure 14. (A) Synthetic procedure of non-planar nest-like [Fe2S2] cluster sites in the N-doped carbon plane; (B) corresponding

Liu et al. synthesized Fe2 clusters based on plant ferritin and encapsulated them within the cavities of ZIF-8 [Figure 14F][162]. These clusters featured a distinctive Fe2N6-S fine structure. The Fe 3d orbitals in Fe2N6 and Fe2N6-S exhibited pronounced orbital coupling [Figure 14G]. In FeN4, OH* intermediates strongly adsorbed to the Fe site, hindering desorption and electron transfer. This step was identified as the rate-determining step of the overall reaction, resulting in a higher overpotential (0.70 V). By contrast, Fe2N6-S displayed the lowest overpotential (0.37 V) among the three catalysts calculated [Figure 14H].

Others

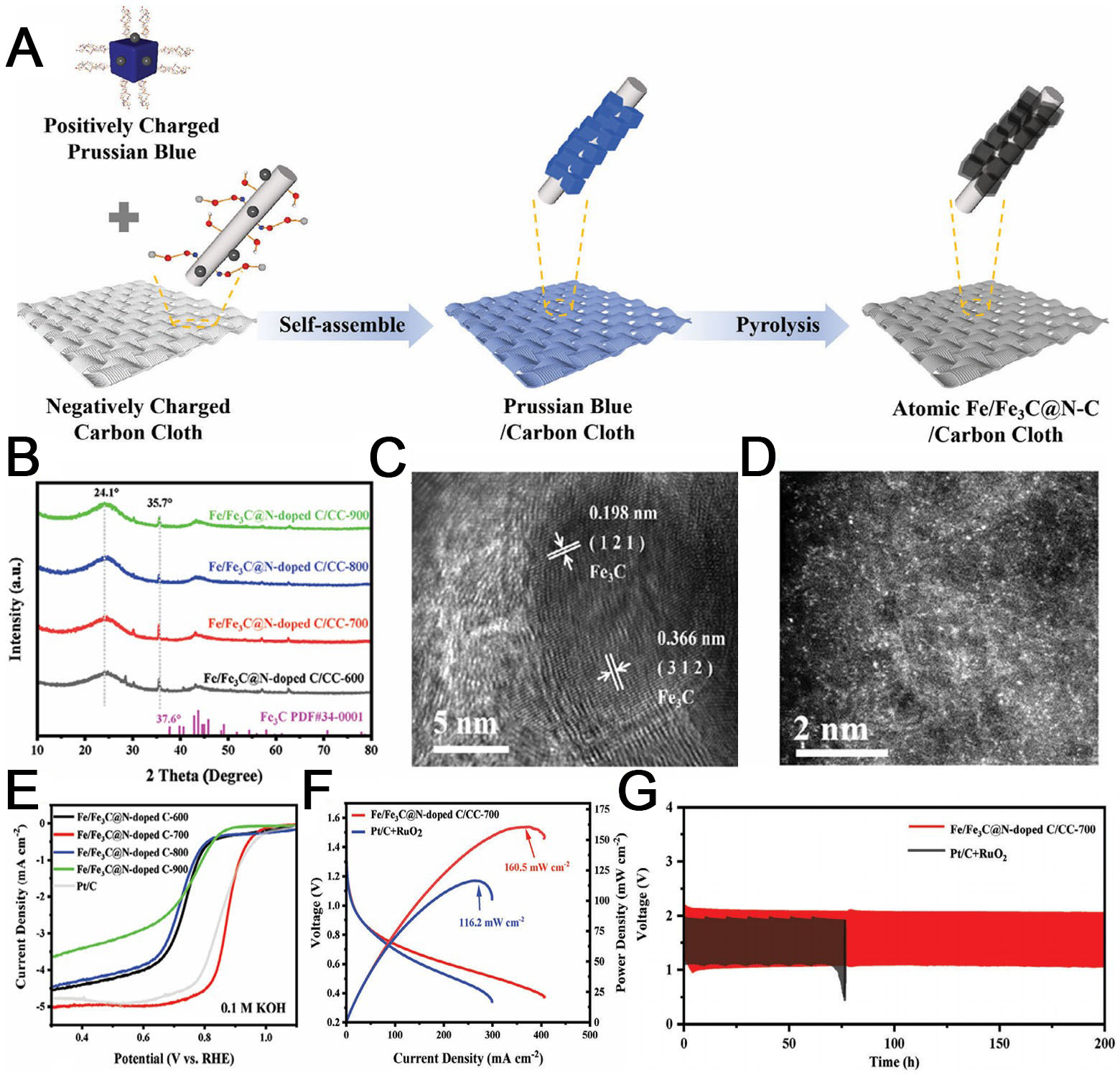

Several researchers have investigated the impacts of multiple catalytically active centers operating in concert on MOF substrates for ORR catalysis. For example, Wang et al. utilized Prussian blue as a self-assembly substrate on a carbon cloth [Figure 15A][163], synthesizing a catalyst Fe/Fe3C@N-C with both Fe3C and atomically dispersed Fe-N4 active sites following calcination. All catalysts presented the peaks of Fe3C in their X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns [Figure 15B] and the (121) and (312) crystal planes of Fe3C in their TEM images, confirming the formation of Fe3C [Figure 15C]. Concurrently, a substantial quantity of iron single atoms (Fe-N4 active sites) were identified in the HAADF-STEM images [Figure 15D]. The electron microscopy observations were corroborated by the EXAFS results. As the Fe/Fe3C@N-doped C-700 catalyst performed excellently in RDE testing (E1/2 = 0.903 V), it was installed as the cathode in a ZAB. The Fe/Fe3C@N-doped C-700 achieved a higher power density and higher stability than various commercial precious metal catalysts, demonstrating its considerable application potential [Figure 15E-G].

Figure 15. (A) Synthesis of the Fe/Fe3C@N-C catalyst; (B) XRD patterns of the as-prepared samples; (C) TEM and (D) HAADF-STEM images of Fe/Fe3C@N-C; (E) LSV curves of Fe/Fe3C@N-C in O2-saturated 0.1 KOH; (F) discharge polarization curves and power density curves; (G) Galvanostatic cycling stability of the as-prepared samples under 10 mA cm-2 charge and discharge conditions (A-G reproduced with permission from Wiley-VCH, copyright 2024)[163]. HAADF-STEM: High-angle annular dark field-scanning transmission electron microscopy; XRD: X-ray diffraction.

