Stem cell-based strategies for vascular aging: from mechanistic insights to clinical translation

Abstract

Vascular aging serves as a key driver of cardiovascular diseases, contributing significantly to the increasing global burden of morbidity and mortality. During vascular aging, stem cell senescence perturbs vascular homeostasis through impaired regeneration, increased oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation. Ultimately, it accelerates the development of vascular pathologies, such as atherosclerosis and aneurysm formation. This review aims to elucidate the roles of senescent vascular stem cells in the progression of vascular aging and also to explore the therapeutic potential of stem cell-based interventions in the management of cardiovascular diseases. It comprehensively includes various stem cell types, as well as their derived substances, elaborating on their roles in vascular aging and repair. Centered on "vascular stem cell senescence", it systematically elucidates the causal relationships among stem cell senescence, vascular homeostasis disruption, and the development of cardiovascular diseases, thereby constructing a focused and coherent mechanistic framework for understanding the pathological process of vascular aging. By integrating cross-system factors, including gut microbiota dysbiosis, renin-angiotensin system dysregulation, and abnormal hemodynamics, this review reveals the multi-system interactions underlying vascular aging. Moreover, it emphasizes translational rigor by not only introducing preclinical advancements but also objectively analyzing technical bottlenecks and clinical limitations, and further pointing out directions for future research. Overall, this review clarifies the roles of senescent vascular stem cells in vascular aging and the therapeutic potential of stem cell-based interventions for cardiovascular diseases, providing valuable references for promoting the clinical translation of stem cell-based strategies in the management of vascular aging-related cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the most prevalent health issues with high incidence, disability, and mortality rates, threatening human health. Population aging contributes to a rising incidence and greater severity of CVDs. Individual risk increases with age, as vascular aging occurs in parallel with structural and functional decline across multiple organ systems, a situation now widely acknowledged as a major public health challenge. “Aging” relates to time-dependent functional decline at the organismal or organ level, seen in physiological systems. The annual CVD incidence rate of China is projected to increase from 0.74% in 2021 to 0.97% by 2030, and the yearly mortality rate is expected to plateau at 0.44% till 2030[1]. The aggregate amount of CVD deaths would rise by 39 million in total between 2016 and 2030[2]. From 2025 to 2050, crude CVD mortality in Asia is anticipated to rise by 91.2%, despite a 23.0% decrease in the age-standardized cardiovascular mortality rate[3]. CVDs encompass a range of conditions, including atherosclerosis (AS), hypertension, coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, aortic aneurysm and related disorders. Thus, there is an urgent need for effective therapeutic interventions.

STEM CELLS IN VASCULAR DEVELOPMENT AND HOMEOSTASIS

The cardiovascular system primarily originates from the mesoderm. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from the extraembryonic mesoderm form blood islands. The marginal cells of blood islands differentiate into endothelial cells (ECs), muscle cells, and other cell types to form blood vessels. Through continuous development, these blood vessels develop into a vascular network that ultimately gives rise to the cardiovascular system. Undifferentiated MSCs remain in adult tissues, maintaining vascular homeostasis.

MSCs are characterized by high pluripotency, anti-inflammatory and self-renewal capabilities. They can also resist apoptosis and promote angiogenesis along with the capacity to differentiate into ECs, vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), pericytes and others[4,5]. In addition to their multipotency in differentiation, MSCs are advantageous because they can be sourced from a variety of tissues, including the umbilical cord, bone marrow, adipose tissue, and others[6]. Notably, the multipotent stem cells residing in the vascular wall, which are located in the adventitia of the arteries, are a subset of MSCs. They express typical MSC markers and can differentiate into pericytes and VSMCs, thereby contributing to the repair of the injured vascular wall[7]. Compared to bone marrow-derived MSCs (BMSCs), vascular wall-derived MSCs exhibit superior efficiency in treating vascular diseases such as hypertension, ischemic conditions, and congenital vascular lesions[8]. Therefore, they are often regarded as an effective therapeutic approach for vascular aging.

VASCULAR STEM CELL SENESCENCE: MECHANISMS AND IMPLICATIONS

Stem cells, due to their long-term residence in tissues and their inability to regenerate from more primitive cell types, are vulnerable to the accumulation of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) damage. This damage can stem from various sources, including radiation exposure and contact with exogenous chemicals. This damage leads to persistent changes in chromatin structure, including DNA methylation and histone modifications[9]. These alterations, in turn, contribute to the accumulation of DNA fragments that promote cellular senescence often called "DNA scars" in senescent cells[10]. Different from “aging”, “senescence” means irreversible cell-cycle arrest at the microscopic level, caused by molecular damage and marked by biomarkers and a pro-inflammatory phenotype. Epigenetic modifications have been associated with driving mammalian aging[11,12]. Moreover, under the influence of external diseases such as diabetes, the intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in stem cells increase, leading to inflammation and cellular damage[13]. Multiple factors can initiate pathological conditions in stem cells, such as oxidative stress, abnormal activation of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), intestinal dysbiosis, and hemodynamic changes. These factors together induce DNA degradation, vascular inflammation, epigenetic phenotype changes, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Vascular stem cell senescence contributes to vascular aging and is associated with pathological conditions in the cardiovascular system. For example, in aged mice, oral administration of Quercetin (a senolytic agent) significantly reduced senescent cell markers in the aorta tunica media. Endothelium-dependent vasodilation function was enhanced, linked to increased nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability[14]. This section will focus on key factors and mechanisms underlying vascular stem cell senescence, as well as the adverse effects mediated by senescent stem cells.

Factors inducing pathological changes in stem cells and associated vascular diseases

Excessive oxidative stress promotes the senescence of stem cells

ROS is the primary cause of most oxidative stress. However, low levels of ROS play a beneficial role in maintaining stem cell stemness and promoting angiogenesis via the hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α)/vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway[15]. Under physiological conditions, ROS in mitochondria and the antioxidant system maintains a balanced state. However, under induction by microenvironments such as hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia, radiation, and cytokines, this balance is disrupted, leading to excessive ROS accumulation. Excessive ROS can accumulate endogenously through the mitochondrial electron transport chain (due to electron leakage), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases (Nox)[16], such as Nox1/2/4, a reduction in the expression and activity of the acetylase Sirtuin2 (Sirt2)[17] and inflammatory cells[15]. Exogenous ROS accumulation can occur through exposure to invasive substances[18] or through imbalances in internal components such as H2O2 and high glucose levels[19,20]. ROS can cause senescence and apoptosis of stem cells and progenitor cells (such as MSCs and pericytes)[13]. Specifically, ROS induces DNA double-strand breaks in MSCs, leading to a higher expression of their senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), increased secretion of pro-inflammatory factors (interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1)), which exacerbate vascular inflammation and enhance atherosclerotic plaque formation[21].

Furthermore, reducing the expression of antioxidant genes (such as heme oxygenase 1) aggravates pericellular damage. In this situation, the dysregulated expression of collagen (collagen type IV alpha 1 chain and collagen type IV alpha 2 chain) and integrins (integrin subunit alpha 5 and integrin subunit beta 3) impairs cell-matrix signaling, leading to the senescence of MSCs. This is manifested by a reduced ability of vascular formation, lower VEGF levels, and decreased autophagy activity[22].

Dysregulation of RAS induces stem cell senescence

RAS functions as the primary endocrine axis for regulating blood pressure. Under the modulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and ACE2, renin is converted into either angiotensin II (Ang II) or angiotensin-(1-7) (Ang-(1-7)). Ang II exhibits vasoconstrictive, pro-inflammatory, and profibrotic effects, while Ang-(1-7) exerts protective effects such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and vasodilation on blood vessels[23,24]. Soluble ACE2 converts Ang II to Ang-(1-7), activating Mas receptor (MasR) to improve vascular repair (by enhancing NO and reducing ROS). Activation of the ACE2/MasR axis promotes hematopoietic progenitor/stem cells (HSPCs) recruitment to ischemic areas, enhancing vascular regeneration[25,26]. Ang-(1-7) enhances the survival and proliferative ability of CD34+ HPSCs, including endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs)[25], through the Mas/phosphoinositide 3-kinase/serine/threonine kinase (Mas/PI3K/Akt) pathway[25]. The imbalance in the ACE/ACE2 results in disruptions to the equilibrium between Ang-(1-7) and Ang II. Additionally, the loss of MasR disrupts the ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/Mas axis, exacerbating the activity of the ACE/Ang II/Ang II type 1 receptor (AT1R) axis. This dysregulation promotes vascular inflammation and fibrosis[27,28], triggering oxidative stress, inflammation (as indicated by increased nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB)), and NO deficiency (due to decreased endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS))[23].

Intestinal flora dysbiosis accelerates stem cell senescence

Adverse alterations in gut flora composition can promote vascular senescence by disrupting the balance of specific substances, which then affect blood vessels through the systemic circulation. Dysbiosis-induced upregulation of trimethylamine N-oxide/flavin-containing monooxygenase pathway is involved in the pathogenesis of hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, and stroke[29-31]; Increased ROS and pro-inflammatory factors (IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)) initiate apoptosis of MSCs, EPCs and other stem cells, worsening vascular inflammation; Moreover, dysbiosis inhibits the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK)/eNOS signaling pathway, reducing the bioavailability of NO and impair AMPK activity[32]; these comprehensive factors contribute to extensive damage to EPCs, resulting in their telomere loss and chronic inflammation. Endothelium-dependent vasodilation function declines (reduced NO) and persistent inflammation and oxidative stress promote AS[33]. Dysbiosis (the elevation of pro-inflammatory bacteria and the reduction of beneficial ones[34]) can also interact with the RAS system. For instance, the increased expression of pro-inflammatory TNF-α is associated with dysbiosis[27], which influences the proliferation and retention of CD34+ cells, including EPCs and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs).

