Application of senescence reporter mouse models in panvascular diseases

Abstract

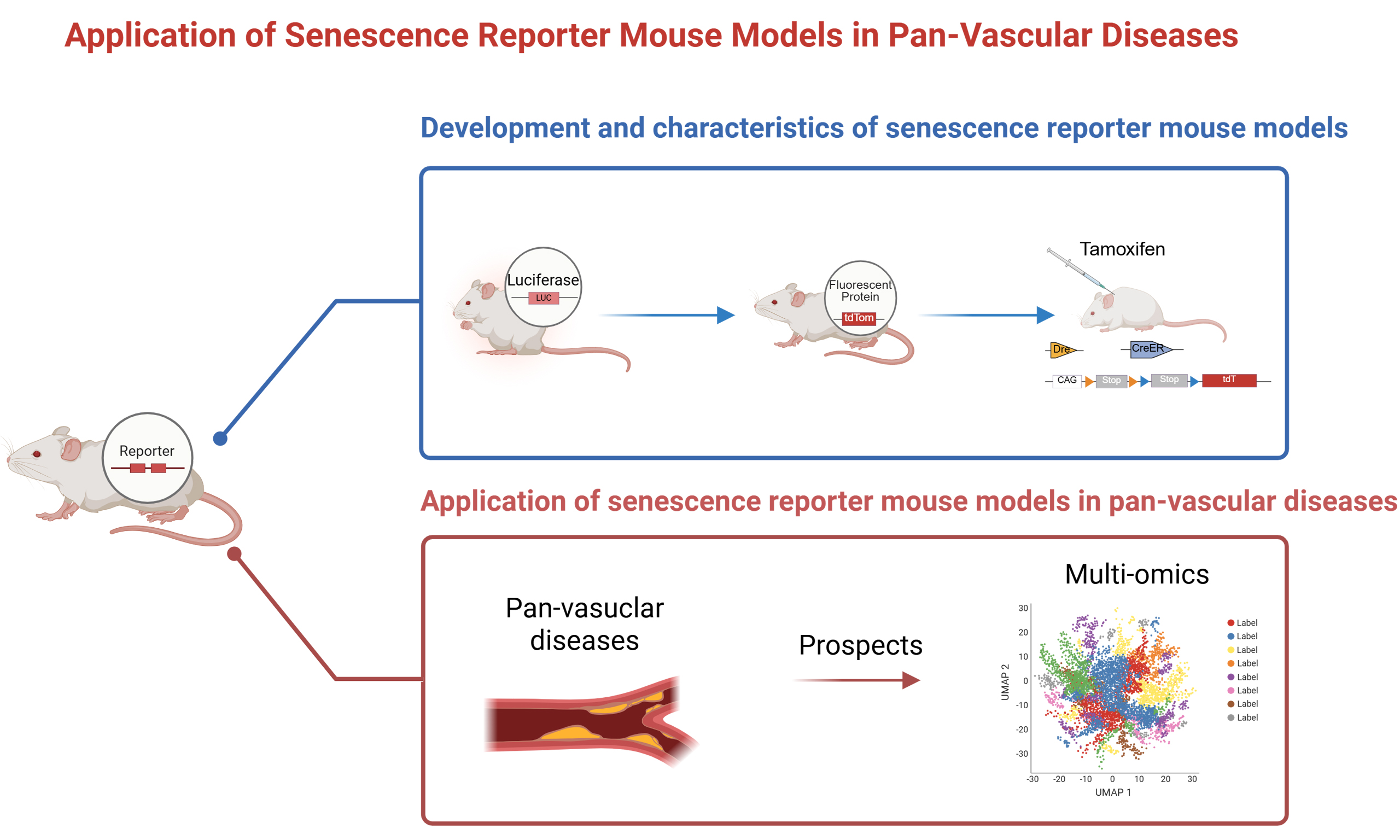

Vascular ageing accelerates panvascular diseases such as atherosclerosis, age-related arterial stiffening, pulmonary hypertension and cerebral microvascular dysfunction, yet the causal roles of senescent cells remain uncertain. This review aims to clarify those roles by systematically mapping the technological evolution, functional features and disease-specific applications of senescence reporter mouse models. We categorize senescence reporter mouse models into senescence tracing models and senescence eliminating models, and track three successive generations that progressively increased temporal, spatial and functional specificity. First-generation luciferase lines enabled

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Panvascular disease refers to a group of systemic vascular disorders characterized by atherosclerosis as a common pathological basis, involving large, medium, and micro-vessels and affecting vital organs such as the heart, brain, kidneys, limbs, and aorta. Representative conditions include coronary artery disease, ischemic stroke, peripheral artery disease, aortic aneurysm or dissection, and pulmonary hypertension (PH)[1]. With the acceleration of global population aging, the incidence and mortality rates of panvascular diseases continue to rise, becoming a significant threat to human health. As vascular aging is recognized as a critical component that accelerates panvascular disease progression[2,3], a deeper understanding of its mechanisms is essential for the prevention and treatment of panvascular diseases.

Vascular aging is a complex biological process involving multiple cell types and signaling pathways, with cellular senescence at its core. Cellular senescence is a stable and irreversible cell cycle arrest induced by factors such as DNA damage, oxidative stress, telomere attrition, and chronic inflammation[4]. Senescent cells also secrete various inflammatory cytokines, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and growth factors, collectively termed the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)[5]. Consequently, several biomarkers, including cell cycle inhibitors [cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A, CDKN2A (p16Ink4a) or cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A, CDKN1A (p21Waf1/Cip1)], senescence-associated β-galactosidase

Although these senescence markers have illuminated essential features of ageing, they fall short of accurately reflecting the complex microenvironment of vascular tissues in vivo. Moreover, the causal relationship between senescent cells and panvascular diseases, whether senescent cells drive pathology or result from disease progression, has remained a longstanding challenge. Consequently, senescence reporter mouse models have emerged, combining senescence marker promoters with various functional elements, enabling real-time and dynamic quantitative detection of senescent cells in vivo and providing excellent tools for studying cellular senescence in panvascular diseases.

Senescence reporter mouse technologies are categorized based on their functional characteristics into tracing mouse models and eliminating mouse models. To our knowledge, both categories have undergone three generations of technological evolution, continuously enhancing temporal and spatial specificity, and finally functional specificity aimed at monitoring and manipulating biological processes. This evolution reflects the integration of precision medicine concepts into senescence research, shifting from simple marker detection to systematic analyses of complex biological processes and laying the foundation for studying senescence mechanisms and therapeutic strategies.

Senescence reporter mouse models have demonstrated significant value in studying vascular aging across diverse disease contexts, ranging from atherosclerosis, aortic disease, pulmonary arterial disease to cerebrovascular dysfunction. However, systematic comparative analyses of their technical features, applicable scopes, and limitations remain lacking. To address this gap, we summarize the development of senescence reporter mouse models, highlight their applications in panvascular disease research, and discuss their advantages and limitations, providing perspectives for future advances in vascular aging studies.