IN SITU DETECTION OF MOF-DERIVED CATALYSTS

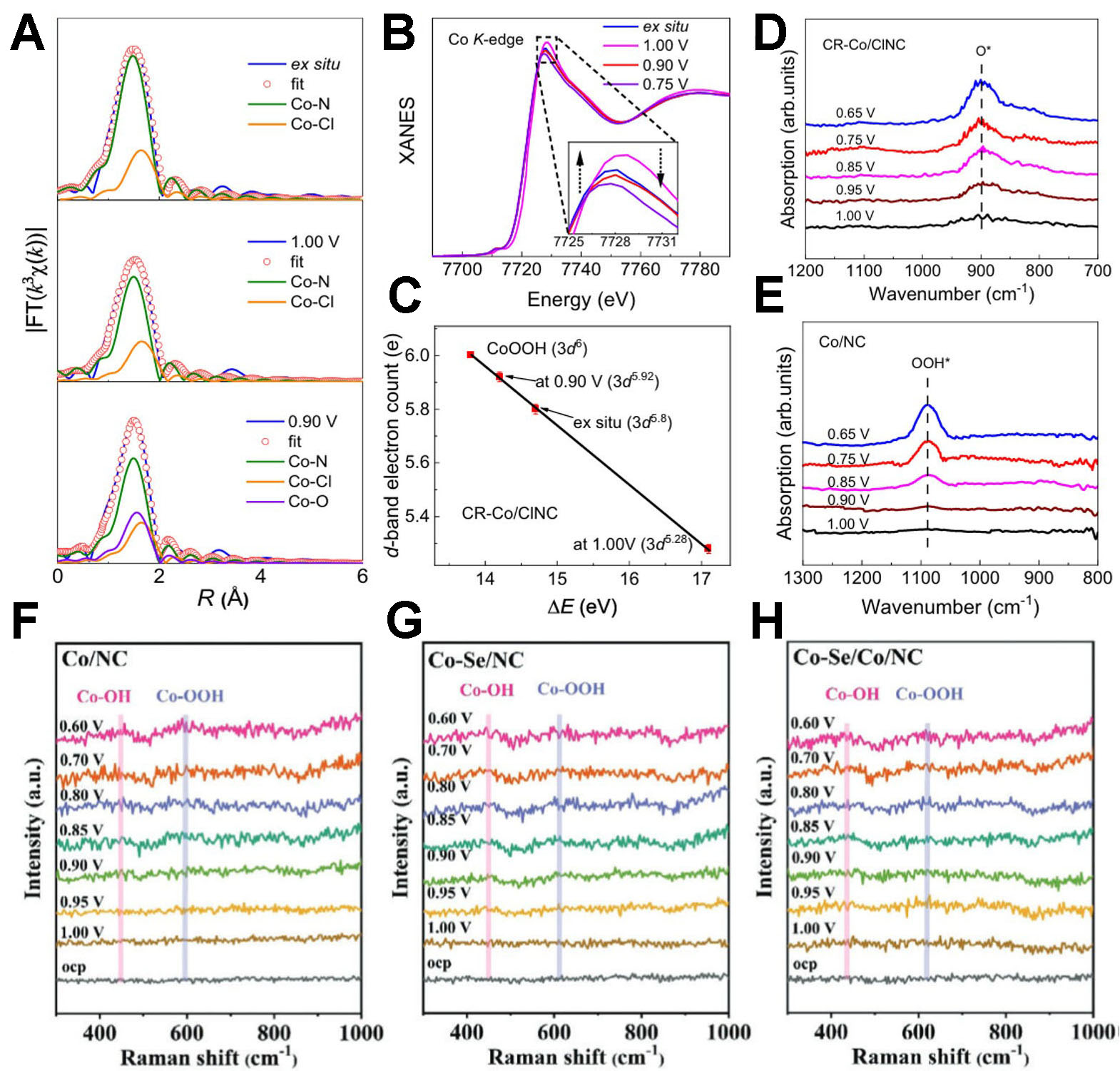

In situ monitoring methods, which capture real-time or quasi-real-time information under actual reaction conditions, have revolutionized ORR research. By overcoming the limitations of traditional non-in situ characterization, they enable direct observation of the reaction mechanism, kinetic processes, catalyst structural evolution, and failure mechanisms in ORR[164,165]. For instance, Liu et al. used in situ XAFS and in situ synchrotron radiation infrared spectroscopy (SRIR) to monitor changes in CR-Co/ClNC catalysts during the ORR[166]. In situ EXAFS and X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) results indicated that during the early reaction stage, the d-band electrons underwent rapid modulation as the fractured Cl-Co-N4 moieties evolved into coordination-reduced Cl-Co-N2 species [Figure 16A-C]. SRIR spectra during ORR showed only the absorption band of *O, indicating rapid cleavage of the O-O bond in *O and the dynamic evolution of OH intermediates on Cl-Co-N2 sites [Figure 16D and E].

Figure 16. (A) Curve-fitting analysis of the EXAFS spectra of CR-Co/ClNC, (B) XANES spectra of the Co K-edge of CR-Co/ClNC recorded at different applied potentials during the ORR process; (C) fitted average formal d-band electron counts of Co in CR-Co/ClNC under ex situ, 1.00 V, and 0.90 V conditions, determined from the absorption edges of the Co K-edge XANES spectra. In situ synchrotron radiation infrared spectra of (D) CR-Co/ClNC and (E) Co/NC under various potentials (A-E reproduced with permission from Springer Nature, copyright 2024)[166]. In situ Raman spectra of (F) Co/NC, (G) Co-Se/NC, and (H) Co-Se/Co/NC in 0.1 M KOH (F-H reproduced with permission from Wiley-VCH, copyright 2024)[167]. EXAFS: Extended X-ray absorption fine structure; ORR: oxygen reduction reaction; XANES: X-ray absorption near-edge structure.