Hemodynamic deterioration accelerates plaques of the vascular wall and senescence of stem cells

In the curved segments of arteries where blood flow is disturbed, ECs are subjected to low shear stress, which induces inflammation and functional abnormalities and accelerates the development of atherosclerotic plaques. As blood vessels become narrower and less elastic, turbulence increases and shear stress elevates, further worsening plaque instability and arterial wall remodeling processes[35-37]. In addition, shear stress can induce an oxidative stress response in MSCs. On the one hand, it directly inflicts damage to DNA, telomere, and mitochondria, activates the DNA damage response and the tumor protein p53 (p53)/p21 and p16/retinoblastoma protein pathways, leading to cell cycle arrest. On the other hand, it exacerbates metabolic disorders through the “ROS-mitochondrial damage” vicious cycle and activates pathways such as NF-κB, inducing the SASP. Ultimately, this results in the loss of proliferative capacity and functional decline of MSCs, accelerating the senescence process[38]. A study has reported that blood flow restriction exercise induces regional hypoxia, which upregulates the ACE2-Ang-(1-7)-MasR axis (relying on HIF-1α-mediated transcriptional regulation). Moreover, it promotes the migration and vasculogenic functions of HSPCs via C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) and VEGF receptor (VEGFR) signaling pathways[39], suggesting that altering hemodynamics could remarkably influence blood vessel states through affecting multiple factors, including oxidative stress levels and RAS status.

Inflammatory microenvironment induces stem cell senescence

The accumulation of pro-inflammatory factors and inflammation-prone environmental changes is a pivotal factor inducing stem cell senescence. Increased inflammatory signals such as interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β)[40], TNF-α, and IL-6 inhibit forkhead box O transcription factors and increase the production of ROS, leading to DNA damage[41] and epigenetic alterations (such as abnormal methylation). Senescence-related genes, including von Willebrand factor (vWF) and Epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 15 (EPS15) homology domain-containing protein 3 (EHD3), are upregulated, while stem cell maintenance genes, such as GATA binding protein 2 and CXCR4, are downregulated in HSCs[34], thereby impairing their stemness. During senescence, the abnormal activation of IL-27 receptor signaling promotes the inflammatory response and functional damage of HSCs via the Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 1/3 (STAT1/3) pathway[42]. During aging, mesenchymal and adipocyte progenitor cells usually shift from osteogenesis to adipogenesis. This enhanced adipogenic property impairs vascular microenvironment stability. Conversely, oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and endocrine disorders in the microenvironment regulate bone marrow adipocytes and worsen their impact on homeostasis[43].

Persistent inflammatory signals including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β can activate the NF-κB pathway within stem cells, inducing the secretion of large amounts of profibrotic cytokines, such as TGF-β1, platelet-derived growth factor and promoting a transition towards a profibrotic phenotype. Under the influence of TGF-β1, MSCs undergo "myofibroblast transformation" enhancing their ability to synthesize collagen I/III[44]. When stimulated by inflammatory factors, EPCs experience impaired differentiation and fail to effectively repair damaged endothelium[45]. Instead, they secrete fibronectin, which promotes extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition. Abnormally activated HSCs release pro-inflammatory myeloid cells such as monocytes, further exacerbating local inflammation and creating a "inflammation-fibrosis" positive feedback loop[46]. In addition, the presence of the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 amplifies the SASP effect through the STAT3 signaling pathway[47,48]. Similarly, TNF-α binds to its receptor TNFR1, activating the c-Jun N-terminal kinase/38-kilodalton mitogen-activated protein kinase (JNK/p38) mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, which in turn promotes the expression of the p53/p21 senescence pathway[42]. This demonstrates a positive feedback loop of “inflammation-stem cell senescence-more severe inflammation”[49]. Within the plaque, MSCs are transformed into myofibroblasts under the stimulation of chronic inflammation and oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL). These myofibroblasts synthesize a large amount of collagen to form a "fibrous cap". If the fibrous cap becomes excessively fibrotic and fragile due to an imbalance in degradation mediated by matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), it is prone to rupture, which can trigger acute thrombotic events. Meanwhile, fibrosis of the media leads to arterial wall stiffness and increased blood pressure fluctuations[50].

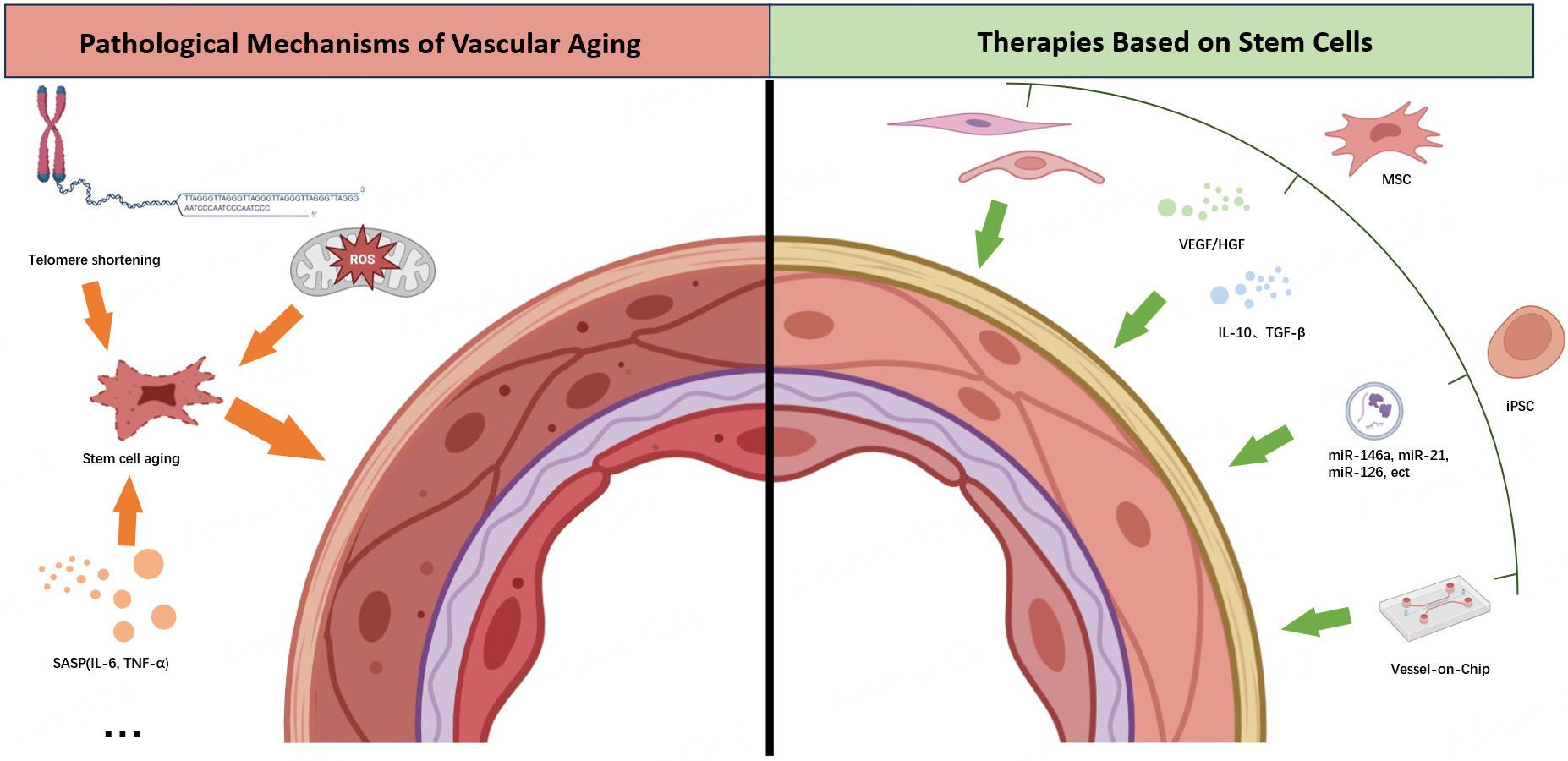

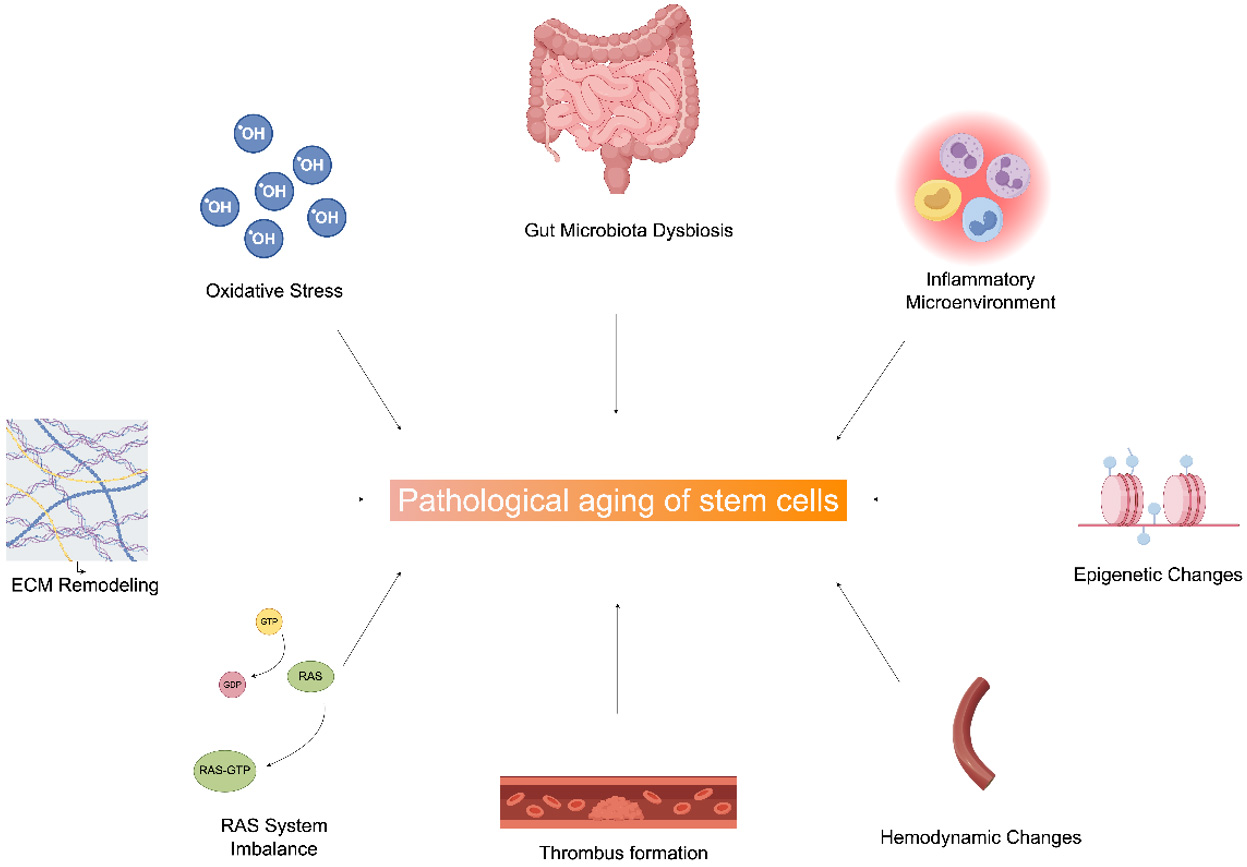

In total, the intricate comprehensive effects of oxidative stress, RAS system imbalance, gut microbiota dysbiosis, microenvironmental inflammation, and hemodynamic changes accelerate stem cell senescence [Figure 1].