FUNCTIONAL AND MOLECULAR CHARACTERISTICS OF VASCULAR AGING

Vascular aging refers to the age-related remodeling of vascular structure and function. Structural remodeling of aging vessels is characterized by increased vessel wall thickness, decreased elasticity, and lumen dilation[7-9]. Functionally, senescent endothelial and smooth muscle cells alter the vasoconstriction and vasodilation capabilities of blood vessels[10]. Structural and functional changes of aging vessels are interrelated, with vessel diameter negatively correlated with vasodilation function, and alterations in vasoconstriction and vasodilation directly influencing vessel wall diameter and tension.

Senescent vascular cells represent the core pathological mechanism of vascular aging, comprising replicative and stress-induced senescence. Replicative senescence results from telomere shortening due to repeated cell division, whereas stress-induced senescence arises from exposure to inflammatory molecules, oxidative stress, and unhealthy lifestyle factors[11,12]. Cellular senescence triggers DNA damage and is accompanied by upregulation of p53-dependent cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, such as p21Wafl/Cip1, or p16Ink4a, or both[13-15]. Thus, genes such as p16Ink4a, p21Wafl/Cip1, p53, and galactosidase beta 1 (GLB1, encoding SA-β-Gal) have frequently been utilized as core elements for constructing senescence reporter mouse models[16].

DEVELOPMENT AND CHARACTERISTICS OF SENESCENCE REPORTER MOUSE MODELS

The rapid advancement of in vivo imaging systems (IVIS) provides researchers with a novel technological platform for real-time, visual tracking of senescent cells at molecular, cellular, and tissue levels in small animals[17]. Typically, researchers insert reporter genes downstream of senescence marker gene sequences to create senescence reporter mouse models. Upon the onset of cellular senescence, the promoters of these marker genes are activated, driving the expression of reporter genes and generating detectable signals.

Senescence reporter mouse models are primarily classified based on their functions into tracing mouse models and eliminating mouse models. Tracing mouse models are used for real-time monitoring of senescent cells and lineage tracing, while eliminating mouse models investigate the roles of senescent cells in aging and age-related diseases and evaluate the therapeutic benefit of clearing senescent cells.

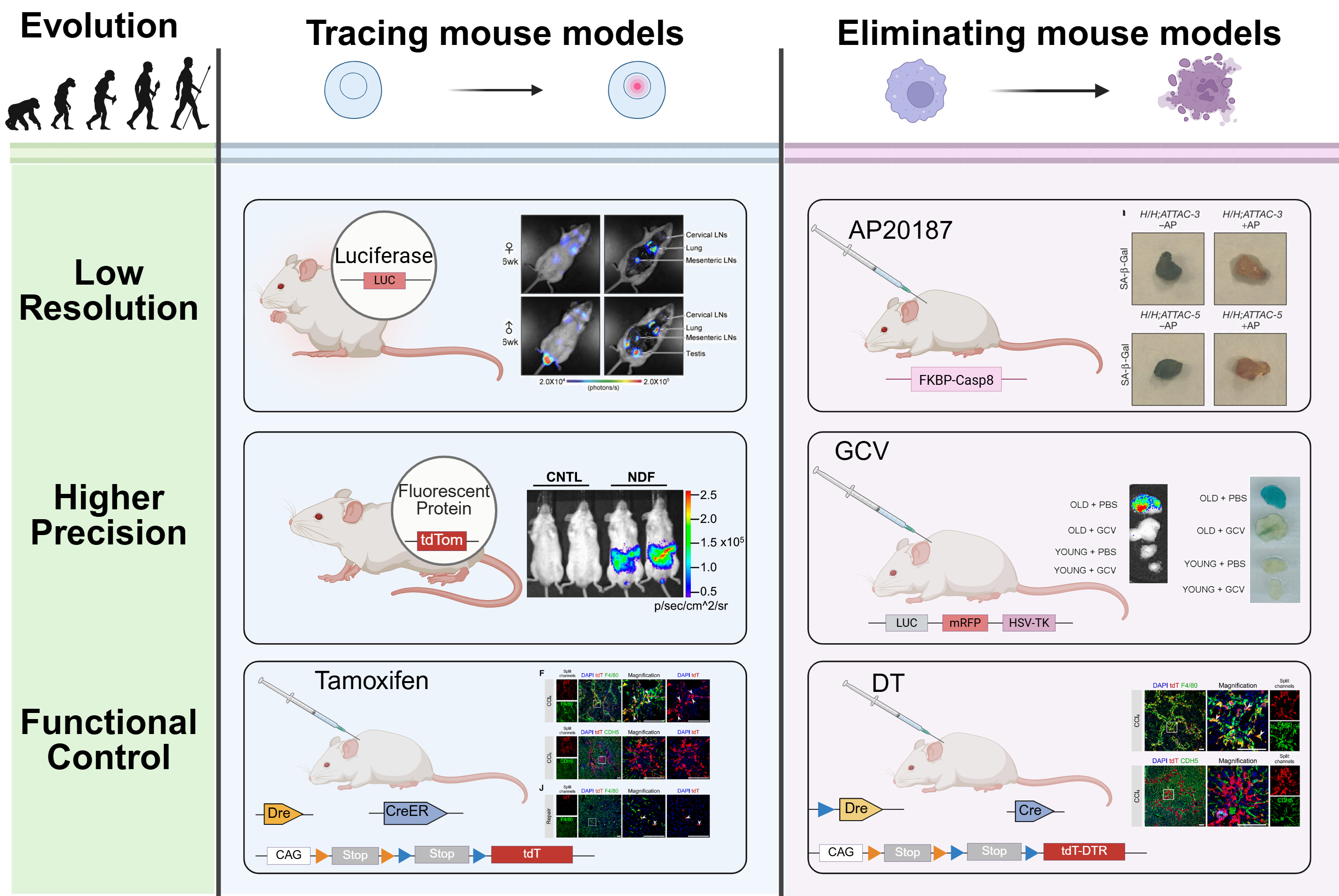

The first-generation tracing mouse models typically feature single functional elements. Since p16Ink4a is widely recognized as a senescence marker, Yamakoshi et al. constructed a humanized p16Luc reporter mouse in 2009, linking the human p16Ink4a promoter and regulatory sequences with a luciferase gene, allowing

Senescence eliminating mouse models have progressively achieved spatiotemporal and cell-specific regulation, largely due to the mature application of the Cre-LoxP system[31]. Early INK-ATTAC

Figure 1. Development and characteristics of senescence reporter mouse models. Created in BioRender. Luccy Carriman (2025) https://BioRender.com/6i1w5nr. LUC: Luciferase; tdTomato, tdTom: tandem dimer Tomato; SA-β-Gal: senescence-associated β-galactosidase; GCV: ganciclovir; mRFP: monomeric red fluorescent protein; HSV-TK: herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase; DTR: diphtheria toxin receptor; CAG: CAG promoter; CreER: Cre recombinase - estrogen receptor fusion protein; DT: diphtheria toxin; tdT: tandem dimer Tomato (tdTomato); FKBP-Caspase-8: FK506-binding protein - fused Caspase-8; CNTL: control; NDF: neonatal dermal fibroblast; LNs: lymph node(s); DAPI: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; PBS: phosphate-buffered saline.