Similarly, Hu et al. employed in situ Raman spectroscopy to track structural changes in catalysts during ORR[167]. Upon application of voltage, two peaks appeared in the Raman spectrum at 457 and 628 cm-1, corresponding to Co-OH and Co-OOH, respectively. Among the catalysts studied, CoSe/Co/NC exhibited the fastest reaction rate, consistent with its outstanding ORR performance [Figure 16F-H].

Overall, these in situ characterization results provide detailed insights into catalyst transformations during ORR, deepening understanding of the reaction process and offering new concepts and approaches for designing advanced catalysts.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

In conclusion, the ORR stands as a cornerstone of clean energy conversion, and unlocking its full potential hinges on advancing high-performance catalysts to overcome its intrinsically sluggish kinetics. MOFs have emerged as versatile precursors and templates for the fabrication of atomically precise ORR catalysts: via pyrolysis or solvothermal synthesis, these materials retain the structural tunability of MOFs while enabling atomic-level control over catalyst composition and coordination environments, thereby delivering substantial improvements in ORR activity.

As described earlier, the rational selection of ligands-including porphyrins, imidazoles, and carboxylates-coupled with precise modulation of metal loading and species, yields a diverse array of active center architectures, spanning single-atom, dual-atom, and cluster configurations. This approach not only delineates the pivotal role of ligands in governing catalyst evolution but also elucidates the intricate interplay between coordination environment, active center geometry, intermediate adsorption, and ORR performance.