Figure 1. Schematic of the regulatory network driving stem cell pathological aging. Multiple factors, including Oxidative Stress, Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis, Inflammatory Microenvironment, ECM Remodeling, RAS System Imbalance, Thrombus Formation, Hemodynamic Changes, and Epigenetic Changes, promote stem cell pathological aging (solid arrows denote inducing effects). ECM: Extracellular matrix; RAS: renin-angiotensin system. (By Figdraw, ID: YASWOe3f11).

Change of stem cells and vicious outcomes

DNA degradation of stem cells causes senescence

DNA degradation can trigger cellular senescence by inducing genomic instability and activating cellular stress responses, which in turn impair cellular function and contribute to the senescence process. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) can be activated upon DNA double-strand breaks in eukaryotic cells facilitating the repair of DNA damage. However, defective ATM can accelerate cellular senescence caused by DNA damage[51]. Radiation can also cause DNA damage and increase the levels of ROS. The excessive accumulation of ROS can lead to the loss of stemness in MSCs, EPCs, and pericytes[52]. Specifically, the accumulation of ROS activates the p53/p21 pathway through telomere shortening and DNA damage, which inhibits the proliferation of MSCs and induces senescence[53]. In EPCs, ROS activates p38 MAPK, which subsequently inhibits the mitochondrial fusion protein Mfn2, leading to mitochondrial fragmentation and further amplifying the oxidative stress signal[54]. The ROS-mediated B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2)/cytochrome c/apoptosis-inducing factor pathway induces pericyte apoptosis[55]. Moreover, disrupted DNA reduces the immune regulatory function of MSCs, thereby inhibiting their vascular regeneration capacity. Consequently, the progression of AS is exacerbated[21].

Additionally, telomere shortening is a primary contributor to chromosomal and DNA degradation. Telomeres are DNA-protein complexes located at the ends of chromosomes, where they protect against damage caused by chemical modifications or enzymatic degradation. However, when telomere length decreases to a critical threshold (5.8-10.5 kb)[56], the telomere maintenance mechanism becomes compromised, leading to chromosomal instability, DNA damage, and the consequent loss of genetic information. These changes result in reduced stemness and lifespan of stem cells[57]. Experimental studies have demonstrated a progressive decline in telomere length, which correlates with diminished proliferative capacity and the induction of replicative senescence in MSCs[58]. Furthermore, telomere shortening and DNA damage disrupt vascular homeostasis, contributing to thrombosis and AS[59].

Alterations in epigenetics cause senescence

Impaired DNA plays a crucial role in the senescence process. It can lead to phenotypic transformation of cells, which subsequently alters gene expression in vascular cells as well as the modifications to the composition and structure of ECM[60]. The recruitment of enzymes such as DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) and histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) contributes to the suppression of gene expression. Specifically, DNMT1 facilitates DNA methylation, while HDAC1 catalyzes histone deacetylation. Together, these processes bring about changes in the nucleosome structure[61]. BMSCs exhibit upregulated expression of nucleosome assembly protein 1-like 2 (NAP1L2). As a histone chaperone, NAP1L2 recruits silent information regulator transcript 1 (SIRT1) to deacetylate H3K14ac located on the promoters of osteogenic genes such as runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2), Sp7 transcription factor (sp7) and bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein (Bglap). This molecular mechanism promotes the senescence and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs[62,63].

In addition, epigenetics can also regulate gene expression by modifying the genome, thus exerting a long-term influence on the aging process of stem cells and promoting vascular aging. For example, this includes the methylation and acetylation of DNA and histones, as well as the regulation by non-coding RNAs. Research found that silencing the DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8 (DGCR8) gene in Human mesenchymal stromal cells (hMSC) raised methylation of the superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) gene promoter, which downregulated SOD2 expression, caused ROS accumulation and induced cellular senescence. Conversely, microRNA (miR)-29a-3p and miR-30c-5p can alleviate this by inhibiting DNA methyltransferase 3 alpha (DNMT3A), rescuing stem cell senescence. This finding confirms SOD2 promoter methylation is crucial in hMSC senescence, and the microRNA (miRNA)-epigenetic factor axis can precisely regulate this process[64]. In aging stem cells, increased histone deacetylase activity leads to the deacetylation of histones associated with the IL-10 gene, resulting in reduced IL-10 expression and enhanced inflammatory responses[65]. In addition, the highly expressed miR-34a in MSCs directly targets SIRT1 and Bcl-2, leading to reduced activity of SIRT1, an increase in cell apoptosis, and a decrease in the vascular endothelial repair capacity[66].

ECM remodeling destroys certain cell-cell adhesion

During the senescence process, ECM undergoes progressive remodeling, characterized by increased elastin degradation and collagen deposition[67]. Additionally, the increased stiffness of the ECM can induce stem cell senescence[68].

The secretory activity of aged MSCs is modified, and the ECM they produce can affect ECs. Specifically, this is manifested as an increase in the production of inflammatory chemokines, such as MCP-1 and growth-related oncogeneα, while the synthesis of the pro-angiogenic factor fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) is diminisheda[69]. Moreover, the levels of heparan sulfate proteoglycan in the cell lysate and versican in the conditioned medium are significantly decreased[70]. The key adhesion protein of the basement membrane, perlecan, is also affected, ultimately resulting in a decline in vascular regenerative capacity[71,72].

The hyaluronic acid (HA) in the ECM can bind to the CD44 receptor on the surface of MSCs and activate the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/serine/threonine kinase (PI3K-Akt) signaling pathway, thereby inhibiting the senescence process of MSCs. Conversely, a decrease in HA levels can promote the senescence of MSCs[73,74]. The hardening of the ECM downregulates histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3), leading to increased acetylation levels of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin, thereby activating phosphate and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN)-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1)/Parkin-mediated mitophagy[75]. The cellular communication network factor 1 protein generated by ECM fragmentation upregulates pro-senescence genes such as matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP-1) and IL-6 by activating the activator protein 1 transcription factor[76].

Mitochondrial dysfunction causes senescence

Mitochondrial fusion, which is triggered by elevated TGF-β1 and AMPK signaling pathway, results in cellular senescence of vascular progenitor cells (VPCs), characterized by enlarged cell size, elevated SA-β-gal activity, and increased expression of p53/p21. Consequently, VPCs exhibit impaired proliferation, weakened migration capacity, and reduced differentiation potential, ultimately exacerbating aortic aneurysms and vascular dysfunction in Marfan syndrome[77].

Mitochondrial dysfunction also induces ROS accumulation[77,78]. The study conducted by Lozhkin et al. in ref.[79] found that when the level of ROS increases, the activity of proteins related to mitochondrial fusion is suppressed. This, in turn, promotes mitochondrial fission, which further elevates the level of ROS and results in more severe mitochondrial dysfunction[79]. The HIF-1α-mediated metabolic reprogramming enhances pro-inflammatory cytokine release and disrupts mitochondrial dynamics (e.g., elongated morphology, decreased membrane potential), resulting in MSC dysfunction that aggravates AS[78]. When mitochondria are damaged, the leaked mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and ROS can directly interact with the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, serving as activators of the inflammasome. Alternatively, they can indirectly activate the NLRP3 inflammasome through the mtDNA-cyclic guanosine monophosphate-adenosine monophosphate synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (STING) (cGAS-STING) pathway[80,81], further damaging the mitochondria.

Degradation of mitochondrial autophagy is also a factor that cannot be overlooked. Impaired PINK1-parkin RING-between-RING E3 (RBR E3) ubiquitin protein ligase pathway-mediated mitophagy leads to the decline of EPC function and accelerates AS[82]. Study revealed that knocking out the cell-specific telomerase [telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT)] gene not only shortens telomeres through a telomere-dependent mechanism, leading to replicative cellular senescence, but also affects mitochondria through a non-telomere-dependent mechanism, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction and thus inducing cellular senescence[83,84].

The pathway of platelet production affects the probability of thrombus formation

In senescent HSCs, a chronic inflammatory microenvironment promotes myeloid differentiation bias and platelet production through NF-κB and Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathways. The NF-κB pathway directly inhibits the self-renewal capacity of HSCs and induces the excessive proliferation of megakaryocyte progenitors by upregulating inflammatory factors such as IL-6 and TNF-α. In contrast, the JAK/STAT pathway exacerbates the functional decline of HSCs and the abnormal production of platelets by regulating the suppressor of cytokine signaling family of proteins[85]. HSCs induce an inflammatory environment, which in turn leads to the production of Tom+ platelets. The abnormal mitochondrial function of Tom+ platelets enhances their sensitivity to thrombin and adenosine diphosphate, shortening the activation time by over 50%. Tom+ platelets release higher amounts of platelet factor 4, thromboxane A2, and P-selectin, which promote the recruitment of leukocytes and the deposition of fibrin. Tom+ platelets form a stable thrombus network by binding to neutrophil extracellular traps, thereby increasing the risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism[86]. As a result, the probability of thrombosis in individuals is significantly increased[87,88].