Development and characteristics of senescence reporter mouse

| Model type | Generation | Reporter element | Model name | Construction | Optimal application | Limitation | Authors (year) | References |

| Tracing mouse models | 1st | Luciferase | p16Luc | Luciferase reporter under the exogenous p16Ink4a promoter | Real-time imaging of human p16Ink4a promoter activity | May not fully recapitulate mouse endogenous regulation | Yamakoshi et al., 2009 | [18] |

| Luciferase reporter under the murine p16Ink4a promoter | Endogenous p16Ink4a reporter enabling senescence monitor | Knock-in disrupts endogenous p16 function | Burd et al., 2013 | [19] | ||||

| p21Luc | Luciferase reporter under the exogenous p21Waf1/Cip1 promoter | First transgenic p21 reporter enabling in vivo visualization of p21 dynamics | Driven by truncated promoter and random-copy insertion | Ohtani et al., 2007 | [20] | |||

| Luciferase reporter under the murine p21Waf1/Cip1 promoter | Endogenous knock-in reporter allowing physiological p21 promoter activity | Knock-in reduces p21 dosage, potentially altering DNA damage responses | Tinkum et al., 2011 | [38] | ||||

| LacZ and Fluc integration at the p21 locus | Dual-reporter system combining luciferase for whole-body imaging | Reduced p21 expression from reporter allele | McMahon et al., 2016 | [39] | ||||

| p53RELuc | Reporter under the p53 responsive P2 element of the MDM2 promoter | Real-time bioluminescent monitoring of p53 oscillatory behavior following ionizing radiation | Restricted to MDM2 regulatory context | Hamstra et al., 2006 | [21] | |||

| Reporter under the p53 responsive element of the PUMA promoter | Visualization of chemically induced DNA damage and tissue-specific p53 activation in vivo | Reporter driven by a single p53-responsive element | Briat et al., 2008 | [40] | ||||

| 2nd | EGFP | p53REEGFP | EGFP expression under p53 core response elements from the p21 and PUMA promoters | Dual-target design distinguishes different downstream outputs of p53 and allows single-cell visualization | Limited coverage of p53 signaling | Demidenko et al., 2012 | [24] | |

| tdTomato | p16tdTom | tdTomato knock-in at exon 1α of the endogenous p16Ink4a locus | Enables single-cell visualization and isolation of p16Ink4a high cells | Knock-in reduces transcript stability | Liu et al., 2019 | [23] | ||

| Keima | Mt-Keima | pH-sensitive fluorescent protein Keima targeting of mitochondrial autography | Enables robust in vivo quantification of mitophagy across tissues | pH-dependent fluorescence spectra overlap reduces precision | Sun et al., 2017 | [25] | ||

| mCherry | Glb1-2A-mCherry (GAC) | mCherry knock-in at the Glb1 stop codon | Converts classical SA-β-Gal activity into an in vivo fluorescent reporter | SA-β-Gal/Glb1 as a single marker which is not fully specific for senescence | Sun et al., 2022 | [26] | ||

| H2B-GFP | INKBRITE | H2B-GFP expression under the p16Ink4a promoter | Provides the most sensitive and specific detection of low-level p16 activation in vivo | Restricted to lung epithelial/mesenchymal contexts | Reyes et al., 2022 | [41] | ||

| mCherry | OIS | Constitutively active MEK1 (caMEK1) expression under a doxycycline-inducible Tet-On promoter with IRES-mCherry reporter | The first to discriminate primary and secondary senescence in vivo | With insufficient assessment of other tissues, cell types, and temporal changes | Sogabe et al., 2025 | [29] | ||

| mCherry | SIS | Constitutively active MKK6 (caMKK6) expression under a doxycycline-inducible Tet-On promoter with IRES-mCherry reporter | ||||||

| 3rd | Cre-Dre | Sn-pTracer | tdTomato expression activated only in cells co-expressing Dre and Cre recombinases | Lineage trace p16Ink4a+ cells fate in a cell-type specific manner | Need cell type-specific Dre mouse lines and long-term multiple times of Tam treatment | Zhao et al., 2024 | [30] | |

| Eliminating mouse models | 1st | ATTAC | INK-ATTAC | FKBP-Caspase-8-EGFP expression under the p16Ink4a promoter with AP20187-inducible dimerization-triggered apoptosis | The first time induces p16Ink4a+ senescent cells in vivo | Missing p16-independent senescent populations and restricting tissue coverage | Baker et al., 2011 | [32] |

| p21-ATTAC | FKBP-Caspase-8-EGFP expression under the p21Waf1/Cip1 promoter with inducible apoptosis | Selective clearance of p21Waf1/Cip1+ senescent cells | Utility in aging or other senescence-associated disorders remains untested | Chandra et al., 2022 | [33] | |||

| p16-LOX-ATTAC | INK-ATTAC crossed with cell-type - specific Cre for lineage-restricted senescent cell apoptosis | Provides cell type - specific senolysis | Effects were only partially reproduced by local senolysis | Farr et al., 2023 | [42] | |||

| 2nd | 3MR | p16-3MR | Tricistronic LUC, mRFP and HSV-TK expression under the p16Ink4a promoter with Ganciclovir-induced apoptosis | First model enabling in vivo detection and selective elimination of p16Ink4a+ senescent cells | With limited organ scope and insufficient temporal analysis of dynamic senescence states | Demaria et al., 2014 | [34] | |

| p21-3MR | Tricistronic LUC, mRFP and HSV-TK expression under the p21Waf1/Cip1 promoter with Ganciclovir-induced apoptosis | First model enabling in vivo detection and selective elimination of p21Waf1/Cip1+ senescent cells | GCV-mediated clearance did not consistently reduce inflammation, and was tested with limited SASP markers | Yi et al., 2023 | [35] | |||

| ATD | p21-ATD | AkaLuc, tdTomato and DTR expression under the p21Waf1/Cip1 promoter, enabling flow sorting and DTR-mediated apoptosis | Improves upon p21-3MR by allowing simultaneous monitoring, sorting, and selective ablation of p21+ senescent cells with higher specificity | Current validation is largely liver-restricted | Chen et al., 2024 | [43] | ||

| 3rd | Cre | p16-Cre | Cre knock-in at the endogenous | Enables ablation of endogenous p16 high cells | Non-selective clearance disrupts tissue integrity and causes fibrosis | Grosse et al., 2020 | [37] | |

| p16-CreERT2-tdTomato | Tamoxifen-induced tdTomato expression in p16+ cells via p16-CreERT2 × ROSA26-lsl-tdTomato cross | Enables precise lineage tracing without developmental confounding | May cause leakiness or incomplete labeling, limiting efficiency and specificity in long-term studies | Omori et al., 2020 | [44] | |||

| p21-Cre | Cre knock-in at the endogenous p21Waf1/Cip1 locus, excising floxed targets in p21+ cells | Specifically monitor, trace, and intermittently clear p21 high cells in vivo | Targets only a small subset of cells that accumulate with aging | Wang et al., 2021 | [45] | |||

| Cre-Dre | Sn-cTracer | DTR expression activated only in cells co-expressing Dre and Cre recombinases | Enables seamless tracing and ablation of p16+ cells in a cell type - specific manner through Cre lines | Cannot perform pulse - chase lineage tracing or precise gene manipulation of p16+ cells in specific lineages | Zhao et al., 2024 | [30] |