Notwithstanding these advances, critical challenges persist, notably the real-time monitoring of MOF pyrolysis dynamics and the in-situ characterization of metal coordination evolution under operational catalytic conditions. Looking ahead, the integration of cutting-edge in-situ characterization with first-principles calculations will deepen our mechanistic understanding of structure-activity relationships, while translating MOFs-derived ORR catalysts into practical devices such as zinc-air batteries and fuel cells will be instrumental in driving their commercial deployment. These efforts will not only underpin the transition to a low-carbon energy landscape but also provide a robust technical framework for addressing global energy challenges.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Literature search and organization and manuscript drafting: Xu, D.; Jiang, J.

Administrative and software technical support: Liu, D.; Dou, Y.

Manuscript revision: Duan, J.; Zhuang, Z.

Supervision and suggestion: Wei, X.; Yang, J.

Project supervision: Liu, X.; Wang, D.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the NSFC National Natural Science Foundation of China (22101029, 22471235, 52201261), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (2222006) and Beijing Municipal Financial Project BJAST Young Scholar Programs B (YS202202), and the Financial Program of BJAST (25CA002, 25CA011-02).

Conflicts of interest

Wang, D. is an Associate Editor of the journal Microstructures. Wang, D. was not involved in any steps of editorial processing, notably including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or decision making. The other authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Nie, Y.; Li, L.; Wei, Z. Recent advancements in Pt and Pt-free catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 2168-201.

2. Seh, Z. W.; Kibsgaard, J.; Dickens, C. F.; Chorkendorff, I.; Nørskov, J. K.; Jaramillo, T. F. Combining theory and experiment in electrocatalysis: insights into materials design. Science 2017, 355, eaad4998.

3. Fei, H.; Dong, J.; Feng, Y.; et al. General synthesis and definitive structural identification of MN4C4 single-atom catalysts with tunable electrocatalytic activities. Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 63-72.

4. Wang, H.; Xu, S.; Tsai, C.; et al. Direct and continuous strain control of catalysts with tunable battery electrode materials. Science 2016, 354, 1031-6.

5. Shao, M.; Chang, Q.; Dodelet, J. P.; Chenitz, R. Recent advances in electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3594-657.

6. Cui, H.; Liu, T.; Chen, Y.; et al. Dynamics of non-metal-regulated FeCo bimetal microenvironment on oxygen reduction reaction activity and intrinsic mechanism. Nano. Res. 2023, 16, 2199-208.

7. Zhang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L.; et al. Bead-like cobalt-nitrogen co-doped carbon nanocage/carbon nanofiber composite: a high-performance oxygen reduction electrocatalyst for zinc-air batteries. Nano. Res. 2023, 16, 545-54.

8. Huang, Z.; Zhan, C.; Yuan, Y.; et al. Designing natural cell-inspired heme-spurred membrane electrode assembly for fuel cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 22818-26.

9. Chung, H. T.; Cullen, D. A.; Higgins, D.; et al. Direct atomic-level insight into the active sites of a high-performance PGM-free ORR catalyst. Science 2017, 357, 479-84.

10. Chen, C.; Kang, Y.; Huo, Z.; et al. Highly crystalline multimetallic nanoframes with three-dimensional electrocatalytic surfaces. Science 2014, 343, 1339-43.

11. Li, M.; Zhao, Z.; Cheng, T.; et al. Ultrafine jagged platinum nanowires enable ultrahigh mass activity for the oxygen reduction reaction. Science 2016, 354, 1414-9.

12. Liu, G.; Shih, A. J.; Deng, H.; et al. Site-specific reactivity of stepped Pt surfaces driven by stress release. Nature 2024, 626, 1005-10.

13. Ji, N.; Sheng, H.; Liu, S.; et al. Boosting oxygen reduction in acidic media through integration of Pt-Co alloy effect and strong interaction with carbon defects. Nano. Res. 2024, 17, 7900-8.

14. Zhang, H.; Sun, Q.; He, Q.; et al. Single Cu atom dispersed on S,N-codoped nanocarbon derived from shrimp shells for highly-efficient oxygen reduction reaction. Nano. Res. 2022, 15, 5995-6000.

15. Hu, Y.; Zhu, M.; Luo, X.; et al. Coplanar Pt/C nanomeshes with ultrastable oxygen reduction performance in fuel cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 6533-8.

16. Li, Q.; Zhang, D.; Wu, J.; et al. Cation-deficient perovskites greatly enhance the electrocatalytic activity for oxygen reduction reaction. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2309266.

17. Jiao, L.; Li, J.; Richard, L. L.; et al. Chemical vapour deposition of Fe-N-C oxygen reduction catalysts with full utilization of dense Fe-N4 sites. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 1385-91.