Sex-specific effects of stem cell aging

The specific impact of gender on stem cell aging is primarily manifested in two aspects: genetic material differences and hormonal differences. In terms of genetic material, the basal expression level of DNA repair genes in females (such as breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1)) is higher than that in males, which can reduce the accumulation of mutations in HSC and MSC, resulting in a significantly higher mutation rate of male DNA compared to that of females[89]. In terms of hormonal regulation, estrogen can induce the expression of antioxidant genes (such as SOD2 and catalase (CAT)), thereby reducing ROS levels[90]. On the one hand, estrogen can mitigate oxidative damage to MSCs. On the other hand, estrogen can upregulate the expression of TERT, enhance telomerase activity, and maintain the telomere length of HSCs and epidermal stem cells, thereby slowing down the physiological aging of stem cells[91].

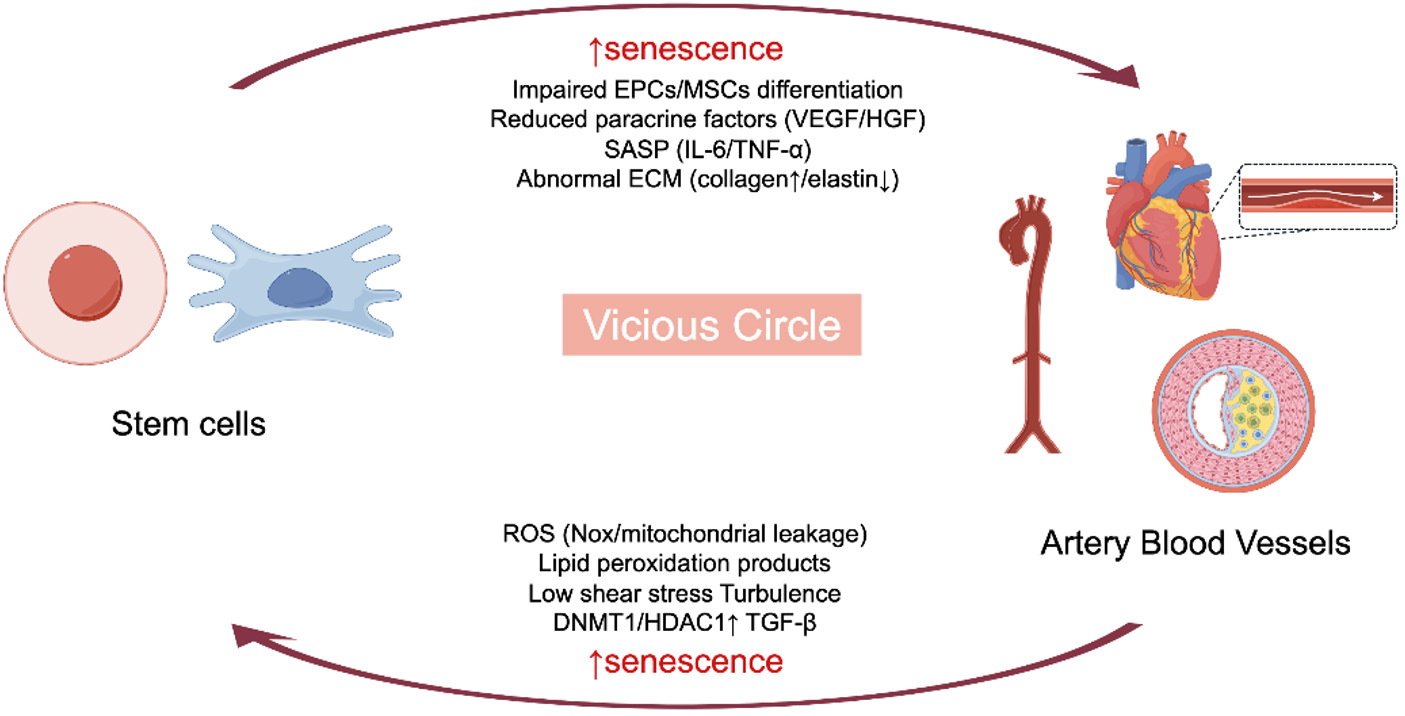

Overall, a vicious cycle involving oxidative stress, epigenetic alterations, and hemodynamic disturbances drives stem cell senescence and vascular dysfunction, ultimately contributing to pathological aging [Figure 2].

Figure 2. Schematic of the vicious circle linking stem cell senescence and vascular dysfunction. Stem cell senescence (impaired EPC/CSCs differentiation, SASP secretion, abnormal ECM) drives vascular pathologies (e.g., arterial changes); in turn, vascular-derived factors (ROS, lipid peroxidation products, etc.) promote stem cell senescence-β. EPC: Endothelial progenitor cell; MSC: mesenchymal stem cell; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; HGF: hepatocyte growth factor; SASP: senescence-associated secretory phenotype; ECM: extracellular matrix; ROS: reactive oxygen species; DNMT1: DNA methyltransferase 1; HDAC1: Histone deacetylase 1; TGF-β: transforming growth factor beta. (By Figdraw, ID: ISAIA3e550).

DIAGNOSTIC METHODS: IPSC-DERIVED IN VITRO MODELS

An overview of iPSCs

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are artificial stem cells induced from mature cells to a primitive state, able to differentiate into multiple cell lineages. Sources for inducing iPSCs include skin fibroblasts, nasal epithelial cells, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and cells in urine[92-101]. iPSCs are widely used to establish in vitro models that mimic the in vivo environment for disease modeling, diagnosis, drug testing, and related applications.

iPSC-based models in vitro

iPSC-microtissues-on-chip model

Microtissues-on-chip (VMToC) is a prevascularized and contractile three-dimensional (3D) cardiac microtissue model in vitro[102]. It combines iPSC-derived ECs and two other kinds of cardiac cells that are integrated into a microfluidic system with a fibrin hydrogel containing additional vascular cells[103,104]. This model can be applied in studying, such as endothelial dysfunction and microvascular obstruction, as well as vascular-cardiomyocyte crosstalk. Under bead perfusion and electrical pacing[103], vascular function and enhanced responses to pro-inflammatory stimuli (e.g., IL-1β), characterized by upregulation of cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 can be observed, enabling a more sensitive detection of vascular pathology[102]. For example, this platform can mimic post-ischemic microvascular dysfunction seen in myocardial infarction[102].

VMToC can also assess drug efficacy and immune cell trafficking via endothelial barrier permeability[103,104]. Theoretically, this model can be extended to individualized drug selection and disease mechanism detection for the specific gene mutation of iPSCs derived from individuals[102-104]. By testing drugs (e.g., L-NAME for NO inhibition) or inflammatory triggers (IL-1β), the model may assist in studying endothelial barrier dysfunction in conditions such as AS[102].

Since this model includes generating iPSC-ECs, it can also be employed in researching the interactions between ECs and VSMCs under physiological and pathological conditions, specifically, for the study of vascular physiology and disease mechanisms, such as congenital vascular diseases, coronary artery disease and AS[105].

iPSC-vessel-on-chip model

iPSC-ECs and iPSC-VSMCs form stable, functional microvascular networks in a microfluidic environment[106]. The iPSC-vessel-on-chip (VoC) model mimics EC-VSMC crosstalk in vessel walls, enabling studies of diseases caused by aberrant signaling between EC-VSMCs, including hypertension, AS, vascular calcification, and coronary artery disease[106]. Inhibition of the NOTCH signaling pathway (such as N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-L-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT) treatment) can simulate vascular degeneration, and the contractile dysfunction of iPSC-VSMCs (with decreased transgelin (SM22) expression) can reflect the pathological changes in hypertension, NOTCH-related developed vessel diseases and vascular sclerosis[106]. Patient-derived iPSCs retain genetic backgrounds, allowing modeling of genetic mutations, further endowing individualized diagnostic and therapeutic plans[106].

For drug examination, not only can endothelin 1-induced Ca2+ transients in VSMCs quantify drug effects on vascular contraction, but also drug responses can be simulated through DAPT disrupting NOTCH signaling[106]. A high-throughput drug screening can be imaged by open-source tools automating measurements of vessel density, branching points, VSMC morphology and SM22 intensity[106,107]. It can also be used to test the ability of resistance to anti-angiogenesis drugs of object vascular cells[107].

Furthermore, fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextran (70 kDa) perfusion could evaluate vascular leakage under drug or disease conditions. For example, iPSCs from reprogrammed fibroblasts from systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients, and differentiated ECs from iPSCs, are combined into an SSc-iPSC-EC model for their barrier function evaluation using a bioelectrical impedance cell platform[108].

THERAPIES FOR VESSELS DIRECTLY BASED ON STEM CELLS

Traditional therapies for vascular diseases related to vascular senescence include drugs and surgery. However, recent studies found that these approaches all have their own limitations and shortcomings. Side effects are inevitable in drug therapies, while recurrence and complications often occur after surgery[109]. Therefore, novel methods that depend on other forms are in urgent need.

Given that stem cells have the capacity to regenerate various cell types and repair tissues, their therapeutic potential has come into focus in recent years. Since the safety and reliability of stem cell therapies have been confirmed via animal model experiments and clinical studies[110], they shed a new light on prospect of stem cell-based therapies.

The therapeutic effects of MSCs' anti-senescence factors

The distinctions in treating pathological and physiological aging mainly reside in the sources and selection of stem cells, as well as the methods and approaches of treatment. Physiological aging is predominantly attributed to the decreased ability of cells to divide and proliferate, so cells with robust division capabilities, such as ESCs[111] and iPSCs, are often selected[112]. Additionally, some autologous stem cells, due to their relatively weaker immune rejection response and low acquisition difficulty, are also commonly used to treat physiological vascular aging. The treatment method often employs intravenous infusion of stem cells, enabling them to exert a systemic anti-aging effect. On the other hand, pathological aging is typically characterized by cellular lesions and metabolic disorders. For its treatment, MSCs with potent immune regulatory capabilities are prioritized[113]. The anti-inflammatory factors secreted by these cells can reduce inflammation and protect blood vessels. The treatment method usually varies depending on the location of the lesion, with stem cells being directly injected into the corresponding blood vessels to enable them to act directly on the affected area.

MSCs reinvigorate mitochondria and alleviate oxidative stress

Research showed that MSCs cocultured with lung microvascular ECs (MPMECs) increase the secretion of vascular growth factors (HGF) and VEGF messenger RNA (mRNA). MSCs are able to transfer healthy mitochondria stimulating the TCA cycle to MPMECs via tunneling nanotubes or dynamin-dependent clathrin-mediated endocytosis in mice models, decreasing ROS and inhibiting apoptosis, along with activating the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle in MPMECs[114]. Another study also found that transfer of mitochondria from MSCs to ECs via tunneling nanotubes is crucial for EC engraftment in ischemic tissues by triggering PINK1-Parkin-mediated mitophagy in preclinical in vivo models[115].