Tracing models: p16Luc allows whole-body bioluminescent imaging[18]; p16tdT enables single-cell fluorescence detection[23]; and dual-recombinase systems permit tamoxifen-inducible lineage tracing[30]. Elimination models: INK-ATTAC mediates AP20187-induced caspase-8 - dependent apoptosis[32]; p16-3MR enables GCV-driven HSV-TK - based clearance[34]; and the dual-recombinase systems allow diphtheria

Despite the power of next-generation senescence reporter and elimination systems, several technical challenges remain. First, incomplete penetrance is a known limitation, not all senescent cells in a given tissue are labeled or eliminated by the transgene. This limitation often stems from the genomic insertion site and promoter configuration of reporter constructs[46]. For instance, Liu et al. generated a p16tdTom knock-in model by replacing one p16Ink4a allele, which resulted in hemizygous expression and partial interference with endogenous gene function[23]. In contrast, Zhao et al. inserted the fluorescent cassette into the

APPLICATION OF SENESCENCE REPORTER MOUSE MODELS IN PANVASCULAR DISEASES

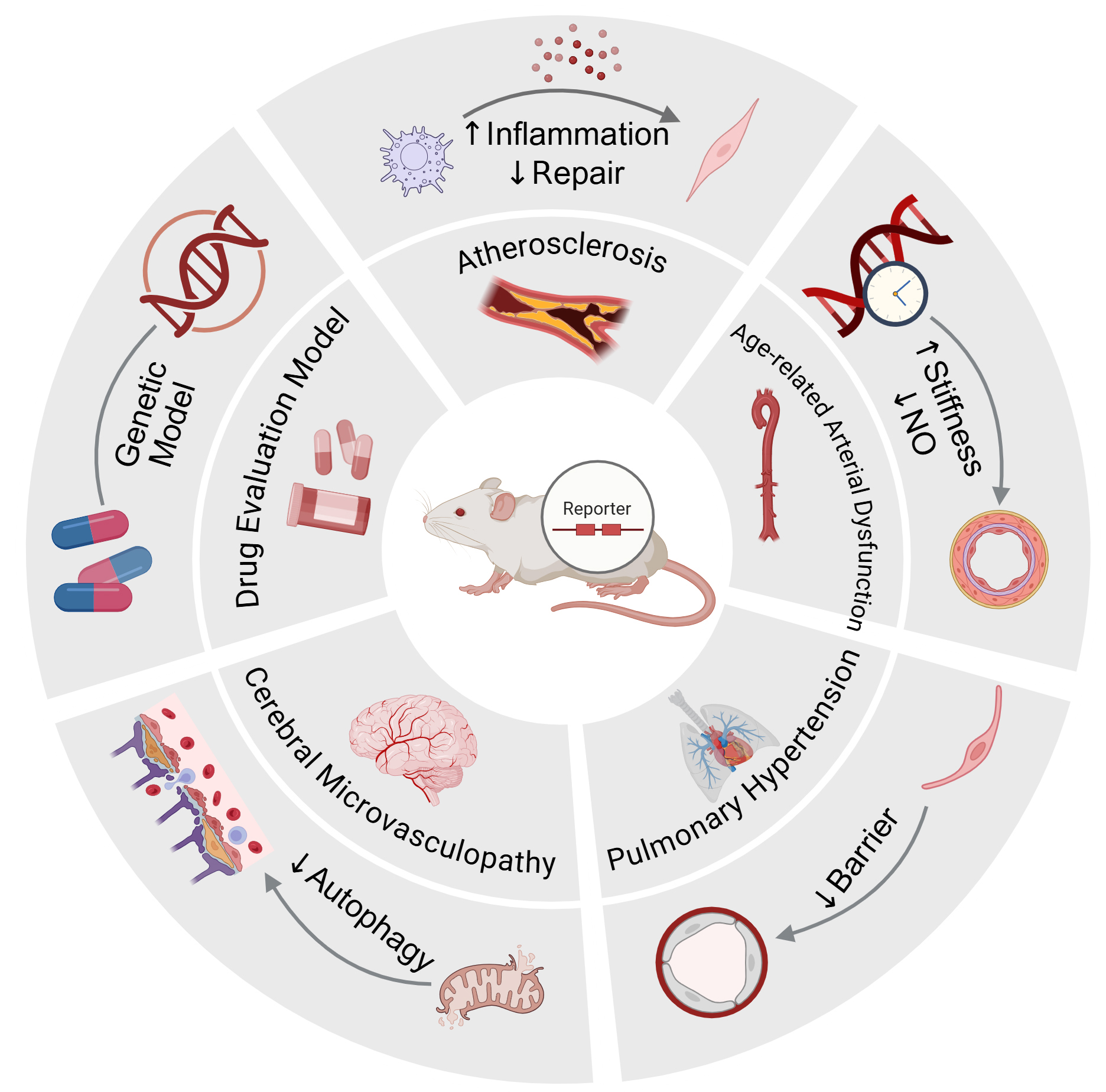

Panvascular disease research is grounded in systems biology, emphasizing the systemic and integrative nature of vascular pathologies, covering common features across cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, peripheral vascular systems, and their target organs. By elucidating the interconnections and interactions between diverse vascular pathological processes, it facilitates the establishment of comprehensive strategies for global vascular health regulation[51]. Vascular aging represents a pivotal driving factor in panvascular disease progression; thus, clarifying its underlying mechanisms is critical for intervening in disease development. Senescence reporter mouse models provide powerful technological platforms to unravel the molecular and cellular roles of senescence in panvascular diseases, as we illustrate in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Application of Senescence Reporter Mouse Models in Panvascular Disease. Created in BioRender. Luccy Carriman (2025) https://BioRender.com/m03kj4y.

The central illustration depicts senescence reporter mice used for in vivo tracing or elimination of senescent cells. Surrounding segments highlight representative disease contexts and mechanistic insights revealed by these models, including atherosclerosis, age-related arterial stiffness and endothelial dysfunction, pulmonary hypertension, and cerebral microvasculopathy. Besides, p16-3MR also serves as a genetic and pharmacologic platform for evaluating senolytics. Together, they demonstrate how reporter mouse models link cellular senescence to functional and pathological alterations across the vascular continuum.