18. Liu, S.; Li, C.; Zachman, M. J.; et al. Atomically dispersed iron sites with a nitrogen-carbon coating as highly active and durable oxygen reduction catalysts for fuel cells. Nat. Energy. 2022, 7, 652-63.

19. Stamenkovic, V. R.; Fowler, B.; Mun, B. S.; et al. Improved oxygen reduction activity on Pt3Ni(111) via increased surface site availability. Science 2007, 315, 493-7.

20. Yuan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Luo, D.; et al. Recent progress on mechanisms, principles, and strategies for high-activity and high-stability non-PGM fuel cell catalyst design. Carbon. Energy. 2024, 6, e426.

21. Chen, M. Strong metal-support interaction of Pt-based electrocatalysts with transition metal oxides/nitrides/carbides for oxygen reduction reaction. Microstructures 2023, 3, 2023025.

22. Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Qu, Y.; et al. Review of metal catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction: from nanoscale engineering to atomic design. Chem 2019, 5, 1486-511.

23. Tang, B.; Zhou, Y.; Ji, Q.; et al. A Janus dual-atom catalyst for electrocatalytic oxygen reduction and evolution. Nat. Synth. 2024, 3, 878-90.

24. Ahmad, M.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; et al. Metal-organic framework-based single-atom electro-/photocatalysts: synthesis, energy applications, and opportunities. Carbon. Energy. 2024, 6, e382.

25. Kitagawa, S.; Kitaura, R.; Noro, S. Functional porous coordination polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 2334-75.

26. Lee, J.; Farha, O. K.; Roberts, J.; Scheidt, K. A.; Nguyen, S. T.; Hupp, J. T. Metal-organic framework materials as catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1450-9.

27. Gao, Y.; Yang, C.; Sun, F.; et al. Ligand-Tuning metallic sites in molecular complexes for efficient water oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202415755.

28. Sui, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; et al. Silver based single atom catalyst with heteroatom coordination environment as high performance oxygen reduction reaction catalyst. Nano. Res. 2022, 15, 7968-75.

29. Liu, S.; Liu, M.; Li, X.; et al. Metal organic polymers with dual catalytic sites for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution reactions. Carbon. Energy. 2023, 5, e303.

30. Wu, J.; Zhu, X.; Li, Q.; et al. Enhancing radiation-resistance and peroxidase-like activity of single-atom copper nanozyme via local coordination manipulation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6174.

31. Yang, B.; Li, B.; Xiang, Z. Advanced MOF-based electrode materials for supercapacitors and electrocatalytic oxygen reduction. Nano. Res. 2023, 16, 1338-61.

32. Liang, C.; Zhang, T.; Sun, S.; et al. Yolk-shell FeCu/NC electrocatalyst boosting high-performance zinc-air battery. Nano. Res. 2024, 17, 7918-25.

33. Cheng, K.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, D.; Song, M.; Wang, Y. Jellyfish bio-inspired Fe@CNT@CuNC derived from ZIF-8 for cathodic oxygen reduction. Nano. Res. 2024, 17, 2352-9.

34. Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Cai, S.; Wu, J. Recent advances in hierarchical porous engineering of MOFs and their derived materials for catalytic and battery: methods and application. Small 2024, 20, 2303473.

35. Wen, S.; Yan, L.; Zhao, X. Synergistic effect of structural and interfacial engineering of metal-organic framework-derived superstructures for energy and environmental applications. Adv. Energy. Mater. , 2025, 2502432.

36. Xu, H.; Geng, P.; Feng, W.; Du, M.; Kang, D. J.; Pang, H. Recent advances in metal-organic frameworks for electrochemical performance of batteries. Nano. Res. 2024, 17, 3472-92.

37. Wang, X.; Zhang, G.; Yin, W.; et al. Metal-organic framework-derived phosphide nanomaterials for electrochemical applications. Carbon. Energy. 2022, 4, 246-81.

38. Liu, J.; Chen, L.; Cui, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Su, C. Y. Applications of metal-organic frameworks in heterogeneous supramolecular catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6011-61.

39. Bai, J.; Lian, Y.; Deng, Y.; et al. Simultaneous integration of Fe clusters and NiFe dual single atoms in nitrogen-doped carbon for oxygen reduction reaction. Nano. Res. 2024, 17, 2291-7.

40. Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zeng, Y.; et al. Host-guest engineering of dual-metal nitrogen carbides as bifunctional oxygen electrocatalysts for long-cycle rechargeable Zn-air battery. Carbon. Energy. 2025, 7, e682.

41. Xia, B. Y.; Yan, Y.; Li, N.; Wu, H. B.; Lou, X. W.; Wang, X. A metal-organic framework-derived bifunctional oxygen electrocatalyst. Nat. Energy. 2016, 1, 15006.