When cocultured and co-transplanted with ECs, MSCs show strong capability to stimulate the proliferation of ECs by activating the hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) signaling pathway through RNA hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha-antisense RNA 2 (HIF1A-AS2), as well as upregulating pro-angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), HIF1A, and platelet EC adhesion molecule 1[116].

MSCs alleviate inflammatory response

MSCs have shown immunosuppressive activity and reduced AS formation. After treatment with human amniotic MSCs (hAMSCs), the release of the pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α is reduced, while the release of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 is increased. Additionally, hAMSCs inhibit the phosphorylation of p65 and the release of inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B alpha (IκB-α), further reducing the inflammatory response[117]. Study proved that adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (ADMSCs) significantly reduced the expression of the inflammatory chemokine MCP-1, and also suppressed the expression of HIF-1α, thereby alleviating hypoxia-induced vascular injury and chronic inflammatory responses when applied in healing venous inflammation[118].

Umbilical cord MSC (UCMSC) transplantation is a potential therapeutic intervention for atherosclerotic vascular diseases. Integrin β3 (ITGB3) promotes the migration of various cell types. UCMSC transplantation with ITGB3 significantly reduces the inflammatory response by improving the dynamic balance of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines[119].

Additionally, using cytokines in conjunction with MSCs exerts synergistic effects. Growth differentiation factor 11 (GDF11) enhances endothelial differentiation and its role in the pro-angiogenic activity of MSCs through the TGF-β receptor/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)/eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E pathway[120]. Engineered UCMSCs expressing angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1) also promote vascular lumen formation and endothelial maturation by activating the Akt signaling pathway and inhibiting SRC proto-oncogene, non-receptor tyrosine kinase (Src) activity[121].

The anti-fibrotic effects of MSCs

Preconditioning with interferon γ and TNF-α significantly increases the content of anti-fibrotic proteins in MSC-derived cardiomyocytes (CM), including proteins that promote ECM degradation such as MMP-1and MMP-3, as well as proteins that inhibit the Wnt signaling pathway, such as dickkopf (DKK1) Wnt signaling pathway inhibitor 1. Additionally, analysis revealed that preconditioned MSC-CM can upregulate apoptosis and senescence pathways in myofibroblasts, thereby further enhancing the anti-fibrotic effect[122].

Delaying stem cell and vascular aging by modulating vascular shear stress

Appropriate hemodynamic stimulation can delay the senescence of MSCs by activating the antioxidant defense system[38]. Low levels of shear stress induce the migration of human MSCs through the stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1)/CXCR4 axis via the MAPK signaling pathway, enabling MSCs to home and migrate to damaged tissues[123]. This subsequently plays a role in repairing blood vessels in clinical applications.

iPSC involved therapies

Direct differentiation of iPSCs into cells constituting vascular wall

VSMCs, pericytes, and ECs have all been reported to originate from iPSCs in vitro[98,124,125]. The addition of VEGFs induces the differentiation of iPSCs into venous ECs (CD31+/CXCR4-). When co-cultured with supporting pericytes, these ECs further promote the differentiation of pericytes into VSMCs. If adding 8-bromoadenosine 3',5'-cyclic monophosphate, iPSCs are inclined to transform into arterial ECs (CD31+/CXCR4+)[126]. Serum-free protocols containing fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), VEGFA, 4-[4-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-5-(2-pyridinyl)-1H-imidazol-2-yl]benzamide2, resveratrol and L690 (“five factor”) can effectively induce iPSCs to differentiate into arterial ECs, through VEGF, Wnt, and NOTCH signaling, among other pathways[96]. iPSCs can also differentiate into HSCs by recapitulating embryonic developmental processes in vitro[127], potentially alleviating vascular senescence if the homing capability of HSCs is ameliorated.

Based on compelling preclinical evidence from both murine and non-human primate (NHP) models, the combined transplantation of isogenic iPSC-derived CMs and ECs emerges as a promising regenerative strategy for ischemic cardiomyopathy. In a mouse model of myocardial infarction, co-transplantation of iPSC-CMs and iPSC-ECs significantly improved cardiac function, enhanced graft vascularization, and reduced infarct size. Critically, these therapeutic benefits were successfully translated to a NHP model of ischemic-reperfusion injury, where the combined treatment robustly augmented graft size and vascular density. This comprehensive small-to-large animal validation underscores the synergistic potential of this multicellular therapeutic approach and provides a robust preclinical foundation for its clinical application[128].

Reprogramming MSCs and other stem cells for regeneration

By using small molecules to alter the epigenetic state of cells, we can ultimately achieve cell fate reprogramming and generate chemically iPSCs (CiPSCs). We can reprogram the MSCs undergoing endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in AS, reverting them back into non-inflammatory blood cells and vascular ECs[129].

THERAPIES BASED ON SUBSTANCES DERIVED FROM STEM CELLS (PARACRINE EFFECTS)

Direct paracrine

Stem cells exert beneficial effects largely owing to releasing growth factors, cytokines, exosomes, and other micro-vesicles, which are collectively referred to as “paracrine effects”.

The therapeutic effects of paracrine regulate immune responses

SSc is an autoimmune disease characterized by vascular involvement, dysregulation of innate and adaptive immune responses, and progressive fibrosis. MSCs can secrete factors such as VEGF and FGF-2 to promote vascular repair. They also inhibit the overactivation of immune cells through indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and prostaglandin E2, modulate the balance of regulatory T cells and T helper 17 cells, and suppress the proliferation of fibroblasts and collagen synthesis[130].

Under physiological conditions, vascular ECs play a role in reducing the risk of contributing to the reduction of[131]. Additionally, the apoptosis of MSCs can also promote vascular repair. Research has indicated that transplanted MSCs undergo apoptotic fate within 24 h in vivo[132]. Nevertheless, the short-term survival of MSCs does not affect their long-term therapeutic efficacy. An increasing number of studies have shown that transplanted apoptotic MSCs (ApoMSCs) exert therapeutic effects comparable to or even superior to those of live MSCs exhibit similar or even better therapeutic effects compared to live MSCs. During the apoptosis of MSCs, MSC-derived apoptotic bodies (MSC-ApoEVs) are formed. Apoptosis of MSCs generates MSC-ApoEVs. Once phagocytosed by vascular ECs, the MSC-ApoEVs can upregulate the expression of lysosomal membrane proteins, activate lysosomal function, and mediate the translocation of transcription factor EB (TFEB) into the nucleus, thereby enhancing the autophagic activity and angiogenic capacity of ECs. ECs, which, after being engulfed by vascular ECs, increase the expression of lysosomal membrane proteins, activate lysosomal function, and mediate the translocation of TFEB to the nucleus to enhance autophagy in ECs and boost their angiogenic capacity[133,134].

The therapeutic effects of paracrine under pathological situations

(1) The paracrine effects of MSCs attenuate oxidative stress

In vitro supplementation of secreted proteins from MSCs derived from bone, umbilical cord and adipose all promote the proliferation of ECs via VEGF/feline McDonough sarcoma (fms)-related receptor tyrosine kinase pathway, as well as bettering ECM remodeling via TGF-β pathway under oxidative stress (high glucose environment), with UCMSCs demonstrating the premium capacity[135].

UCMSCs have the ability to ameliorate blood-glucose conditions as well as preserve vascular endothelium through paracrine, both in vivo and in vitro, of experimental mice, where MAPK/ERK signaling mediated its paracrine molecular mechanism[136]. A wide range of growth factors including HGF, VEGF, as well as anti-inflammatory factors, are secreted to incentivize cell propagation, tissue restoration and intercellular interaction[137]. In one study, UCMSCs secreted pro-angiogenic factors (VEGF, HGF, epidermal growth factor, and basic fibroblast growth factor) that enhanced endothelial tube formation and neovascularization in mice, but did not directly differentiate into ECs, indicating angiogenesis was mediated primarily via paracrine signaling[138].

(2) The paracrine effects of MSCs alleviate inflammatory response

The hyperglycemia caused by diabetes can lead to damage and apoptosis of vascular ECs due to oxidative stress and inflammatory responses. MSCs can reverse the abnormal phosphorylation of ERK through paracrine effects. They can also reduce the overexpression of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase-interacting serine/threonine kinase 2, erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 3, MYC proto-oncogene, basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor, and dual specificity phosphatase 5 in the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway, thereby protecting vascular ECs from the damage caused by diabetes[136].

(3) Different sourced MSCs present diverged paracrine patterns

Of note, a recent head-to-head comparative study systematically profiled BMSCs, ADMSCs, UCMSCs and iPSC-derived MSCs (iMSCs) under both resting and inflammatory licensed conditions. MSC source emerged as a major determinant of secretome composition: iMSCs and UCMSCs exhibited enhanced proliferative and pro-angiogenic potential, suggesting they appear better suited for pro-regenerative applications, including vascular repair. In contrast, adult tissue-derived MSCs (BMSCs and ADMSCs), which secrete profiles dominated by ECM and homeostatic factors, may be more appropriate for modulating tissue structure and fibrosis. Critically, while all MSCs acquired immunomodulatory capacity upon licensing, iMSCs demonstrated superior potency in suppressing T-cell proliferation, highlighting their potential preference for managing autoimmune and inflammatory conditions[139].

Long-term therapeutic effect of MSCs

Long-term efficacy of MSC therapy is evidenced by its continuous promotion of angiogenesis and functional recovery. In chronic cerebral ischemia, local MSC transplantation combined with encephalo-myo-synangiosis enhances long-term (30-day) collateral vessel formation, blood flow, and cognitive function. MSCs exert their effects via paracrine secretion, upregulating pro-angiogenic factors such as matrix metalloproteinase-3/9 (MMP-3/9), insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-2/3 (IGFBP-2/3), VEGF, and TGF-α, along with related miRNAs, without differentiating into vascular cells[140]. Similarly, in a mouse model of ischemia-reperfusion injury, local MSC delivery via a HA hydrogel under the renal capsule demonstrated sustained therapeutic efficacy over one month (28 days)[141]. A single intravenous injection of UCMSCs either at 8 weeks (early-stage) or 16 weeks (late-stage) provided sustained renal protection in mice with diabetes. Evaluations at 10 and 18 weeks post-diabetes induction demonstrated a persistent attenuation of glomerular basement membrane thickening, mesangial expansion, and interstitial fibrosis[142]. These findings confirm that MSC therapy confers durable microvascular and structural improvements in diabetic nephropathy, with benefits maintained through later disease stages.