Atherosclerosis

Age is an independent risk factor for the development of atherosclerosis[52]. Recent studies have further demonstrated that senescent cells are not merely a consequence of disease but actively promote plaque formation and progression[53]. Within major arteries such as the coronary arteries, senescent cells predominantly localize to the fibrous caps and margins of the necrotic cores within atherosclerotic lesions. Senescent vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and foam macrophages in these areas extensively express cell-cycle inhibitors such as p16Ink4a, associated with proliferative arrest and secretion of SASP factors[54]. During the early stages of lesion formation, these cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, driving local inflammation. In advanced lesions, they produce MMPs, weakening fibrous cap integrity and increasing the risk of plaque rupture. Moreover, once VSMCs become senescent, their migratory and proliferative capacities are impaired, compromising fibrous cap repair. Notably, Childs et al. reported that senescent cells within plaques secrete insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 (IGFBP3), antagonizing insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) signaling, thereby inhibiting the recruitment and extracellular matrix deposition by VSMCs, leading to fibrous cap thinning. Selective clearance of these p16high senescent cells reduced IGFBP3 levels, enhanced VSMC-mediated fibrous cap repair, and significantly improved plaque stability[55]. Studies by Roos et al. using INK-ATTAC mice, and Sadhu et al. employing p16-3MR mouse models to selectively clear hematopoietic-derived p16-positive senescent cells, further support these findings[56,57].

Recent studies have employed senescence reporter mice (p16tdTom and p16-3MR) combined with single-cell and spatial transcriptomics to systematically uncover the senescence heterogeneity of vascular smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts, and T cells within atherosclerotic lesions. This integrated multi-omics approach provides novel insights for the precise diagnosis of cellular senescence and the development of targeted senolytic interventions[58].

Collectively, senescent cells accelerate atherosclerosis progression through dual mechanisms involving inflammatory stimulation and impaired vascular repair.

Age-related arterial dysfunction

Age-related arterial stiffness, characterized by increased aortic pulse wave velocity (PWV), arises primarily from increased intrinsic mechanical stiffness and vascular wall remodeling. This remodeling is typified by collagen deposition, elastin degradation, and cross-linking of structural proteins with advanced glycation end-products (AGEs)[8,59]. Excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated oxidative stress, mainly originating from mitochondrial dysfunction and chronic low-grade inflammation, significantly impairs nitric oxide (NO)-mediated endothelial function, exacerbating arterial stiffness[60,61].

Clayton et al. employed the p16-3MR model to selectively clear p16Ink4a+ senescent cells in aged mice using GCV[62]. Following senescent cell clearance, aortic PWV significantly decreased, reverting to youthful levels, accompanied by improved endothelium-dependent relaxation. Mechanistic studies revealed enhanced NO bioavailability, reduced superoxide production, and decreased collagen I and AGE content within arterial walls.

Similarly, Mahoney et al. also utilized p16-3MR mice to investigate the pathogenic roles of senescent cells in arterial stiffness and assessed the senolytic efficacy of the natural compound 25-hydroxycholesterol

Pulmonary hypertension

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a rare chronic pulmonary vascular disease characterized by pulmonary vascular remodeling, including abnormal proliferation of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells and endothelial dysfunction[64]. Similar to atherosclerosis, PH exhibits hyperactive vascular smooth muscle cells, positioning it within the spectrum of panvascular diseases[65]. Emerging evidence suggests that multiple senescent cell types, including endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and fibroblasts, are present in PH, exacerbating disease progression[66-68].

Using p16Luc reporter mice, Born et al. identified that a significant proportion (approximately 30%) of pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells express p16Ink4a under physiological conditions. Surprisingly, subsequent studies utilizing p16-ATTAC mice and classical senolytic agents for non-selective removal of p16Ink4a+ senescent cells resulted in extensive loss of pulmonary capillary endothelial cells, worsened vascular remodeling, enhanced pulmonary artery smooth muscle proliferation, and markedly elevated right ventricular pressures[69].

Senescence also plays a significant role in other PH types, including secondary PH associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)[70]. Chronic cigarette smoke exposure induces p16Ink4a expression in alveolar epithelial and pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. SASP factors from these senescent cells activate smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts, accelerating vascular remodeling and resistance increase[71]. Kaur et al. demonstrated using p16-3MR transgenic mice that targeted clearance of p16Ink4a+ lung senescent cells via GCV significantly reversed lung senescence biomarkers, improved mitochondrial function, and alleviated airspace enlargement within five days. Thus, senolytic strategies targeting p16-positive cells have therapeutic potential to simultaneously mitigate COPD and secondary PH progression[72].

Collectively, these findings suggest that senescence of pulmonary endothelial cells functions as a double-edged sword in pulmonary vascular remodeling disorders: moderate endothelial senescence may act as a brake on pathological proliferation, thereby preventing excessive vascular remodeling, whereas excessive accumulation of senescent cells can injure lung tissue through SASP-mediated inflammation and disruption of barrier function.

Cerebral microvasculopathy

In the cerebral microvasculature, senescent cells predominantly accumulate within the endothelial cells and pericytes of the blood-brain barrier (BBB)[73,74]. As mammals age, the progressive accumulation of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations has been identified as a key driver of cellular senescence[75,76]. Concurrently, mitophagy, the selective autophagic clearance of damaged mitochondria, declines in efficiency with advancing age[77]. In various vascular pathologies, impaired mitophagy co-exists with mitochondrial dysfunction and a pro-inflammatory phenotype: uncleared, dysfunctional mitochondria trigger the secretion of cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), which in turn promotes neuroinflammation and downregulates tight junction proteins, thereby increasing BBB permeability[78,79]. Employing mt-Keima reporter mice, Tyrrell et al. demonstrated that aged animals exhibit a markedly elevated senescent burden in cerebral microvascular endothelial cells, accompanied by reduced mitophagic flux and upregulated IL-6 expression, culminating in exacerbated BBB leakage[80]. These results indicate that senescent endothelial cells and pericytes in the brain vasculature compromise barrier integrity and initiate neuroinflammatory cascades, thereby contributing to age-related central nervous system dysfunction.

Growth hormone (GH) secretion and subsequent IGF-1 secretion decline over time, implicating the

Using p16-3MR senescence reporter mice, multiple studies have shown that unconventional damage factors such as whole-brain irradiation (WBI), paclitaxel (PTX), and cisplatin/methotrexate induce p16+ senescence in cerebral microvascular endothelial and immune cells within months. This leads to increased BBB permeability, capillary rarefaction, and ultimately cognitive impairment. Administration of senolytics three months post-radiation partially restored BBB integrity, promoted capillary regeneration, and improved spatial memory, underscoring the critical value of senescence reporter mice in validating senolytics targeting and mitigating treatment side effects[83-85].

Genetic control models for evaluating senolytic drugs using p16-3MR mice

Senolytics are small molecules capable of selectively eliminating senescent cells, offering novel therapeutic strategies for multiple age-related diseases[86-88]. However, validating their targeted elimination efficacy and specific contributions to tissue function in vivo necessitates genetic models that selectively remove senescent cells as controls. The p16-3MR senescence reporter mouse model serves as an ideal functional validation system, providing a clear comparison between conditions with and without senescent cells.

In assessing the therapeutic potential of the natural flavonoid compound fisetin as a senolytic agent, Mahoney et al. effectively employed the p16-3MR model[89]. Initially, they compared two groups in ex vivo arterial function experiments from aged mice: one group underwent only GCV-mediated clearance of p16+ vascular senescent cells, resulting in significantly improved endothelial relaxation; the other group received fisetin treatment followed by GCV clearance, which did not yield additional improvement beyond the GCV-only group. This comparative approach directly demonstrated that fisetin’s vascular protective effects primarily depend on its capacity to clear p16+ senescent cells rather than nonspecific mechanisms, thereby establishing fisetin’s effectiveness as a targeted senolytic agent.