42. Yin, P.; Yao, T.; Wu, Y.; et al. Single cobalt atoms with precise N-coordination as superior oxygen reduction reaction catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 10800-5.

43. Zhang, L.; Meng, Q.; Zheng, R.; et al. Microenvironment regulation of M-N-C single-atom catalysts towards oxygen reduction reaction. Nano. Res. 2023, 16, 4468-87.

44. Zhou, T.; Guan, Y.; He, C.; et al. Building Fe atom-cluster composite sites using a site occupation strategy to boost electrochemical oxygen reduction. Carbon. Energy. 2024, 6, e477.

45. Guo, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wu, Y. Multiscale designing principle of M-N-C towards high performance PEMFC. Microstructures 2025, 5, 2025031.

46. Cheng, W.; Zhao, X.; Su, H.; et al. Lattice-strained metal-organic-framework arrays for bifunctional oxygen electrocatalysis. Nat. Energy. 2019, 4, 115-22.

47. Xiong, Y.; Yang, Y.; DiSalvo, F. J.; Abruña, H. D. Metal-organic-framework-derived Co-Fe bimetallic oxygen reduction electrocatalysts for alkaline fuel cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 10744-50.

48. Ma, R.; Li, Q.; Yan, J.; et al. Thermodynamically controllable synthesis of ZIF-8 exposing different facets and their applications in single atom catalytic oxygen reduction reactions. Nano. Res. 2023, 16, 9618-24.

49. Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; et al. Beads-on-string hierarchical structured electrocatalysts for efficient oxygen reduction reaction. Carbon. Energy. 2023, 5, e253.

50. Jiao, L.; Wan, G.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, H.; Yu, S. H.; Jiang, H. L. From metal-organic frameworks to single-atom Fe implanted N-doped porous carbons: efficient oxygen reduction in both alkaline and acidic media. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 8525-9.

51. Zhuang, Z.; Huang, A.; Tan, X.; et al. p-Block-metal bismuth-based electrocatalysts featuring tunable selectivity for high-performance oxygen reduction reaction. Joule 2023, 7, 1003-15.

52. Chen, H.; Zhang, H.; Chi, K.; Zhao, Y. Pyrimidine-containing covalent organic frameworks for efficient photosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide via one-step two electron oxygen reduction process. Nano. Res. 2024, 17, 9498-506.

53. Luo, E.; Chu, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Pyrolyzed M-Nx catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction: progress and prospects. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 2158-85.

54. Zhu, X.; Shao, Y.; Xia, D.; et al. When graphitic nitrogen meets pentagons: selective construction and spectroscopic evidence for improved four-electron oxygen reduction electrocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2414976.

56. Nørskov, J. K.; Rossmeisl, J.; Logadottir, A.; et al. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004, 108, 17886-92.

57. Huang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Cao, L.; et al. High-performance transition metal-doped Pt3Ni octahedra for oxygen reduction reaction. Science 2015, 348, 1230-4.

58. Islam, M. N.; Mansoor Basha, A. B.; Kollath, V. O.; Soleymani, A. P.; Jankovic, J.; Karan, K. Designing fuel cell catalyst support for superior catalytic activity and low mass-transport resistance. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6157.

59. Hu, Y.; Han, X.; Hu, S.; et al. Surface-diffusion-induced amorphization of Pt nanoparticles over Ru oxide boost acidic oxygen evolution. Nano. Lett. 2024, 24, 5324-31.

60. Adabi, H.; Shakouri, A.; Ul Hassan, N.; et al. High-performing commercial Fe-N-C cathode electrocatalyst for anion-exchange membrane fuel cells. Nat. Energy. 2021, 6, 834-43.

61. Mu, X. Q.; Liu, S. L.; Zhang, M. Y.; et al. Symmetry-broken ru nanoparticles with parasitic Ru-Co dual-single atoms overcome the volmer step of alkaline hydrogen oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202319618.

62. Guan, S.; Yuan, Z.; Zhao, S.; et al. Efficient hydrogen generation from ammonia borane hydrolysis on a tandem ruthenium-platinum-titanium catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202408193.

63. Li, Y.; Niu, S.; Liu, P.; et al. Ruthenium nanoclusters and single atoms on α-MoC/N-doped carbon achieves low-input/input-free hydrogen evolution via decoupled/coupled hydrazine oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202316755.

64. Hu, Y.; Chao, T.; Li, Y.; et al. Cooperative Ni(Co)-Ru-P sites activate dehydrogenation for hydrazine oxidation assisting self-powered H2 production. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202308800.

65. Chao, T.; Xie, W.; Hu, Y.; et al. Reversible hydrogen spillover at the atomic interface for efficient alkaline hydrogen evolution. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 1397-406.