Secreted EVs and exosomes

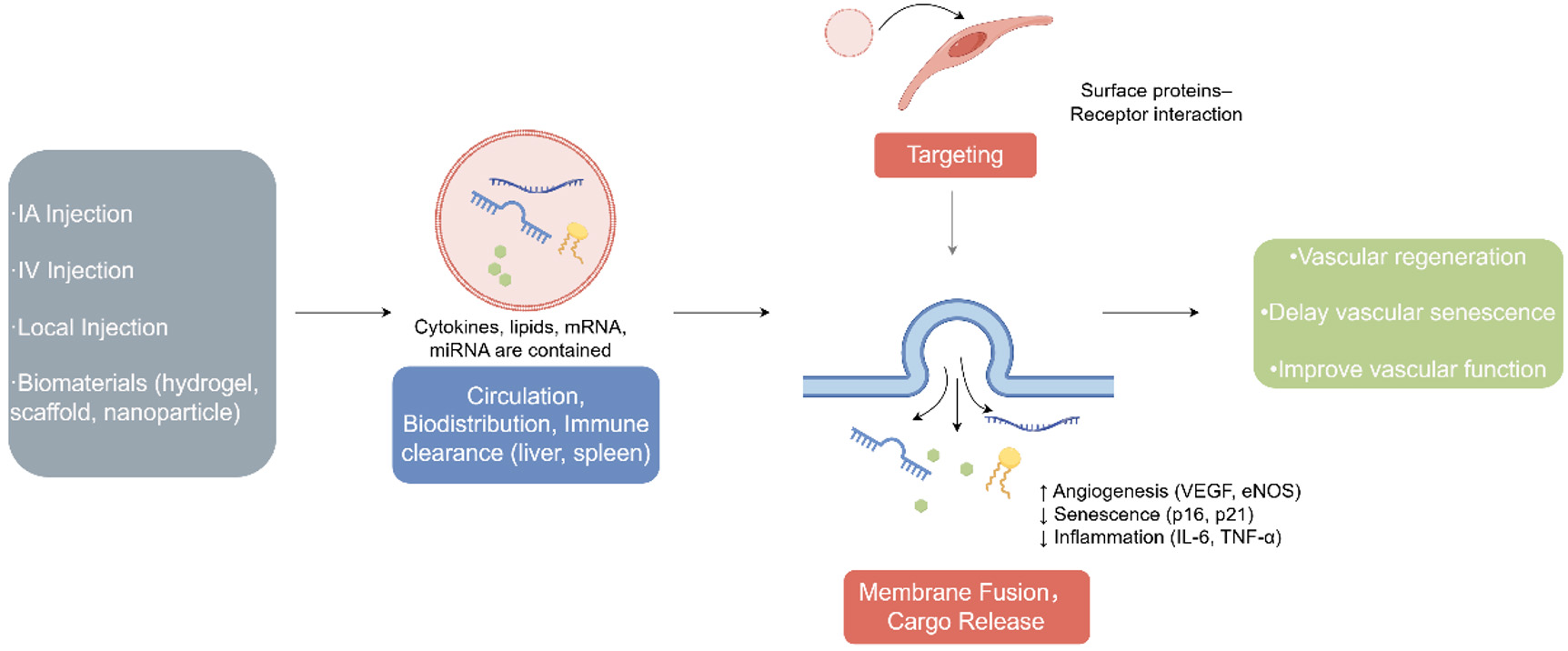

EVs are crucial for intercellular modulation and message transmission, encompassing cellular components including cytokines, growth factors, signaling lipids, mRNA, and regulatory microRNA[143]. Exosomes are natural nanovesicles for intercellular communication and biomaterial transport. Therapies based on introducing EVs and exosomes are becoming increasingly promising[144]. Compared to cell therapies, EVs have no tumor formation risk and more predictable activities[145,146] [Figure 3].

Figure 3. Mechanism of extracellular vesicle (EV) delivery in vascular rejuvenation. EVs can be administered via intravenous, intra-arterial, or local injection, as well as through biomaterial-assisted systems such as hydrogels or scaffolds. Following administration, EVs enter the circulation and undergo biodistribution, with partial clearance by the liver and spleen. Surface proteins mediate selective binding to vascular ECs, enabling targeted delivery to sites of injury or dysfunction. Uptake occurs mainly through endocytosis or membrane fusion, after which EVs release their bioactive cargos (miRNAs, proteins, lipids) into recipient cells. These cargos activate pro-angiogenic signaling pathways, suppress senescence-associated markers, and attenuate inflammation, ultimately promoting vascular repair, delaying vascular aging, and restoring vascular function. (By Figdraw, ID: IYIAT1abbf).

Stem cell-derived EVs promote cardiovascular repair through integrated mechanisms. They trigger angiogenesis by delivering VEGF, which activates VEGFR1/VEGFR2 signaling, and miRNAs such as miR-210-3p, which function downstream of HIF-1α. EVs mitigate apoptosis by transferring miR-22, which targets methyl-cytosine-phosphate-guanine (cpg) binding protein 2, and miR-214-3p, which modulates the Bcl-2/Bcl-2-associated x protein axis. Furthermore, EVs induce immunomodulation via miRNAs such as miR-146a and miR-21, polarizing macrophages toward an M2 phenotype, and facilitate metabolic reprogramming through the transfer of miR-155 and miR-210, thereby influencing glycolytic and oxidative phosphorylation pathways. Collectively, these actions underscore the multifaceted therapeutic potential of EVs in cardiac regeneration[147].

EVs attenuate ROS, DNA damage and SASP marker

In vitro, mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs) reduce senescent biomarkers, ROS, DNA damage and SASP induced by IL-1α, IL-6, and IL-8, both of which are associated with the senescence vascular ECs phenotype induced by oxidative stress[144] [Figure 3]. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) derived from hypoxia-conditioned MSCs are enriched with parkinsonism-associated deglycase, reducing mitochondrial oxidative stress and inhibiting Ang II-mediated AT1R activation, thereby ameliorating[148]. In a controlled experiment, models of pulmonary arterial hypertension incorporating additional MSC-EV injection also confirmed that MSC-EVs improve vascular function by shifting the balance from the ACE-Ang-II-AT1R axis toward the ACE2-Ang-(1-7)-Mas axis[149]. EVs also exhibit anti-senescence ability via miR146a/Src proto-oncogene, non-receptor tyrosine kinase pathway, and enhance neovascularization while reducing senescent ECs in natural aging and type-2 diabetes mouse models[144]. MSC-EVs restore mitochondrial function by reconstructing and strengthening the stability of the mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) protein and TFAM- mtDNA complex, reversing mtDNA deletion and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation[150]. Therefore, MSC-EVs can be applied to reverse the senescence mechanism of stem cells and the vascular wall caused by ROS and other factors [Figure 3].

MSC-EVs: targeted repair for aortic aneurysms

Surface-functionalized MSC-EVs exhibit a competent ability in vascular elastic matrix regenerative repair. By conjugating cathepsin K (CatK)-binding peptides to the surface of EVs, the uptake of which in cultured VSMCs and ex vivo injured vessel walls is significantly enhanced. The modified EVs exhibited positive effects in inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2) and promoting lysyl oxidase expression[151], offering a novel approach for targeted abdominal aortic aneurysm therapy.

Enhanced EVs promote angiogenesis through reversing multiple senescent mechanisms

Stem cell-derived EVs treated with chemical compounds show better effects. Silicate ions incorporated with EPC-derived EVs activate EPCs to produce high-yield and highly biologically active EVs (CS-EPC-EVs). This process upregulates heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 and neutral sphingomyelinase 2 expression, selectively sorts microRNA 126a-3p into EVs, which inhibits regulator of G-protein signaling 16, activates the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis and its downstream PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway, promotes angiogenesis in human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) and EPC homing, and improves vascularization and cardiac repair[152]. EVs derived from empagliflozin-pretreated MSCs markedly increased the number of CD31+ cells in the infarct border zone, thereby improving myocardial blood supply through enhanced angiogenesis[153].

MSC-EVs transmit functional mitochondria

MSC-EVs contain functional mitochondria that are internalized by lung epithelial and ECs. Then, these mitochondria integrate into the host mitochondrial networks to restore oxidative phosphorylation. MSC-EVs suppress the overproduction of mitochondrial ROS, downregulate pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-8, TNF-α), and reduce vascular injury markers in lipopolysaccharide-injured mice[154], which provides insights into the treatment of ischemia. Additionally, small EVs derived from nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2-overexpressing hAMSCs protect against lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced acute lung injury by inhibiting nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor (NLR) family pyrin domain-containing 3[155].

Exosomes downregulate senescence-associated proteins and promote cell cycle

Exosomes isolated from iPSCs demonstrate angiogenesis capacity in both young and naturally aged mice models[112]. In old mouse models treated with iPSC-derived exosomes, neovascularization surrounding the aortic ring is observed, along with a decrease in p16 and p53 levels[112]. Exosomes derived from UCMSCs act as the carrier of miR-675. miR-675 exerts its effect by targeting and inhibiting the expression of TGF-β1, and p21, thereby promoting cell proliferation and blood perfusion in ischemic hindlimbs[156] [Figure 3]. Furthermore, exosomes derived from MSCs sourced from endometrium, bone marrow and adipose tissue encapsulate miR-21. This miR-21 activates the PTEN/Akt pathway, upregulating VEGF expression and stimulating angiogenesis[143].

Collectively, emerging evidence underscores the significant therapeutic potential of MSC-derived exosomes in mitigating cerebral ischemic injury, with microRNA-486 emerging as a key mediator. Studies including rodent middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) in vivo and oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation (OGD/R) in vitro demonstrate that exosomal miR-486 directly promotes angiogenesis in EC by targeting PTEN[157]. Concurrently, it attenuates neuronal injury by enhancing cell viability, suppressing apoptosis, and reducing oxidative stress in neural cells[158].