With the progressive refinement of senescence biomarker systems and the iterative advancement of reporter mouse technologies, vascular ageing should be regarded as a continuous and multifactorial process rather than a discrete event. In this context, senescence reporter mice represent powerful yet partial tools for in vivo evaluation. However, no universally accepted gold standard model has yet been established for studies of panvascular diseases. For instance, in atherosclerosis, evidence indicates that p16-driven systems exhibit inaccuracies in identifying functionally pathogenic senescent cells. Specifically, approaches based on p16, p16 reporters, or p16-linked suicide genes for the detection and/or clearance of senescent cells display notable limitations[90]. Because current models largely rely on a single biomarker, conclusions drawn under highly heterogeneous pathological contexts may be incomplete. To date, only a limited number of studies in vascular aging and related diseases have applied these senescence models. Accordingly, this review does not attempt to define a unified standard, but instead aims to provide illustrative paradigms demonstrating how senescence reporter mouse models have been applied across the spectrum of panvascular diseases.

Endothelial cells represent the most susceptible cell population to senescence across panvascular diseases[91]. The cellular composition and microenvironmental context of distinct vascular beds determine the specific manifestations and consequences of endothelial senescence. Senescence reporter mouse models not only provide powerful tools for precisely targeting endothelial cells in vivo but also enable the specific delineation of their senescent features across vascular beds, while endothelial cell-specific clearance models further allow mechanistic dissection of their functional roles in vascular disease development and progression.

DISCUSSION

Targeting senescent cells is widely considered to hold significant therapeutic potential. However, accumulating evidence indicates that simple elimination of senescent cells is not universally beneficial[34,92]. This contradiction primarily arises from the marked heterogeneity of cellular senescence, as senescent

Senescence reporter mouse models, such as p16-3MR and Sn-cTracer, have significantly advanced vascular aging research. These models use promoters of specific senescence marker genes to drive reporter elements, enabling precise in vivo labeling, tracking, and selective manipulation of senescent cells. However, classical senescence markers such as p16, p21, and p53 represent only one aspect of cellular senescence, and not all senescent cells synchronously express these markers. For example, p21 is mainly activated during early senescence, whereas p16 maintains cellular senescence status[94]. The CellAge database (http://genomics.senescence.info/cells/) first compiled 279 core senescence-driving genes and mapped their interactions via protein-interaction and co-expression networks, laying a genomic foundation[95]. Building on this, Saul et al.[96] introduced the SenMayo transcriptomic signature to calculate a quantitative “senescence score”, and Wang et al.[97] developed the human Universal Senescence Index (hUSI) across 34 cell types and 13 senescence stimuli. Together, these multi-gene, network-informed metrics overcome the specificity and sensitivity limits of SA-β-Gal and p16/p21 assays. By uniting curated gene sets with data-driven signatures, they enable scalable, high-resolution frameworks for future multi-omics mapping of cellular aging. Notably, recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility of integrating transgenic reporter models with multi-omic approaches. For example, Mazan et al. employed p16-tdTomato reporter mice in combination with

With the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) and multimodal imaging, research on vascular ageing is undergoing a methodological transformation. Beyond conventional indices such as PWV and flow-mediated dilation (FMD), recent studies have shown that AI can detect senescent features at both the cellular and organ levels. For example, deep learning models trained on nuclear morphology have been able to accurately distinguish senescent from proliferative cells across tissues, providing an automated and objective approach for senescence recognition[98]. At the vascular level, AI-based analysis of retinal and vascular imaging has demonstrated the ability to predict vascular ageing status noninvasively, establishing a foundation for image-derived vascular ageing biomarkers[99]. Integrating these AI-driven analytical pipelines with senescence reporter mouse models may ultimately construct a cross-scale framework for mapping senescent cell heterogeneity and advancing precision interventions in vascular ageing.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The Graphical Abstract was created with BioRender.com (Created in BioRender. Luccy Carriman (2025) https://BioRender.com/m5mx5wg).

Authors’ contributions

Drafted the manuscript and prepared all figures: Li H

Conceived the review and performed the literature review: Zhang Y

Supervised the work and provided critical revisions: Tian Z, Zhang S

All authors have read and approved the submitted manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC2703100 and 2023YFC3606500), the National High-Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022PUMCH-D-002 and 2023-PUMCH-E-012), and the Special Clinical Research Project of the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (20244Y0022).

Conflicts of interest

Zhang Y serves as a member of the Youth Editorial Board of Vessel Plus and as a Guest Editor for the Special Issue Panvascular Aging. Zhang Y was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, and decision making. The other authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Zhou X, Yu L, Zhao Y, Ge J. Panvascular medicine: an emerging discipline focusing on atherosclerotic diseases. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:4528-31.

2. Liberale L, Badimon L, Montecucco F, Lüscher TF, Libby P, Camici GG. Inflammation, aging, and cardiovascular disease: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:837-47.

3. North BJ, Sinclair DA. The intersection between aging and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2012;110:1097-108.

4. Ungvari Z, Tarantini S, Sorond F, Merkely B, Csiszar A. Mechanisms of vascular aging, a geroscience perspective: JACC focus seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:931-41.

6. McHugh D, Gil J. Senescence and aging: causes, consequences, and therapeutic avenues. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:65-77.

7. Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part I: aging arteries: a “set up” for vascular disease. Circulation. 2003;107:139-46.

8. Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1318-27.

9. Fritze O, Romero B, Schleicher M, et al. Age-related changes in the elastic tissue of the human aorta. J Vasc Res. 2012;49:77-86.

10. Pietri P, Stefanadis C. Cardiovascular aging and longevity: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:189-204.

11. Greider CW. Telomeres and senescence: the history, the experiment, the future. Curr Biol. 1998;8:R178-81.

12. Toussaint O, Medrano EE, von Zglinicki T. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of stress-induced premature senescence (SIPS) of human diploid fibroblasts and melanocytes. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35:927-45.

13. Ohtani N, Yamakoshi K, Takahashi A, Hara E. The p16INK4a-RB pathway: molecular link between cellular senescence and tumor suppression. J Med Invest. 2004;51:146-53.

14. Herbig U, Wei W, Dutriaux A, Jobling WA, Sedivy JM. Real-time imaging of transcriptional activation in live cells reveals rapid up-regulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor gene CDKN1A in replicative cellular senescence. Aging Cell. 2003;2:295-304.

15. Itahana K, Dimri G, Campisi J. Regulation of cellular senescence by p53. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:2784-91.

16. Lee BY, Han JA, Im JS, et al. Senescence-associated β-galactosidase is lysosomal β-galactosidase. Aging Cell. 2006;5:187-95.

17. Liu S, Su Y, Lin MZ, Ronald JA. Brightening up biology: advances in luciferase systems for in vivo imaging. ACS Chem Biol. 2021;16:2707-18.