66. Lien, H. T.; Chang, S. T.; Chen, P. T.; et al. Probing the active site in single-atom oxygen reduction catalysts via operando X-ray and electrochemical spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4233.

67. Wang, Q.; Kaushik, S.; Xiao, X.; Xu, Q. Sustainable zinc-air battery chemistry: advances, challenges and prospects. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 6139-90.

68. Shao, W.; Yan, R.; Zhou, M.; et al. Carbon-based electrodes for advanced zinc-air batteries: oxygen-catalytic site regulation and nanostructure design. Electrochem. Energy. Rev. 2023, 6, 11.

69. Zou, Y.; Su, Y.; Yu, Y.; et al. On the role of Zn and Fe doping in nitrogen-carbon electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction. Nano. Res. 2024, 17, 9564-72.

70. Pang, M.; Yang, M.; Zhang, H.; et al. Synthesis techniques, mechanism, and prospects of high-loading single-atom catalysts for oxygen reduction reactions. Nano. Res. 2024, 17, 9371-96.

71. Mun, Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, K.; et al. Versatile strategy for tuning ORR activity of a single Fe-N4 site by controlling electron-withdrawing/donating properties of a carbon plane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 6254-62.

72. Cao, S.; Sun, T.; Li, J.; Li, Q.; Hou, C.; Sun, Q. The cathode catalysts of hydrogen fuel cell: from laboratory toward practical application. Nano. Res. 2023, 16, 4365-80.

73. Jiao, K.; Xuan, J.; Du, Q.; et al. Designing the next generation of proton-exchange membrane fuel cells. Nature 2021, 595, 361-9.

74. Bing, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Ghosh, D.; Zhang, J. Nanostructured Pt-alloy electrocatalysts for PEM fuel cell oxygen reduction reaction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 2184-202.

75. Chao, T.; Luo, X.; Zhu, M.; et al. The promoting effect of interstitial hydrogen on the oxygen reduction performance of PtPd alloy nanotubes for fuel cells. Nano. Res. 2023, 16, 2366-72.

76. Yu, H.; Li, C.; Lei, Y.; Xiang, Z. Strategic secondary coordination implantation towards efficient and stable Fe-N-C electrocatalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction in PEMFCs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202508141.

77. Tang, B.; Ji, Q.; Zhang, X.; et al. Symmetry breaking of FeN4 Moiety via edge defects for acidic oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202424135.

78. Chen, N.; Lee, Y. M. Anion exchange polyelectrolytes for membranes and ionomers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2021, 113, 101345.

79. Zeng, R.; Li, H.; Shi, Z.; et al. Origins of enhanced oxygen reduction activity of transition metal nitrides. Nat. Mater. 2024, 23, 1695-703.

80. Sun, K.; Dong, J.; Sun, H.; et al. Co(CN)3 catalysts with well-defined coordination structure for the oxygen reduction reaction. Nat. Catal. 2023, 6, 1164-73.

81. Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, S.; et al. Alkoxy side chain engineering in metal-free covalent organic frameworks for efficient oxygen reduction. Adv. Mater. 2025, 2501603.

82. Wu, R.; Zuo, J.; Fu, C.; et al. Enhancing rechargeable zinc-air batteries with atomically dispersed zinc iron cobalt planar sites on porous nitrogen-doped carbon. ACS. Nano. 2025, 19, 20215-24.

83. Guo, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, N.; et al. Advanced design strategies for Fe-based metal-organic framework-derived electrocatalysts toward high-performance Zn-air batteries. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 1725-55.

84. Zhang, H.; Meng, Y.; Zhong, H.; et al. Bulk preparation of free-standing single-iron-atom catalysts directly as the air electrodes for high-performance zinc-air batteries. Carbon. Energy. 2023, 5, e289.

85. Sun, C.; Liu, Y.; Lv, Z.; et al. Coordination-environment regulation of atomic Co-Mn dual-sites for efficient oxygen reduction reaction. Nano. Res. 2024, 17, 6841-8.

86. Li, J.; Lu, T.; Fang, Y.; et al. The manipulation of rectifying contact of Co and nitrogen-doped carbon hierarchical superstructures toward high-performance oxygen reduction reaction. Carbon. Energy. 2024, 6, e529.

87. Man, H.; Chen, G.; Wang, F.; et al. Entropy engineering activates Cu-Fe inertia center from prussian blue analogs with micro-strains for oxygen electrocatalysis in Zn-air batteries. Carbon. Energy. 2025, 7, e693.

88. Cui, K.; Tang, X.; Xu, X.; Kou, M.; Lyu, P.; Xu, Y. Crystalline dual-porous covalent triazine frameworks as a new platform for efficient electrocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202317664.