Exosomes work against oxidative stress and apoptosis

Emerging evidence highlights the therapeutic role of ADMSC exosomes in limb ischemia through distinct yet complementary mechanisms. In diabetic ischemic models, ADMSC-derived exosomes have been shown to deliver miR-125b-5p, which directly targets alkaline ceramidase 2 (ACER2) and activates the AMPK pathway, thereby alleviating oxidative stress and apoptosis in skeletal muscle cells and promoting angiogenesis[159]. Building on these mechanistic understandings, further studies in acute non-diabetic hindlimb ischemia demonstrate that ADMSC exosomes enhance neovascularization, increase capillary density, and improve hemodynamic recovery. As a result, significant functional restoration and tissue necrosis are reduced within 28 days[160]. Collectively, these findings confirm the broad regenerative capacity of ADMSC exosomes in preclinical limb ischemia models.

Totally, stem cell therapy uses a range of strategies, including iPSC differentiation, MSC-mediated mitochondrial transfer, anti-inflammatory modulation, anti-fibrotic effects, and shear stress response. These mechanisms collectively promote vascular repair and regeneration through processes such as oxidative stress reduction, cytokine balance, and enhanced cellular homing, as summarized in Table 1.

Methods, mechanisms and effects of stem cell therapy in vascular repair and regeneration

| Therapy category | Specific method | Mechanistic details/Observation basis | Observed effects | References | Key limitations |

| iPSC technologies | Directed differentiation | VEGF-induced venous ECs; "five-factor" arterial EC protocol | Generates functional vascular cells (ECs, VSMCs) | [113,115] | • Functional immaturity: iPSC-ECs lack mature Weibel-Palade bodies and show immature Ca2+ handling • Tumorigenicity Risk: Genomic instability from reprogramming and residual undifferentiated cells |

| MSC direct applications | Mitochondrial transfer | Transfer healthy mitochondria via tunneling nanotubes; activate TCA cycle; upregulate VEGF/HGF | Reduces oxidative stress and apoptosis; enhances EC proliferation | [101,102] | • Source-Dependent Heterogeneity: Efficacy varies with MSC source (e.g., UC-MSC vs. AD-MSC) • Poor Cell Retention: Rapid clearance after systemic delivery • Incomplete Mechanism Understanding: Precise immunomodulatory actions in the lesion microenvironment are not fully known |

| MSC direct applications | Anti-inflammatory modulation | Reduce TNF-α, IL-8; inhibit MCP-1; ITGB3 improves cytokine balance | Attenuates atherosclerosis and chronic inflammation | [104-106] | None specified |

| MSC direct applications | Anti-fibrotic action | Upregulate MMP-1/3; inhibit Wnt pathway (DKK1); induce myofibroblast apoptosis | Decreases vascular fibrosis | [109] | None specified |

| MSC direct applications | Shear stress response | Activate SDF-1/CXCR4 axis; enhance antioxidant defenses | Improves MSC homing and delays aging | [34,110] | None specified |

| Therapies based on paracrine effects | MSC conditioned medium | Acts via VEGF/FLT-1 and TGF-β pathways under oxidative stress | Promotes EC proliferation and ECM remodeling | [122] | • Variable Potency: Paracrine capacity is affected by donor factors and culture conditions (e.g., hypoxia, high glucose) |

| Therapies based on paracrine effects | Apoptotic MSC bodies (ApoEVs) | Upregulate lysosomal proteins and activate TFEB in ECs after phagocytosis, enhancing autophagy | Boosts angiogenic capacity of ECs | [120,121] | None specified |

| Therapies based on EVs/Exosomes | MSC-EVs (General) | Deliver miR-146a to inhibit Src; restore TFAM protein stability to improve mitochondrial function | Reduces senescence markers; enhances neovascularization; improves vascular function | [131,137] | • Manufacturing Hurdles: Lack of standardized isolation methods leads to heterogeneous products • Delivery Inefficiency: Low targeting specificity and rapid systemic clearance • Drug Loading Challenges: Loading strategies may compromise EV membrane integrity |

| Therapies based on EVs/Exosomes | Targeted MSC-EVs | Surface functionalization with Cathepsin K-binding peptide (CKBP) enhances uptake in VSMCs | Downregulates MMP-2, upregulates LOX, and promotes elastic matrix repair for aneurysms | [138,168] | None specified |

| Therapies based on EVs/Exosomes | Enhanced EPC-EVs | Silicate-activated EPCs produce CS-EPC-EVs enriched with miR-126a-3p, inhibiting RGS16 and activating SDF-1/CXCR4/PI3K/Akt/eNOS axis | Promotes angiogenesis in HUVECs and EPC homing, improves cardiac repair | [139] | None specified |

| Therapies based on EVs/Exosomes | Drug-pretreated MSC-EVs | Empagliflozin-pretreated MSC-sEVs | Increases CD31+ cells in the infarct border zone, improving blood supply | [140] | None specified |

| Exosomes (iPSC/MSC) | Exosomes (iPSC/MSC) | iPSC-Exos decrease p16/p53; UCMSC-Exos deliver miR-675 inhibiting TGF-β1/p21; MSC-Exos deliver miR-21 activating PTEN/Akt | Promotes angiogenesis in aged models; promotes cell proliferation and blood perfusion; upregulates VEGF | [99,130,143] | None specified |

Critical quality attributes (CQAs) such as particle size, surface markers, and RNA cargo are essential for ensuring product standardization[161].

PRACTICAL CLINICAL APPLICATION METHODS

Delivery

Practical delivery methods applied in clinical treatments mainly include systemic delivery (intravenous injection, arterial injection) and topical administration [Figure 3]. Systemic delivery refers to administering stem cells through blood vessels, which is applicable for chronic and extensive vascular healing. Topical administration requires direct perivascular injection, often being utilized in localized angiogenesis.

Systemic delivery

As one of the most prevalent methods for drug delivery, intravenous/intra-arterial (IA/IV) injection has drawn public attention, particularly in the context of stem cell therapy delivery. IV infusion is characterized by non-invasive features and is easy to operate clinically[162]. Clinical trials have verified that IV injection of UCMSCs significantly alleviates chronic limb ischemia. Moreover, it exerts systemic anti-inflammatory and paracrine effects, contributing to the improvement of micro-circulation[163]. Furthermore, intravenously transplanted UCMSCs or ADMSCs could accelerate wound healing by increasing CD31+ vascular density, which improves local blood supply. They also regulate the expression of inflammatory factors (such as IL-1α and TNF-α) thereby reducing inflammation and promoting angiogenesis[164,165]. Research found that UCMSCs can be effectively delivered via femoral vein injection, homing to ulcer sites within 24 h, highlighting the significant efficiency of intravenous delivery for stem cell transplantation in the healing of ischemia[164].

However, evidence also indicates that the therapeutic effects of MSCs are restricted due to their rapid elution from the disease focus within a short period when directly injected into blood vessels[118]. Meanwhile, MSCs and EVs need to traverse the entire circulatory pathway before reaching the targeted site[166], which is suitable for systemic therapeutic objectives, but not for precise localized curation. In a study focusing on the comparison of the efficiency and effectiveness of IV and IA delivery of MSCs for treating diabetes, it was found that when applying IA, the injection requires precise artery blockage to confirm the precision of local delivery in rat models[167]. It was also revealed that substances delivered via IA and IV routes largely accumulated in spleen, liver[167] and lungs, where a large number of macrophages reside [Figure 3]. This may decrease the efficacy and is not cost-effective. Quantitative positron emission tomography tracking demonstrated that the in vivo distribution of systemically administered MSCs is more effectively regulated by cell size than adhesion capacity. A 34.6% reduction in cell size achieved through 3D spheroid culture significantly decreased pulmonary retention and promoted the survival and the homing rate to the liver[168].

In addition, for some intravenous delivery, inserted catheters are usually applied. Thus, the difficulties in piercement and catheter insertion cannot be ignored, especially in elderly patients with thinner vessels and stiffer vascular walls.

Topical administration

Topical administration, also known as local injection, is typically employed for partial precise treatment, such as perivascular injection and intramural injection, with the aim of delivering stem cells and substances to vessel walls. Local injection of BMSCs can improve local ischemia and promote microvascular angiogenesis through the secretion of VEGF[169]. A clinical trial found that when applying topical administration, where UCMSCs were injected subcutaneously around the ulcer and into its base, over 95% of the ulcer area had healed in all patients, suggesting its application potential in treating ischemia and microvascular circulation[163]. Recent research has shown that by applying ultrasound technology, vascular stem cells can be precisely targeted to specific vessel wall and further ameliorate the aortic aneurysm formation[170]. In addition, topical administration exhibits a relatively high retention rate of stem cells. One study showed that MSCs injected in the adventitia lasted for over 3 weeks, indicating sustained local therapeutic activity[118]. Stem cells can be located in the perivascular space, and may replace damaged pericytes[171].

However, topical administration faces challenges, including rapid cell clearance, risk of immune rejection, and high demands for precise operation[171]. Besides, imported supportive technologies, such as ultrasound-guided, require special instruments and techniques[170].

Medium for cargos (stem cells & exosomes)

Biopolymeric polymetric scaffolds, especially hydrogels, are the most common wraps chosen for stem cell and paracrine factors delivery. Meanwhile, auto-membrane modification is also increasingly promising [Figure 3].

Bioresorbable polymeric scaffold

Fibrous scaffolds composed of bioresorbable synthetic polymers can act as an ideal bioresorbable 3D matrix[166,172]. These scaffolds serve as a “carriage” transporting the MSCs and protecting them, since the polymers are relatively inert[166], highlighting an advantage over injection. Commonly used materials include poly-L-lactide, polyglycolic acid, and poly lactic-co-glycolic acid[173]. Research also implies that matrices integrating electrospun scaffolds and biological polymers exhibit beneficial effects[166,172]. Additionally, the addition of gold aids in precisely locating arteriovenous fistulas[174]. Compared to injection, MSCs encapsulated in scaffolds persist at the pathological site for a longer duration[116,175]. Moreover, the integration of MSCs with scaffolds enhances their adhesion, propagation and paracrine secretion via the stimulation of MAPK, PI3K/Akt, focal adhesion kinase/Src, yes-associated protein/transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif, Wnt/β-catenin and other pathways[166,176-178].