18. Yamakoshi K, Takahashi A, Hirota F, et al. Real-time in vivo imaging of p16Ink4a reveals cross talk with p53. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:393-407.

19. Burd CE, Sorrentino JA, Clark KS, et al. Monitoring tumorigenesis and senescence in vivo with a p16INK4a-luciferase model. Cell. 2013;152:340-51.

20. Ohtani N, Imamura Y, Yamakoshi K, et al. Visualizing the dynamics of p21Waf1/Cip1 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor expression in living animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15034-9.

21. Hamstra DA, Bhojani MS, Griffin LB, Laxman B, Ross BD, Rehemtulla A. Real-time evaluation of p53 oscillatory behavior in vivo using bioluminescent imaging. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7482-9.

22. Pan C, Cai R, Quacquarelli FP, et al. Shrinkage-mediated imaging of entire organs and organisms using uDISCO. Nat Methods. 2016;13:859-67.

23. Liu JY, Souroullas GP, Diekman BO, et al. Cells exhibiting strong p16INK4a promoter activation in vivo display features of senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:2603-11.

24. Demidenko ZN, Korotchkina LG, Gudkov AV, Blagosklonny MV. Paradoxical suppression of cellular senescence by p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9660-4.

26. Sun J, Wang M, Zhong Y, et al. A Glb1-2A-mCherry reporter monitors systemic aging and predicts lifespan in middle-aged mice. Nat Commun. 2022;13:7028.

27. Muris Consortium. A single-cell transcriptomic atlas characterizes ageing tissues in the mouse. Nature. 2020;583:590-5.

28. Biran A, Zada L, Abou Karam P, et al. Quantitative identification of senescent cells in aging and disease. Aging Cell. 2017;16:661-71.

29. Sogabe Y, Shibata H, Kabata M, et al. Characterizing primary and secondary senescence in vivo. Nat Aging. 2025;5:1568-88.

30. Zhao H, Liu Z, Chen H, et al. Identifying specific functional roles for senescence across cell types. Cell. 2024;187:7314-7334.e21.

31. Tsien JZ, Huerta PT, Tonegawa S. The essential role of hippocampal CA1 NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity in spatial memory. Cell. 1996;87:1327-38.

32. Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Tchkonia T, et al. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature. 2011;479:232-6.

33. Chandra A, Lagnado AB, Farr JN, et al. Targeted clearance of p21- but not p16-positive senescent cells prevents radiation-induced osteoporosis and increased marrow adiposity. Aging Cell. 2022;21:e13602.

34. Demaria M, Ohtani N, Youssef SA, et al. An essential role for senescent cells in optimal wound healing through secretion of PDGF-AA. Dev Cell. 2014;31:722-33.

35. Yi Z, Ren L, Wei Y, et al. Generation of a p21 reporter mouse and its use to identify and eliminate p21high cells in vivo. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:5565.

36. Baker DJ, Childs BG, Durik M, et al. Naturally occurring p16Ink4a-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Nature. 2016;530:184-9.

37. Grosse L, Wagner N, Emelyanov A, et al. Defined p16High senescent cell types are indispensable for mouse healthspan. Cell Metab. 2020;32:87-99.e6.

38. Tinkum KL, Marpegan L, White LS, et al. Bioluminescence imaging captures the expression and dynamics of endogenous p21 promoter activity in living mice and intact cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:3759-72.

39. McMahon M, Frangova TG, Henderson CJ, Wolf CR. Olaparib, monotherapy or with ionizing radiation, exacerbates DNA damage in normal tissues: insights from a new p21 reporter mouse. Mol Cancer Res. 2016;14:1195-203.

40. Briat A, Vassaux G. A new transgenic mouse line to image chemically induced p53 activation in vivo. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:683-8.

41. Reyes NS, Krasilnikov M, Allen NC, et al. Sentinel p16INK4a+ cells in the basement membrane form a reparative niche in the lung. Science. 2022;378:192-201.

42. Farr JN, Saul D, Doolittle ML, et al. Local senolysis in aged mice only partially replicates the benefits of systemic senolysis. J Clin Invest. 2023;133:e162519.

43. Chen M, Wu G, Lu Y, et al. A p21-ATD mouse model for monitoring and eliminating senescent cells and its application in liver regeneration post injury. Mol Ther. 2024;32:2992-3011.

44. Omori S, Wang TW, Johmura Y, et al. Generation of a p16 reporter mouse and its use to characterize and target p16high cells in vivo. Cell Metab. 2020;32:814-828.e6.

45. Wang B, Wang L, Gasek NS, et al. An inducible p21-Cre mouse model to monitor and manipulate p21-highly-expressing senescent cells in vivo. Nat Aging. 2021;1:962-73.

46. Battison AS, Merrill JR, Borniger JC, Lyons SK. The regulation of reporter transgene expression for diverse biological imaging applications. Npj Imaging. 2025;3:9.

47. Blewitt M, Whitelaw E. The use of mouse models to study epigenetics. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a017939.

48. Carver CM, Rodriguez SL, Atkinson EJ, et al. IL-23R is a senescence-linked circulating and tissue biomarker of aging. Nat Aging. 2025;5:291-305.

49. Stavrou M, Philip B, Traynor-White C, et al. A rapamycin-activated Caspase 9-based suicide gene. Mol Ther. 2018;26:1266-76.

50. Bahour N, Bleichmar L, Abarca C, Wilmann E, Sanjines S, Aguayo-Mazzucato C. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive cells in a mouse transgenic model does not change β-cell mass and has limited effects on their proliferative capacity. Aging. 2023;15:441-58.

51. Yan W, Zhang Y, Dai Y, Ge J. Application of crotonylation modification in panvascular diseases. J Drug Target. 2024;32:996-1004.

52. Tyrrell DJ, Goldstein DR. Ageing and atherosclerosis: vascular intrinsic and extrinsic factors and potential role of IL-6. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18:58-68.

53. Wang JC, Bennett M. Aging and atherosclerosis: mechanisms, functional consequences, and potential therapeutics for cellular senescence. Circ Res. 2012;111:245-59.

54. Childs BG, Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Conover CA, Campisi J, van Deursen JM. Senescent intimal foam cells are deleterious at all stages of atherosclerosis. Science. 2016;354:472-7.

55. Childs BG, Zhang C, Shuja F, et al. Senescent cells suppress innate smooth muscle cell repair functions in atherosclerosis. Nat Aging. 2021;1:698-714.

56. Roos CM, Zhang B, Palmer AK, et al. Chronic senolytic treatment alleviates established vasomotor dysfunction in aged or atherosclerotic mice. Aging Cell. 2016;15:973-7.

57. Sadhu S, Decker C, Sansbury BE, et al. Radiation-induced macrophage senescence impairs resolution programs and drives cardiovascular inflammation. J Immunol. 2021;207:1812-23.

58. Mazan-Mamczarz K, Tsitsipatis D, Childs BG, et al. Single-cell and spatial transcriptomics map senescent vascular cells in arterial remodeling during atherosclerosis in mice. Nat Aging. 2025;5:1528-47.