89. Zhang, B.; Dang, J.; Li, H.; et al. Orderly stacked “Tile” architecture with single-atom iron boosts oxygen reduction in liquid and solid-state Zn-air batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. , 2025, 2502834.

90. Wang, Y.; Yang, T.; Fan, X.; et al. Anchoring Fe species on the highly curved surface of S and N Co-doped carbonaceous nanosprings for oxygen electrocatalysis and a flexible zinc-air battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202313034.

91. Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Mu, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, D.; Dai, Z. Atomically dispersed multi-site catalysts: bifunctional oxygen electrocatalysts boost flexible zinc-air battery performance. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 4847-70.

92. Khan, I. A.; Qian, Y.; Badshah, A.; Nadeem, M. A.; Zhao, D. Highly porous carbon derived from MOF-5 as a support of ORR electrocatalysts for fuel cells. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2016, 8, 17268-75.

93. Zhao, S.; Yin, H.; Du, L.; et al. Carbonized nanoscale metal-organic frameworks as high performance electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction reaction. ACS. Nano. 2014, 8, 12660-8.

94. Chen, Y.; Kang, H.; Cheng, M.; et al. Single-atom catalysts originated from metal-organic frameworks for sulfate radical-based advanced oxidation processes: critical insights into mechanisms. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2309223.

95. Chai, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; et al. Cube-shaped metal-nitrogen-carbon derived from metal-ammonia complex-impregnated metal-organic framework for highly efficient oxygen reduction reaction. Carbon 2020, 158, 719-27.

96. Zhang, S.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; et al. Multiple active cobalt species embedded in microporous nitrogen-doped carbon network for the selective production of hydrogen peroxide. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2023, 631, 101-13.

97. Yang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Xue, J.; et al. MOF-derived N-doped carbon nanosticks coupled with Fe phthalocyanines for efficient oxygen reduction. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 464, 142668.

98. Chai, L.; Song, J.; Kumar, A.; et al. Bimetallic-MOF derived carbon with single Pt anchored C4 atomic group constructing super fuel cell with ultrahigh power density and self-change ability. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2308989.

99. Du, M.; Chu, B.; Wang, Q.; et al. Dual Fe/I single-atom electrocatalyst for high-performance oxygen reduction and wide-temperature quasi-solid-state Zn-air batteries. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2412978.

100. Liu, D.; Srinivas, K.; Ma, F.; et al. Fe species anchored N, S-doped carbon as nonprecious catalyst for boosting oxygen reduction reaction. J. Alloys. Compd. 2023, 937, 168496.

101. Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, T.; et al. Rational design of porous Fex-N@MOF as a highly efficient catalyst for oxygen reduction over a wide pH range. J. Alloys. Compd. 2023, 944, 169039.

102. Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Yang, X.; et al. Modulator directed synthesis of size-tunable mesoporous MOFs and their derived nanocarbon-based electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 486, 150088.

103. Liang, Z.; Zhou, G.; Tan, H.; et al. Constructing Co4(SO4)4 clusters within metal-organic frameworks for efficient oxygen electrocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2408094.

104. Li, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, W.; Duan, J.; Jin, W. Ultrathin 2D catalysts with N-coordinated single Co atom outside Co cluster for highly efficient Zn-air battery. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 421, 129719.

105. Rong, J.; Chen, W.; Gao, E.; et al. Design of atomically dispersed CoN4 sites and Co clusters for synergistically enhanced oxygen reduction electrocatalysis. Small 2024, 20, 2402323.

106. Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, M.; et al. Catalysts by pyrolysis: Transforming metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) precursors into metal-nitrogen-carbon (M-N-C) materials. Mater. Today. 2023, 69, 66-78.

107. Zitolo, A.; Goellner, V.; Armel, V.; et al. Identification of catalytic sites for oxygen reduction in iron-and nitrogen-doped graphene materials. Nature. Mater. 2015, 14, 937-42.

108. Arafat, Y.; Azhar, M. R.; Zhong, Y.; Abid, H. R.; Tadé, M. O.; Shao, Z. Advances in zeolite imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs) derived bifunctional oxygen electrocatalysts and their application in zinc-air batteries. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2021, 11, 2100514.

109. Nguyen, Q. H.; Tinh, V. D. C.; Oh, S.; et al. Metal-organic framework-polymer complex-derived single-atomic oxygen reduction catalyst for anion exchange membrane fuel cells. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 481, 148508.

110. Yang, Y.; Lou, J.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Ice-templating co-assembly of dual-MOF superstructures derived 2D carbon nanobelts as efficient electrocatalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477, 146900.