Regarding exosomes and EVs, silk fibroin hydrogel can extend their half-life while ensuring sustained release in vivo[156]. Gelatin methacryloyl-polyethylene glycol (GelMA-PEG) microspheres are advisable for encapsulating EVs, as research has confirmed that CS-EPC-EVs encapsulated by GelMA-PEG microspheres were continuously and sustainably released for 21 days in vivo[152]. Hydrogel is often derived from the decellularized matrix of porcine myocardium, which is economical, biocompatible, degradable, thermosensitive, capable of mimicking the natural skin environment, and supportive of cell growth[179]. ECM hydrogels provide physical support and sustained-release platforms, promoting angiogenesis by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway through miRNAs (such as miR-126-3p)[179]. Hydrogels coupled with inorganic substances, such as MnO2, can promote macrophage type 2 polarization and accelerate angiogenesis[180]. Furthermore, 3D hydrogels can increase the secretion of immunosuppressive factors[181]. Moreover, fibrin glue (FG) is also an effective scaffold in clinical practice. Using FG as a cell delivery vehicle can effectively enhance the retention time of UCMSCs[121].

Surface modification of exosomes and EVs

Another common approach for delivering exosomes and EVs is the modification of their surfaces. Surface modification enhances exosomes' functionality for targeted drug delivery, enhancing the delivery efficiency and the therapeutic effect in specific areas. Specific exosomal membrane proteins such as tetraspanins (CD63, CD81, CD9), lactadherin (LA), lysosome-associated membrane protein-2b (Lamp-2b), and glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) are commonly used as modification molecules. While genetic engineering, covalent modification and non-covalent modification of exosomes are also utilized in exosome modifications[182].

Targeted EVs functionalized with a CatK-binding peptide (CKBP) via copper-free click chemistry demonstrate enhanced site-specific delivery and retention in aneurysmal tissues. These modified EVs exhibit significantly improved binding and cellular uptake in cytokine-stimulated VSMCs and elastase-injured arterial explants, confirming effective targeting to CatK-overexpressing microenvironment[151].

Current chemical strategies for modifying EVs frequently encounter challenges in balancing functionalization efficiency with structural preservation. By introducing the suicide nucleotide analog peptide tag for stable modular binding, along with the N-terminal syntenin-derived sorting domain, streptomyces phospholipase D and maleimide-functionalized primary alcohol to boost the expression of chimeric adaptor proteins on EVs[183,184], the functionalization efficiency is consolidated while maintaining the integrity of EVs, which can even last for months.

DISCUSSION

CVDs remain a leading global health concern, with rising incidence and mortality rates, particularly due to vascular aging. Their progression is influenced by various factors, including physiological aging (telomere shortening) and pathological mechanisms (oxidative stress, inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, epigenetic alterations and others). Stem cells, particularly MSCs and iPSCs, have emerged as promising therapeutic tools due to their regenerative, anti-inflammatory, and angiogenic properties. These cells can differentiate into vascular cell types (such as ECs, smooth muscle cells) and secrete paracrine factors that promote tissue repair.

Recent advances in stem cell-based therapies highlight their potential in mitigating vascular aging. MSCs can rejuvenate damaged tissues by transferring healthy mitochondria, reducing oxidative stress, and modulating inflammatory responses. Additionally, iPSC-derived models (VMToC and VoC systems) provide valuable platforms for disease modeling, drug screening, and personalized medicine. EVs and exosomes derived from stem cells further enhance therapeutic efficacy by delivering bioactive molecules that improve vascular function, reduce aging, and promote angiogenesis.

Delivery methods, including systemic (IA/IV) and localized perivascular administration, are being optimized to enhance stem cell retention and therapeutic precision. Despite challenges such as rapid cell clearance and immune rejection, innovations in biomaterials (e.g., hydrogels, polymeric scaffolds) and surface modifications of EVs are improving treatment outcomes.

In conclusion, stem cell-based therapies represent a transformative approach to combating vascular aging and CVDs. Future research should focus on refining delivery techniques, enhancing stem cell survival, and translating preclinical findings into clinical applications to improve cardiovascular health globally. However, recent research demonstrates shortcomings.

Limitations of iPSC-derived cells

For one thing, the differentiated cells derived from iPSCs show limitations. iPSC-ECs exhibit a higher sensitivity to sunitinib compared to HUVECs, with a half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 20 nM for iPSC-ECs and 66 nM for HUVECs. This may reflect the differences in metabolism or signaling pathways between iPSC-EC and primary HUVESCs[107]. For another, in vitro models cannot completely mimic the environment in vivo[102]. The gravity-driven flow in in vitro models lacks physiological shear stress, and the absence of pericytes/immune cells limits physiological relevance. iPSC-VSMCs show incomplete maturation, and long-term cultures exhibit network degradation. Disease modeling remains limited to acute interventions, and image analysis lacks standardization[105,106]. Most therapies and in vitro models require refinement in detail. For example, in some iPSC-derived VoC models, the permeability of the vascular wall needs to be curtailed by drugs[185]. On the other hand, in vitro models can mimic certain vascular functions; they face challenges in replicating complex mechanical forces in vitro, such as shear stress and multi-organ interactions[186].

Regarding the iPSC therapies, iPSC-VSMCs display few Ca2+ peaks characterized by longer durations and slower decay kinetics, which may be attributed to immature endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ handling mechanisms and ion channel regulation[187]. Although the expression of CD34, CXCR4, VEGFR2, and VEGFR3 is higher, some arterial markers such as NOTCH1 and NOTCH4 are found to be lower than those in HUVECs[125], suggesting an improvement is still needed in iPSC-ECs. Meanwhile, iPSC-ECs cannot function as normal ECs because they fail to form proper vWF and Weibel-Palade bodies, which are essential for angiogenesis, primary and secondary homeostasis[188].

The limitations of the current vessel-on-chip model

Although the VoC model provides a promising platform for simulating vascular environments in vitro, enabling diagnostic modeling and drug testing outside the living organism, it still exhibits several limitations.

A primary challenge is the frequent absence of essential cell types, such as VSMCs and immune cells, and the use of ill-defined ECM components such as Matrigel or fibrinogen, which exhibit high batch-to-batch variability and fail to recapitulate a healthy vascular microenvironment[189]. Furthermore, these systems often have difficulty replicating the multi-scale geometry of human vasculature and maintaining physiological shear stresses across all vessel dimensions. The absence of a systemic circulation limits the ability to model the systemic immune and inflammatory responses that are crucial for many vascular diseases[190]. Additionally, transient shear gradients on endothelial mechanosensitive pathways (such as Krüppel-like factor 2 (KLF2), eNOS, and NOTCH), potentially leading to an underestimation or misrepresentation of aging-related alterations in mechanotransduction[191]. The use of organ-specific ECs remains scarce, which compromises model fidelity. Furthermore, the common use of undeveloped material (e.g., polydimethylsiloxane) confounds drug screening efforts, necessitating a shift to alternative, low-absorbance materials[192,193]. The practical utility for studying chronic diseases is also hindered by limited culture longevity, typically not exceeding 14-21 days; therefore, there is a need to validate the structural and functional stability of VoC systems over extended periods[192,193].

Clinical application of stem cell therapy in vascular diseases

Therapeutic potential of clinical stem cell therapy in vascular diseases

Several clinical trials have investigated the use of MSCs for the treatment of different types of CVDs. One study reported that intravenous administration of autologous ADMSCs improved cardiac function in a patient with acute ischemic cardiomyopathy[113]. Two allogeneic BMSC-based therapies have demonstrated efficacy in treating critical limb ischemia (CLI) in clinical trials. A Phase III trial evaluating Stempeucel® showed statistically significant improvements in ulcer healing, ankle-brachial pressure index, and ankle systolic pressure in patients over a 12-month follow-up[194]. Additionally, phase I-IV studies on REGENACIP® revealed vascular benefits in patients with chronic CLI. The therapy was well-tolerated and induced significant improvements, indicating REGENACIP® as a safe and effective treatment that promotes angiogenesis and vascular regeneration[195].

To sum up, stem cell therapy for vascular diseases demonstrates superior therapeutic efficacy compared to traditional approaches. It facilitates vascular and tissue regeneration and modulates pathological processes through multi-target mechanisms. In contrast, conventional therapies primarily offer symptomatic relief and target single pathways. Furthermore, stem cell therapy exhibits enhanced safety and tolerability, with lower rates of immune rejection and fewer, milder adverse effects. Traditional treatments, by comparison, are associated with a broader range of potential adverse reactions. Additionally, stem cell therapy is minimally invasive, involves fewer complex procedures, results in reduced trauma, and supports faster recovery, thereby minimizing the need for extended hospitalization or rehabilitation[113,196,197].

Unresolved challenges in the clinical translation of stem cell therapy for vascular diseases

Despite the promising therapeutic potential of stem cell-derived approaches, several translational challenges remain. Key hurdles include ensuring the scalability and standardized production of these biologics, optimizing dosing regimens, and conducting comprehensive long-term safety evaluations[198].

Immune rejection remains a major concern in stem cell-based vascular therapies. The transplantation of iPSCs elicits robust allogeneic immune responses mediated by T cells, Natural killer (NK) cells, and complement, although recent hypoimmune engineering strategies have demonstrated prolonged survival and functional integration in immunocompetent hosts, indicating substantial progress in overcoming rejection[199]. iPSC-derived vascular cells exhibit variable immunogenicity. While generally less immunostimulatory than primary cells, their surface antigen expression and cytokine profiles can still trigger immune recognition, requiring rigorous evaluation and potential immune-evasive modifications[200,201]. MSC therapy, once considered immune-privileged, has also been associated with donor-specific antibody formation and cellular immune activation in certain contexts, especially after repeated or mismatched administration[202].

MSCs from different sources, such as UCMSC and ADMSC, exhibit differences in anti-apoptosis, angiogenesis and other aspects. Currently, stem cell therapy has not been fully combined with the concept of "precision medicine" for individualized design, which may lead to inconsistent therapeutic outcomes[121].