59. Clayton ZS, Brunt VE, Hutton DA, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-mediated inflammation and remodeling of the extracellular matrix underlies aortic stiffening induced by the common chemotherapeutic agent doxorubicin. Hypertension. 2021;77:1581-90.

60. Rossman MJ, Gioscia-Ryan RA, Clayton ZS, Murphy MP, Seals DR. Targeting mitochondrial fitness as a strategy for healthy vascular aging. Clin Sci. 2020;134:1491-519.

61. Steven S, Frenis K, Oelze M, et al. Vascular inflammation and oxidative stress: major triggers for cardiovascular disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:7092151.

62. Clayton ZS, Rossman MJ, Mahoney SA, et al. Cellular senescence contributes to large elastic artery stiffening and endothelial dysfunction with aging: amelioration with senolytic treatment. Hypertension. 2023;80:2072-87.

63. Mahoney SA, Darrah MA, Venkatasubramanian R, et al. Late life supplementation of 25-hydroxycholesterol reduces aortic stiffness and cellular senescence in mice. Aging Cell. 2025;24:e70118.

65. Hu Y, Zhao Y, Li P, Lu H, Li H, Ge J. Hypoxia and panvascular diseases: exploring the role of hypoxia-inducible factors in vascular smooth muscle cells under panvascular pathologies. Sci Bull. 2023;68:1954-74.

66. Ramadhiani R, Ikeda K, Miyagawa K, et al. Endothelial cell senescence exacerbates pulmonary hypertension by inducing juxtacrine Notch signaling in smooth muscle cells. iScience. 2023;26:106662.

67. Wang AP, Yang F, Tian Y, et al. Pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell senescence promotes the proliferation of PASMCs by paracrine IL-6 in hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Front Physiol. 2021;12:656139.

68. van der Feen DE, Bossers GPL, Hagdorn QAJ, et al. Cellular senescence impairs the reversibility of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Sci Transl Med. 2020:12.

69. Born E, Lipskaia L, Breau M, et al. Eliminating senescent cells can promote pulmonary hypertension development and progression. Circulation. 2023;147:650-66.

71. Cottage CT, Peterson N, Kearley J, et al. Targeting p16-induced senescence prevents cigarette smoke-induced emphysema by promoting IGF1/Akt1 signaling in mice. Commun Biol. 2019;2:307.

72. Kaur G, Muthumalage T, Rahman I. Clearance of senescent cells reverts the cigarette smoke-induced lung senescence and airspace enlargement in p16-3MR mice. Aging Cell. 2023;22:e13850.

73. Zlokovic BV. Neurovascular pathways to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:723-38.

74. Kim SY, Cheon J. Senescence-associated microvascular endothelial dysfunction: A focus on the blood-brain and blood-retinal barriers. Ageing Res Rev. 2024;100:102446.

75. Wang C, Yang K, Liu X, et al. MAVS antagonizes human stem cell senescence as a mitochondrial stabilizer. Research. 2023;6:0192.

76. Zhou X, Zhu X, Wang W, et al. Comprehensive cellular senescence evaluation to aid targeted therapies. Research. 2025;8:0576.

77. Onishi M, Yamano K, Sato M, Matsuda N, Okamoto K. Molecular mechanisms and physiological functions of mitophagy. EMBO J. 2021;40:e104705.

78. Zhou X, Xu SN, Yuan ST, et al. Multiple functions of autophagy in vascular calcification. Cell Biosci. 2021;11:159.

79. Zhang Y, Weng J, Huan L, Sheng S, Xu F. Mitophagy in atherosclerosis: from mechanism to therapy. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1165507.

80. Tyrrell DJ, Blin MG, Song J, Wood SC, Goldstein DR. Aging impairs mitochondrial function and mitophagy and elevates interleukin 6 within the cerebral vasculature. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e017820.

81. Junnila RK, List EO, Berryman DE, Murrey JW, Kopchick JJ. The GH/IGF-1 axis in ageing and longevity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9:366-76.

82. Gulej R, Csik B, Faakye J, et al. Endothelial deficiency of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor leads to blood-brain barrier disruption and accelerated endothelial senescence in mice, mimicking aspects of the brain aging phenotype. Microcirculation. 2024;31:e12840.

83. Gulej R, Nyúl-Tóth Á, Ahire C, et al. Elimination of senescent cells by treatment with Navitoclax/ABT263 reverses whole brain irradiation-induced blood-brain barrier disruption in the mouse brain. Geroscience. 2023;45:2983-3002.

84. Ahire C, Nyul-Toth A, DelFavero J, et al. Accelerated cerebromicrovascular senescence contributes to cognitive decline in a mouse model of paclitaxel (Taxol)-induced chemobrain. Aging Cell. 2023;22:e13832.

85. Csik B, Vali Kordestan K, Gulej R, et al. Cisplatin and methotrexate induce brain microvascular endothelial and microglial senescence in mouse models of chemotherapy-associated cognitive impairment. Geroscience. 2025;47:3447-59.

86. Chaib S, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL. Cellular senescence and senolytics: the path to the clinic. Nat Med. 2022;28:1556-68.

87. Xu M, Pirtskhalava T, Farr JN, et al. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat Med. 2018;24:1246-56.

88. Kroemer G, Maier AB, Cuervo AM, et al. From geroscience to precision geromedicine: understanding and managing aging. Cell. 2025;188:2043-62.

89. Mahoney SA, Venkatasubramanian R, Darrah MA, et al. Intermittent supplementation with fisetin improves arterial function in old mice by decreasing cellular senescence. Aging Cell. 2024;23:e14060.

90. Garrido AM, Kaistha A, Uryga AK, et al. Efficacy and limitations of senolysis in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2022;118:1713-27.

91. Bloom SI, Islam MT, Lesniewski LA, Donato AJ. Mechanisms and consequences of endothelial cell senescence. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20:38-51.

92. Sophia AM, Samuel IB, Douglas RS, Anthony JD, Matthew JR, Clayton ZS. Mechanisms of cellular senescence-induced vascular aging: evidence of senotherapeutic strategies. J Cardiovasc Aging. 2025;5:6.

93. Ding Y, Zuo Y, Zhang B, et al. Comprehensive human proteome profiles across a 50-year lifespan reveal aging trajectories and signatures. Cell. 2025;188:5763-5784.e26.

94. Dulić V, Beney GE, Frebourg G, Drullinger LF, Stein GH. Uncoupling between phenotypic senescence and cell cycle arrest in aging p21-deficient fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6741-54.

95. Avelar RA, Ortega JG, Tacutu R, et al. A multidimensional systems biology analysis of cellular senescence in aging and disease. Genome Biol. 2020;21:91.

96. Saul D, Kosinsky RL, Atkinson EJ, et al. A new gene set identifies senescent cells and predicts senescence-associated pathways across tissues. Nat Commun. 2022;13:4827.

97. Wang J, Zhou X, Yu P, et al. A transcriptome-based human universal senescence index (hUSI) robustly predicts cellular senescence under various conditions. Nat Aging. 2025;5:1159-75.

98. Duran I, Pombo J, Sun B, et al. Detection of senescence using machine learning algorithms based on nuclear features. Nat Commun. 2024;15:1041.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].